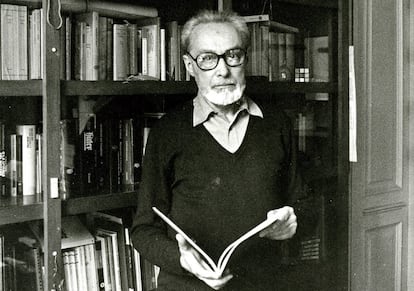

Primo Levi, a suicide wrapped in shadows

The Italian writer Ferdinando Camon, who has published his conversations with the author of ‘Survival in Auschwitz,’ believes his death may have been accidental, contrary to the official version of events

From time to time one should listen to George Tabori and take the Holocaust with some degree of humor. The Hungarian theater director used to cite the polite deference his own father showed to a fellow prisoner outside the Auschwitz gas chamber: “After you, Mr. Mandelbaum.” Tabori, who worked in Hollywood, would understand it if we found a reasonable resemblance between Quentin Tarantino’s films and Primo Levi. In films like Inglourious Basterds and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Tarantino used uchronia — a fictional time period — to rewrite the stories of Nazi Germany and the Manson family with a happy ending. There is no uchronic fiction in the life of Primo Levi, but it would sometimes seem so: Auschwitz, the industrial-scale extermination camp for people, not only did not kill him, but saved his life on two occasions. His survival meant the Nazis were letting escape their greatest enemy, a Jew who was a brilliant writer and who would go on to build a monument against oblivion.

The first time was in the Aosta Valley. Levi had joined the partisans fighting German-occupied areas of Italy without even knowing how to load a rifle. The fascist militias captured him in a punitive action and sentenced him to death. He confessed to being a Jew, and was instead put on a cattle train to Auschwitz. He had the number 174517 tattooed on his forearm and survived 11 months as slave labor in the satellite camp of Monowitz. The second time was at the end of the war, when the Red Army was approaching and the SS evacuated the lager in the dead of winter. He was not part of the death marches because he was sick with scarlet fever and quarantined in his barracks. His biographers even point to a third reason: Levi suffered episodes of clinical depression, and his condition as a witness to Nazi barbarity was a vital stimulus that saved him until the end.

If we accept that what happened on the morning of April 11, 1987 was a suicide, the happy ending of Tarantino’s non-uchrony is broken. It is difficult to avoid feeling that Levi was a delayed victim of Nazism, that any trauma can be overcome except that of Auschwitz, sewn on his self 40 years later like the Star of David. That day, at 10:05 a.m., Levi opened the door of his home in Turin, walked down the landing, hugged the railing, and fell from a third-story stairwell. The impact on the marble floor killed him instantly.

The police report certified the suicide. But the Italian writer Ferdinando Camon has always held that it was an accidental death. In his book Conversazione con Primo Levi: Se c’è Auschwitz, può esserci Dio? (or Conversations with Primo Levi: If there is Auschwitz, can there be a God?, recently also published in Spanish) Camon went over his last conversations with Levi and included an introduction penned in 2014 in which he explains that the author of If this is a man (better known in the US by the title Survival in Auschwitz) sent him a letter shortly before he died — it arrived on April 14 — full of projects and expectations (“send me the Libération article as soon as it comes out, find out if Gallimard wants more copies of my books”).

Speaking recently inside his home in Padua, the 87-year-old Camon, a Strega Award winner for his fictional memoir Survival, no longer seemed so sure: “I have my doubts, the suicide explanation does not convince me. If he jumped, he did not do it of his own free will, but because he had a void inside.” Then Camon added: “Those who committed suicide in the camps died because life was hell, and death was better than life. If Levi committed suicide, it was because of this. The problem is that for Levi the lager was the past… But maybe it wasn’t really the past. Maybe the lager never passes.”

Philip Roth also found Levi very cheerful and vital in September 1986 when he visited him in Turin. And the Spanish writer Adolfo García Ortega reconstructed Levi’s last hours in his 2002 novel El comprador de aniversarios (or The anniversary buyer). There is a memorable character in the book, the boy Hurbinek, who died in Auschwitz at the age of three and who is based on a mention made by Primo Levi in The Reawakening. “Camon’s theory is not credible, beyond that minimal doubt about who commits suicide in a stairwell,” says García Ortega. “Levi, with his successful past and present as a writer, faced Holocaust survivor syndrome, a mix of depression, guilt, and meaninglessness. We know its effect because several writers faced this self-destructive syndrome and chose to end their lives. I now remember Paul Celan and Jean Améry. Suicide was a cry or a personal denunciation that we have to interpret as heroically human.”

Paul Celan lost his parents in a Transnistria death camp. The Romanian poet, author of Todesfuge (Deathfugue), a canonical poem about the Holocaust, threw himself into the Seine in 1970. Jean Améry warned in advance and published On Suicide: A Discourse on Voluntary Death. His biographer Irène Heidelberger-Leonard recounts that a student, perhaps one of the Kantian tradition, asked him why he had written that book and had not committed suicide. Améry replied: “A little patience!” The Austrian writer and Levi lived together in Auschwitz without knowing it. Both died at the age of 67. Améry killed himself in 1978, in a suite at the Österreichischer Hof hotel in Salzburg, after ingesting a first-aid kit full of barbiturates.

Levi didn’t leave any notes, just the shopping list, but suicidal people don’t leave farewell letters. His admirers have speculated like sentimental forensics about the indiscretion of his chosen method, in the most visible and painful place for his family, on a landing where the intimate and the public converged in his house on Corso Re Umberto, where he was born and always lived. As an experienced chemist, he could have opted for chemistry.

The Spanish author Antonio Muñoz Molina has been to Corso Re Umberto street, looking for number 75. The author of Sepharad and the foreword to Levi’s Auschwitz Trilogy says: “It would seem like an act somewhere between arrogance and irresponsibility to load the possible suicide of Primo Levi with excessive (and negative) meaning. How can we judge someone who has suffered infinitely more than us? For me, the fact that Levi committed suicide, which as we know is not an entirely certain fact, would not invalidate either his struggle, which he conducted alone for so long, to bear witness to the horror, or his vindication of rationality and goodness in the face of barbarity.” Muñoz Molina also recalls that, when reading Levi’s The Drowned and the Saved, there was “an abysmal note of bitterness and weariness, even a terrible call from the darkness at the end, when the voice of the kapo continues to ring in dreams.”

For the biographer Ian Thompson, who does not doubt it was suicide, citing Auschwitz as a trigger for his untimely death is a romantic convention. He discards the writer-Jewish-survivor pattern that ends in suicide after a lifetime devoted to work about the Nazi camps. It wasn’t Auschwitz that killed him, it was depression, he believes. And many factors played a role, from Levi’s own genetics to his past, his panic about becoming senile and his mother’s illness.

The transcendence of Levi’s death elevated his status as a writer. Camon lashes out at the big publishing houses that refused to print his work until that day, especially the prestigious French house Gallimard. Camon had tried to get Levi’s books accepted. After April 11, the laconic rejection (“Ferdinando, we just don’t like it”) turned into a desperate howl (“Ferdinando, please convey this message to Mrs. Lucia [Levi’s widow] and to the Einaudi publishing house: Gallimard is willing to purchase all of Levi’s books that are available”).

“Auschwitz exists, so God cannot exist,” Levi told Camon. And he made a note in pencil in the final review of the book: “I can’t find a solution to the dilemma. I look for it, but I cannot find it.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.