Russia gives Spain digital copy of a valuable medieval manuscript stolen in 1835

The 11th-century ‘Will of Count Gundesindo’ disappeared from a monastery and showed up over a century later in Saint Petersburg

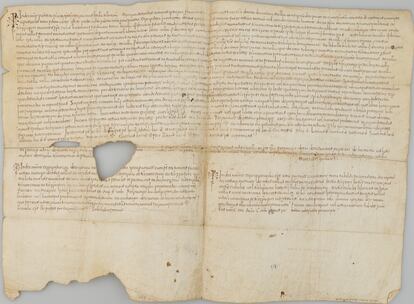

In 1835, the monastery of San Salvador de Oña, in Spain’s northern province of Burgos, was targeted by the Spanish Confiscation, a lengthy process in which the state forcibly seized property from the Catholic Church and municipalities. The monastery’s community of Benedictine monks was expelled; the magnificent Gothic building founded in 1011 by Count Sancho García of Castilla was abandoned; its spectacular medieval library was completely looted. Manuscripts and books made their way to all corners of the world, where collectors treasured them. That was also the case of the so-called Will of Count Gundesindo or Parchment of Fístoles, a document with Visigothic handwriting dating back to the 11th century, which ended up on the shelves of the Scientific and Historical Archive of Saint Petersburg’s Institute of History, in Russia.

Now, thanks to the researchers Máximo Gutiérrez and Iván Gastañaga, a 3D digital copy will be kept in the Historical Archive of Cantabria, in northern Spain. The valuable document chronicles part of the early medieval history of the north of Burgos and Cantabria, and until now the only evidence of its existence had been more or less inaccurate copies and transcriptions.

The power of the monasteries in the 11th century was immense. The legal texts in their custody registered their ownership over churches, fields and even entire towns. It is a fact of record that any mistake in the drafting of a document, whether intentional or not, could change the rights over an asset or an inheritance. For this reason, the will of Count Gundesindo included the original copies of three other testaments from the years 811, 816 and 820 that certified the properties and rights of his family. These were lost, but not the parchment, which was kept in the monastery. As Gutiérrez explains: “The will is of great importance for paleography and for understanding the Spanish Middle Ages. After its disappearance in 1835, only a few transcriptions could be consulted, many of them containing errors or personal comments by the transcribers.”

Between 1835 and 1866, the year the National Historical Archive was created, Spanish heritage suffered its second great period of looting following the Peninsular War fought against Napoleon in the Iberian Peninsula. Thousands of documents of incalculable value were destroyed, taken out of the country or added to private collections. The Will of Count Gundesindo was among them, but fortunately it suffered a better fate than a 9th-century Bible, also taken from the Oña monastery, whose pages were burned by a local notary to “roast sausages.”

After successive state expropriations that resulted in the abandonment of numerous Spanish monasteries and churches, the centuries-old documents they contained were mainly bought by French and German dealers, who resold them to major European and North American collectors. And so it was with the medieval Will of Count Gundesindo, which ended up in the hands of a Russian bibliographer named Nicolai Petrovich Lijachiev, who had acquired it on one of his regular summer trips to Europe. Nothing more was heard about it.

It was not until 1982 when Emilio Sáez, a professor of medieval history, found it in the archives of the Saint Petersburg Institute of History, thanks to his contacts with academics from Eastern Europe. Sáez discovered that the Russian institution had “a Spanish documentation fund” of which there was no record in Spain, with texts dating from the 11th century to the 19th century, and including manuscripts by the kings Ferdinand IV and Alfonso XI, as well as letters written by various queens. There were 463 documents in total. The professor transcribed some of them, including the one he considered the most important, the count’s will, since Soviet authorities would not let him make a copy.

In 1988, the scholar died in a car accident, so it was his son Carlos who completed and published a book with everything that the researcher had managed to collect from the documents kept in the then-USSR. Gutiérrez and Gastañaga decided to take up Sáez’s work where he’d left off, given that technology had advanced remarkably in recent decades. A year ago, after some complicated negotiations, these researchers managed to get Russian authorities to make a digital copy of the document, which on Wednesday was officially delivered to the archive in the northern Spanish region of Cantabria. “It is of enormous symbolic value,” says Gutiérrez, “because it reminds us that we were not capable of defending our own heritage. But it also has its positive side, because thanks to people who did appreciate it, it still exists, even if it is in a foreign country.”

Lijachiev, for his part, created his own museum at home with everything he had bought in the late 19th century in Europe’s main capitals. With the October Revolution, his precious library was nationalized, and even though he was appointed its director, in the 1930s he was purged and sent to Siberia. He died in 1936 and to this day he remains a reference in the world of academia.

“Of the fabulous library of Oña, only a tiny fraction has been saved. Even the Libro de la Regla, which did enter the National Historical Archive, was lost in 1936 during the Civil War, according to Sáez,” notes Gutiérrez. “The second half of the 19th century was a harrowing time for [Spain’s] national heritage. The looting tradition began, and many high-placed people were involved. Powerful people who did not see any problem with everything leaving the country as long as it meant good business.”

Emilio Sáez, whose biography has been included in the Royal Academy of History’s list of important figures, achieved national and international recognition and participated in numerous conferences and scientific meetings around the world. Today, the cultural center in Caravaca de la Cruz bears his name as a tribute to his scholarly work. No one remembers the name of the person who stole the priceless book from a monastery in Burgos.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.