The trailblazing ‘Krazy Kat’ who changed the course of comics

George Herriman’s cartoon revolutionized the genre and influenced Walt Disney, Jack Kerouac, Art Spiegelman and even pioneered the word ‘jazz’

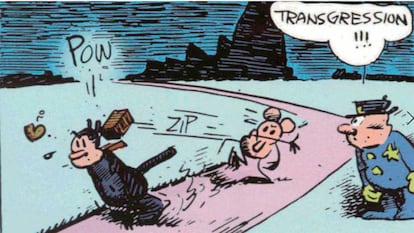

In 1913, Krazy Kat appeared to change the course of comic history. For the next 31 years, the cartoon strip published in the New York Evening Journal newspaper depicted the stormy relationship between a carefree, gender-switching cat named Krazy and a perpetually angry mouse named Ignatz. The mouse despised Krazy and wasted no opportunity to throw bricks at his crime partner’s head. True to his romantic nature, Krazy interpreted these brick lobs as gestures of affection. This seemingly inane relationship masked an ironic undertone about the issues facing American society in those days. In 1924, critic Gilbert Seldes called the Krazy Kat cartoon strip “the funniest, most fantastic and satisfying work of art produced in America today.” Years later, The Comics Journal, a prestigious American trade magazine, chose Krazy Kat as the best comic of the 20th century.

Krazy Kat creator George Herriman was the enigmatic son of mixed-race parents who grew up in Los Angeles in the late 1800s. One of the first creators to publish his work as a newspaper comic strip, the new venture was immediately successful and helped drive newspaper sales in the early 20th century. Herriman’s strips soon became popular for their blunt, irreverent tone. “He invented a new language,” said Michael Tisserand, the author of Krazy: George Herriman, A Life in Black and White (Harper Collins, 2016), a critically praised biography of the cartoonist.

My interview with Michael Tisserand takes place in a café in New Orleans’ colorful Tremé neighborhood, where George Herriman was born and lived until he was 10. Finding it was easy — everyone knows everyone in the city’s cultural circles. Tisserand is a professor at the University of Minnesota who makes frequent trips to New Orleans, where he once lived. He maintains strong bonds with the city and even has his own Mardi Gras parade troupe. Tisserand often writes about New Orleans: The Kingdom of Zydeco is about the musical genre that evolved in southwest Louisiana among French Creole speakers; and Sugarcane Academy is about how a New Orleans teacher and his students created a new school in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

Michael Tisserand is an affable Krazy Kat fan who smiles a lot. The café where we talked over coffee is very close to where Herriman was born. “His work is better understood in the context of his childhood in Tremé before his family moved to Los Angeles,” said Tisserand. The first African-American neighborhood in the United States left an indelible impression on the Krazy Kat creator, who grew up in a mixed-race Creole family. The cartoon captured the atmosphere of the times when oppressive racism and segregation stifled non-white communities. “You can’t explain his work, his use of color, even his views on issues like race and gender, without considering his Tremé origins.”

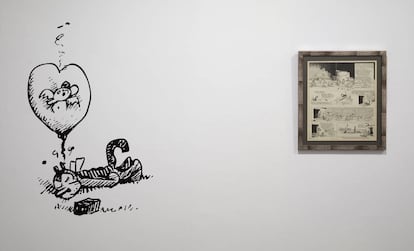

In October 2017, the Reina Sofia National Art Museum in Madrid exhibited Herriman’s work, including Krazy Kat, of course. The exhibit often referred to Tisserand’s biography of Herriman, which has become an indispensable source about an influential comic creator. Herriman’s artistry and dialogue captivated some of the best cartoonists of the 20th century, including Elzie C. Segar (Popeye), the renowned Walt Disney, counterculture legend Robert Crumb, and Art Spiegelman, the acclaimed creator of Maus.

“Herriman is truly the godfather of the modern graphic novel. Spiegelman often mentions his debt to Krazy Kat, just like Bill Watterson, the creator of Calvin and Hobbes,” said Tisserand. But Herriman’s work also inspired writers like Amiri Baraka, Langston Hughes and Jack Kerouac. Sipping his coffee, Tisserand says there are two crucial elements to understanding Krazy Kat. “George Herriman was very active in social issues that remain relevant today. His ancestors were not slaves, but his Creole (an ethnic group of Louisiana French, West African, Spanish and Native American origin) family did not have the same civil rights as white people. In that context, his use of black and white and color in the comic strips, and the sexual ambiguity of his characters are loaded with meaning.” The sexual tension between Krazy and Ignatz is heightened by a third protagonist — Offisa Pupp — a dog and police officer who tries to protect Krazy from Ignatz’s bricks. A strange love triangle evolves.

Tisserand’s smile gets wider when our conversation turns to music. His book, The Kingdom of Zydeco, has become a reference text for fans of a musical genre little known outside Louisiana. “It stands at a crossroads between Cajun music, rhythm and blues, blues, rock, rap, gospel, swamp pop and country... all melded through an accordion. It’s a blend of traditional music played for generations with the latest popular sounds. It’s always been like that — it defines this culture’s uniqueness generation after generation,” said Tisserand. “It’s a sound that encourages people to dig deep into life’s problems and produce the most joyful music you can imagine. It has roots in West Africa, the Caribbean and the traditions of indigenous peoples. It’s a shining star in Louisiana’s musical greatness.”

Talking about the famous New Orleans jazz, Tisserand harkens back to Herriman’s comics. “One of the first times the word ‘jazz’ appeared in newspapers is in Krazy Kat. It was a sound effect when one of the Ignatz’s bricks hits Krazy’s head. When the comic strip was adapted for the theater in 1922 by John Carpenter, the show was named Krazy Kat: A Jazz Pantomime.” Tisserand last words before we leave the café: “George Herriman was related to Jelly Roll Morton [a pioneer of New Orleans jazz], and in a self-portrait he sits at his drafting table with a radio playing in the background. Music was everywhere in his work!”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.