The medieval Spanish monastery snapped up by William Randolph Hearst

A historian reconstructs how Santa María de Óvila was dismantled, shipped to the US to be incorporated into the newspaper baron’s California mansion, but finally forgotten in a San Francisco pier

When it came to the sale of the monastery of Santa María de Óvila in Trillo, in the Spanish province of Guadalajara, the Count of Romanones looked the other way. The early 20th-century politician and entrepreneur was a powerful man – he served as mayor of Madrid, speaker of both houses of parliament, and was prime minister on three occasions – but he made no move to save the monument despite pleas from historians and journalists.

And so the Cistercian monastery, located about 137 kilometers by road from Madrid, was disassembled in 1931 in preparation for its passage to the US where newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst, the man who inspired Orson Welles’ classic movie Citizen Kane, planned to incorporate it into his Wyntoon estate in northern California.

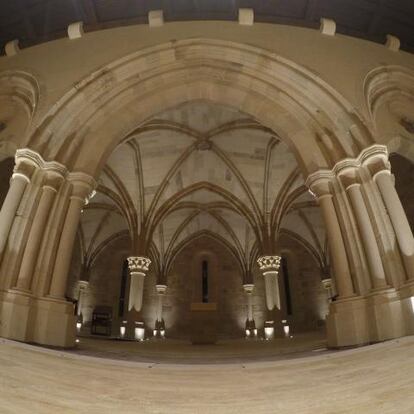

Built in 1175, only the foundations of the church and of a Renaissance cloister survive, as well as large bare walls, inside which farm machinery and all-terrain vehicles are stored. But its heart – the chapter house, the refectory, the monks’ sleeping quarters and its ornate portal – has been part of New Clairvaux Abbey, located 300 kilometers north of San Francisco, since 2008. It was donated by the San Francisco City Council after being confined to crates on a San Francisco pier in 1941.

The historian José Miguel Lorenzo Arribas has penned Óvila (Guadalajara) 90 years after its sale, published by the Cervantes Institute. “That’s why I object so strongly to Romanones,” he jokes.

The origins of the monastery lie in King Alfonso VIII of Castile’s desire to consolidate his power in the center of the peninsula after taking it from Moorish forces. In 1175 he ordered the construction of Santa María de Óvila in what is now the municipality of Trillo. Arribas describes the dismantled church as being shaped like a Latin cross with three apses. The interior featured ribbed vaults and was presided by a richly decorated Mannerist-style portal. The cloister adjoining the church was covered with pointed ribbed vaulting with double arches.

This impressive monument was erected in a fertile valley on the banks of the Tagus, surrounded by dense forests. It was the cultural and economic center of the area until the 15th century, when civil wars caused a gradual exodus. In the 18th century, the monastery lost its entire library in a massive fire, although its definitive decline did not begin until 1835 with the Spanish Confiscation, when the government seized and sold Catholic Church property.

In 1928, the ever-needy Spanish state sold the monastery for 30,000 pesetas (€180,300) to Fernando Beloso, director of the Spanish Credit Bank, an important landowner in the region of Alcarria. In 1931, he resold it for an unknown amount to media tycoon William Randolph Hearst. Hearst’s intention was to reassemble it in his Californian mansion in Wyntoon along with other pieces he had acquired from all over the world. But things did not turn out as expected, his plans changed and the centuries-old Spanish masonry ended up in piles on a pier in San Francisco where it suffered numerous acts of vandalism.

In 1932 the historian Francisco Layna Serrano published The Óvila Monastery, in which he denounced what had happened and described how he tried to stop the sale. “I objected angrily to the plundering, addressing a somewhat violent letter to the Count of Romanones, decrying the fact and encouraging him to prevent the expatriation of the Óvila monastery, since he was the best person to prevent it and to seek a sanction for the selfish seller [meaning Beloso], since, in addition to being an arrogant politician from Alcarria, he was a minister, director of the Academy of San Fernando and author of a law defending the national artistic heritage.” The count of Romanones, however, completely ignored him, according to José Miguel Lorenzo.

Lorenzo also recalls that Miguel España, a journalist from the national newspaper Abc, was among those who spoke out against the sale in 1931 in his article How an American is taking the monastery of Santa María de Óvila to his country. “Each piece was carefully wrapped in a bundle, and marked with a number and a letter, G or R, which were to indicate whether they were Gothic or Romanesque, two predominant architectural styles,” wrote España.

To reach the old monastery, it was necessary to cross the Tagus River by boat. But Hearst improved access by opening a road with a wooden bridge and laying tracks for mining wagons. The blocks of stone were loaded onto trucks and transported to Madrid. They were then taken to the coast and shipped to the US to be stored in the Golden Gate Park warehouse in the port of San Francisco. In 1941, the year Citizen Kane was released, Hearst sold the disassembled monastery to the city for $25,000, and it remained on the pier until 2000.

That year, the Benedictine monks from New Clairvaux Abbey in California discovered it. Recognizing it would make the perfect addition to their large monastic complex in Vina, they collected donations, and in 2013, with the advice of José Miguel Merino de Cáceres, a professor of history of architecture at the Polytechnic University of Madrid, they were able to resurrect it.

Meanwhile, in Trillo, only a small road sign on a roundabout points the way to the remains of the monastery. Set against the backdrop of a nuclear power plant, it belongs to a private estate. A worn information board by the monastery’s walls states that “only one year after this irreparable damage was done, on June 3, 1931, the Government of the Republic declared the ruins of Óvila a National Historic Monument.” By then, of course, “the church, the refectory, the chapter house, the novices’ dormitory and part of the cloister” had all gone.

The current owners do not allow public access to the site, stating, “We are not interested in talking about it. It is private property.”

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.