From sculpture to installation: The new dimensions of the photobook

Photographers test the limits of visual narrative through creations that transcend definition, adopting different resources and formats

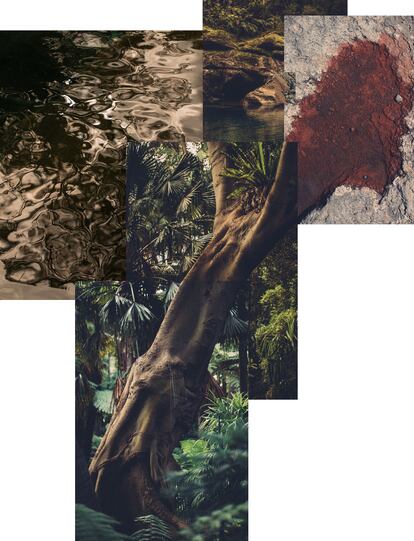

What would happen if a group of humans, fleeing from the climate catastrophe, moved to another planet and found a majestic, virgin and pristine landscape? What would they do? How would they colonize that habitat? Would they have learned from their mistakes, or would their predatory instincts surface again? These were the questions that British photographer Gareth Phillips pondered while visiting the remote South Island of New Zealand. There, experimenting with a macro lens under the exuberance of one of the few remaining wild territories, the author created Caligo, a fictitious alien Eden that took the form of a book-sculpture.

Initially, the installation was shaped like a vertically suspended seven-meter accordion book (a format known as leporello). From there, the author experimented until he reached the horizontal format that earned him a recognition at the Aesthetica Art Prize 2023. The work is exhibited at the York Art Gallery in London, along with that of the 20 other winners. Measuring 295 centimeters (9.7 feet) wide and 460 centimeters (15 feet) high, and made up of five pages created with 33 images and a text, this imaginative response to the serious and unstoppable environmental deterioration that permeates our present and marks our future is presented as an autonomous work of art that can be seen as an object, a sculpture or an installation.

The photographer, who currently alternates between living in Spain and the United Kingdom, aims to create something that stands out within the saturated photobook market; a book that goes beyond the established parameters to redefine the limits set by the industry. The project will also have a print run of 20 small, handmade photobooks.

“The photobook as an object, sculpture, or installation, is a relatively new entity,” Phillips notes. “Of course, others have experimented and created books as objects, and I am very inspired by the path they have already traveled. But the possibilities to challenge and broaden the perceived interpretations through this format fascinate me.”

Despite having spent 15 years doing documentary photography, the artist does not hesitate to resort to fiction for his personal projects. “I couldn’t accept restrictions when creating, which is why I want to think outside the box and not be limited by labels,” he adds. “Fiction can be a very useful and interesting tool, especially at a time when we are continually forced to question the truth in different ways. It will play a very important role in reaching the public, as is already happening with the use of artificial intelligence. It could be argued that documentary photography is also fiction, in the sense that photography may not always serve the truth.”

“Caligo has to do with the idea of colonizing a new planet and with climate change, but it’s also a celebration of our landscape,” Phillips notes. “In any case, all that is destined to remain of Earth is the record of what it once was, and this is my contribution to that archive.”

Exploring the limits of visual narrative

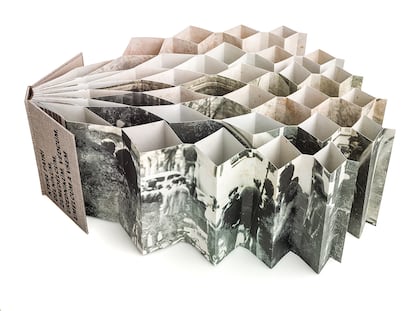

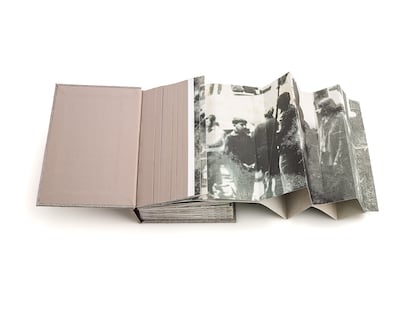

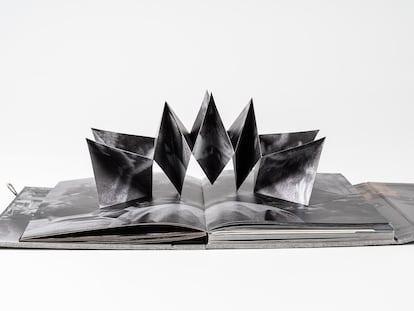

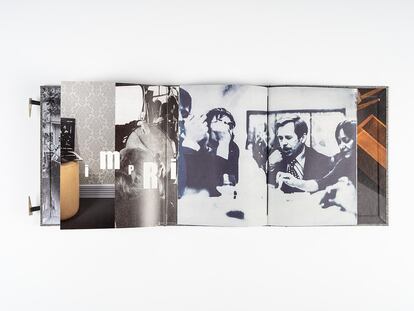

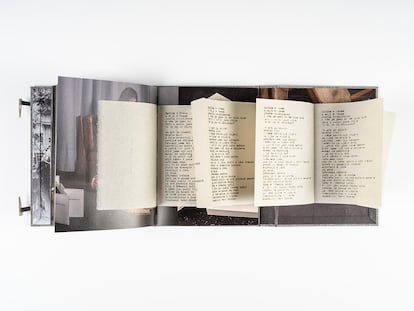

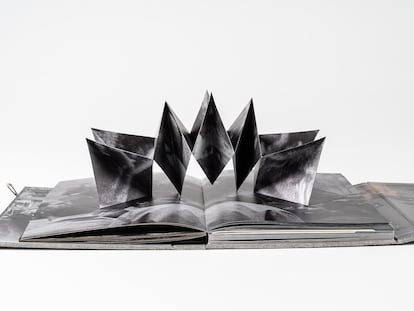

The photobook-sculpture phenomenon has also gained strength in Spain in recent times. One noteworthy example is Two Thousand Words, by Roberto Aguirrezabala, a publication about the peaceful resistance of the period known as the Prague Spring; through a page-folding technique, the book becomes a sculpture that extends almost seven times its size. This work was a finalist in the Author’s Book category at the Arles Meetings photography festival in 2021. The creator repeated his candidacy the following year with Samizdat, an artist’s book that, even if it does not fit within the definition of sculpture, stands out for the variety of resources it offers the reader through the incorporation of different designs, types of paper, fonts and narrative styles. It is a reflection on the clandestine actions carried out in Eastern Europe to avoid the editorial censorship imposed during the Soviet hegemony. The publication was also a finalist in the latest edition of the Lucie Photobook Price.

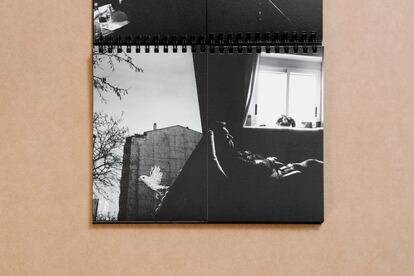

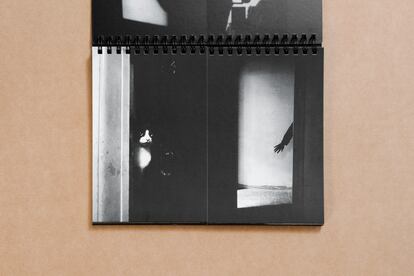

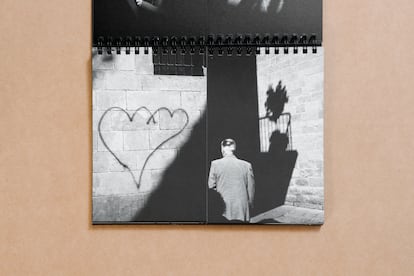

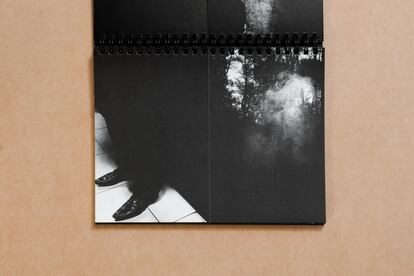

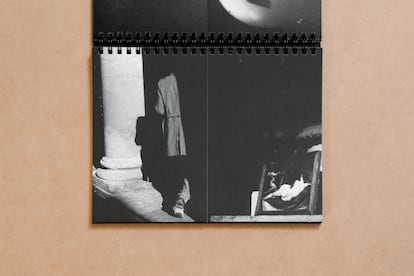

“A drop + a drop is not two drops, it is a bigger drop that is talking about the sea,” writes David Salcedo before introducing the reader to the dark illusion that is +, a work in which the author explores the limits of visual narrative to offer the reader a set of images, previously unconnected, which generate different interpretations through different combinations while redefining the space in which the action unfolds through interaction with the reader.

The author’s intent has always been to deceive the eye and baffle the viewer. In 2012 he began to work with a series of black and white diptychs, which he combined in different ways; some images captured in the streets, with others filled with intimate connotations for the author. In 2015, Salcedo won the FNAC New Talent award with this project. Still, it would take him seven more years to come up with the right form of photobook to accommodate this complex puzzle. “It is a living book,” he claims. “My intention was that every time a reader returned to the book, they would find different meanings.” Thus, the two groups of 33 photographs that make up the piece give rise to multiple compositions arranged in diptychs, triptychs or quadriptychs. Drop by drop, Salcedo offers a sea of images over a black background, a space to navigate through chance and mystery.

‘Caligo’. Gareth Phillips. Aesthetica Art Prize 2023. York Art Gallery. London. Until June 2.

‘Two Thousand Words’. Roberto Aguirrezbala. Self-published.

‘Samizat’. Roberto Aguirrezbala. Self-published.

‘+’. David Salcedo. Possible Editions. 132 pages. 35 euro.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.