Rave culture: More than just drugs and music

Beyond the famous New Year’s Eve parties and the stories and controversies that surround them, Europe’s ‘free party’ movement has an ethics and a history that traces back to its origins in the 1980s

A group of friends and fellow partiers sets up a massive sound system somewhere far from civilization — a forest, a field, a bridge, an empty warehouse, a tunnel, an abandoned monastery. They don’t want to bother anyone and they don’t want anyone to bother them. Through word of mouth, tens, hundreds or even thousands of partiers converge on the spot, with no promotion, no licenses, no admission fee, no time limit, and no restraints. There is electronic music, an abundance and variety of drugs, endless dancing. It’s a “free party,” in every sense of the word “free.” It’s a rave, meaning: “to show signs of madness and delirium.”

Every year, like tradition, an illegal New Year’s Eve festival that goes on for days without end captures the attention of the media, inspiring a combination of curiosity, hilarity and indignation. This year, that party was in the Spanish town of La Peza, Granada. There, in addition to the surprise gathering of around 4,000 ravers over the course of five days, which included a caravan of some 200 vans and small trucks, the main story (and the subject of much levity on social media) was the reception the partygoers received by the town’s residents, who came out in droves to witness the party and meet the ravers, and were by and large delighted by what they found — so much so that they invited them to come back the next year. “There is respect here,” said Paquita la Ravera, a thirty-something raver from Torre del Mar, Malaga, who attended the party. “No matter what resources you have, you can come, because it’s open and it’s free. I have a right to go to a rave, have fun, and not have to pay 50 euros to dance in a room while other people look down on and judge me.”

“Rave is more than music + drugs; it’s a matrix of lifestyle, ritualized behavior and beliefs,” writes British music journalist Simon Reynolds in his book Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture (Faber & Faber, 1998). “To the participant, it feels like a religion; from the standpoint of the mainstream observer, it looks more like a sinister cult.” Beyond the sensational stories and controversies surrounding the phenomenon, rave culture has a history and a set of values that, given its underground character, remain relatively unknown to the outside world.

Rave values

“It’s a movement that unites people of all ages who appreciate living and feeling,” says Anais MFS, a 25-year-old French raver who attends parties once or twice a month. “Rave allows us to be the person we really are, without judgement. There’s a spirit of solidarity and unity. To be part of this movement is to be part of a family.” The main values of the movement are summarized by its cardinal slogan: “PLUR,” an acronym for Peace, Love, Unity, Respect. “We see this, for example, in the role played by women,” says Fermín Fernández Calderón, a psychologist at the University of Huelva in Spain, and the author of a major study on rave culture. “These are environments where, in general, women are respected and not objectified. The media usually associate drug use with bad behavior, but at raves, violence is discouraged and is actually quite rare.”

No one hides the fact that drugs are a central feature of the free party experience, which most participants would likely find ridiculous in a state of sobriety. Some of the most popular drugs include ecstasy (a substance central to dance and rave culture, which encourages uninhibited movement and sensuality), cannabis, and to a lesser extent, amphetamines, tobacco and LSD. Alcohol and cocaine are also used, but less than in other party scenes, such as one might find at a bar, a music festival, or a nightclub. According to Fernández Calderón, even though raves tend to have high levels of drug consumption, there is also a culture of awareness and safety regarding drug use: participants take test doses to avoid harm, share knowledge of different risk prevention strategies, and generally know how to help people who suffer overdoses or other harmful experiences. “Getting excessively drunk, on alcohol, for example, is generally frowned upon,” Fernández Calderón says. Despite these measures, tragedies do still sometimes happen: in 2011, for example, two 18-year-olds died after consuming the hallucinogen Datura stramonium at a rave in Madrid. And this past summer, a 32-year-old Swiss woman died at a 3,000-person rave in Salce, Zamora, Spain, though the cause of death was determined to be a pre-existing heart condition.

The genealogy of ‘free parties’

Like any underground scene or movement, the history of “free parties” in Europe is a bit fuzzy. We know, however, that it began in the UK in the late eighties. Some say it was inspired by the party scene in Ibiza, Spain; others that it was brought by hippies coming from the United States. A more political history of raves draws connections to the situationists, or the Temporarily Autonomous Zones theorized by anarchist Hakim Bey. And, of course, some see it as an evolution of ancestral shamanic rituals.

In the late 1980s, the UK experienced its so-called Second Summer of Love (the first having taken place during the heyday of the hippies in 1967), which saw the rise of acid house music and the beginnings of the rave movement. “It was related to the arrival of house and techno music from the United States, which was still very underground, very marginal,” says Spanish music journalist Javier Blánquez, author of Loops: Una historia de la música electronica (Reservoir Books). “In London, with the sudden popularity of acid house parties, the scene exploded, and in a few months a revolution was under way.” Free parties were neither expensive nor exclusive — everyone could participate, emerging DJs could practice their sets, music copyrights were irrelevant, and the parties could go on as long as people wanted. Positivity was central to the movement, and it was decidedly anti-commercial, although some raves, given the potential for profit, eventually ended wound up being legalized or integrating into big summer festivals. Today, it is common to find the word rave used to describe commercial parties and festivals, but the movement’s most principled adherents continue to denounce the commercialization of the term and the perversion of the movement’s original spirit.

It was Spiral Tribe, perhaps the most legendary free party collective, that changed the course of rave history when they organized a week-long party in Castlemorton, England, in 1992, which drew an estimated 20,000 participants, at a minimum. The British government responded by arresting 13 members of Spiral Tribe, claiming that the party had terrorized local residents and had resulted in several people needing psychiatric treatment. Two years later, in 1994, British Parliament passed the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, a law explicitly banning raves. The definition of “rave music” outlined in the law was received with humor and a certain irreverent pride by the movement, defining the genre as any “music that includes sounds characterized totally or predominantly by the emission of constant repetitive rhythms.”

In Italy, the government of Giorgia Meloni has recently begun criminalizing and cracking down on raves and other unauthorized parties, declaring the “invasion of land or buildings for gatherings of more than 50 people” a crime. Many have denounced the law, noting that it will likely be used to criminalize and repress political demonstrations and protests as well. The law was passed as an emergency measure after thousands of young people gathered in October at an abandoned agricultural warehouse in Modena, for a Halloween dance party that was ultimately shut down by the police. “The fun is over,” tweeted far-right minister Matteo Salvini. “They are repressing a cultural movement and a movement for liberation,” said French raver Anais MFS. “I don’t understand why they refuse to legalize a pacifist movement that only creates joy, music and art.”

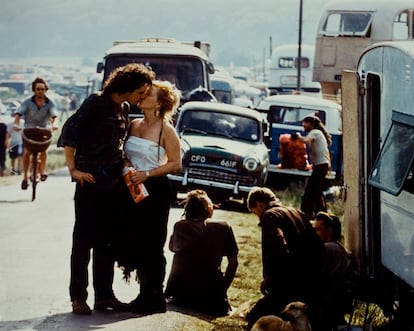

Following the repressive laws in Britain, the free party movement spread like wildfire across the European continent. “Travelers,” including families with children, formed caravans and lived nomadic lives out of trucks and buses, and were generally characterized by their “crusty” style, similar in to the apocalyptic aesthetic of the Mad Max movies. In the nineties, travelers would migrate from place to place, holding “tekno” parties (“free tekno,” or “hardtek,” being the genre of music typical of the subculture) wherever they went, like a mobile circus of electronic and psychonautic music enthusiasts. Some of the more well-known “tribes” of the movement were Spiral Tribe, Kamikaze, Hecate and Desert Storm: each with its own vehicles, name, logo, and powerful sound system. These collectives are also known as “soundsystems,” and in addition to playing loud music, they often project colorful light shows. When multiple soundsystems come together for a party, it’s called a “teknival.”

How to host a rave

In Spain, the rave scene became well-established during the first decade of this century and continues to be a major phenomenon across the country. In Madrid, the most popular party spots are the abandoned monastery of Perales del Río, the Boadilla tunnel, the Matadero de Rivas (an abandoned slaughterhouse in Rivas), and the Cuatro Vientos forest, among others. Raves take place in Catalonia and in eastern Andalusia, where the La Peza rave and the Dragon Festival are held. “There are some spots that are super well-known and people would use to hold raves,” says DJ Carlos Garvi, who was regular presence in the scene. “If two collectives showed up at the same time, they wouldn’t compete, they would simply share the party.” Raves do not have a single, predictable model where everything happens as expected, as might a rock concert or other event, and the content, participants, music, and duration varies from party to party. Spontaneity is part of the movement’s anarchistic spirit.

“For a lot of DJs, those parties were the first opportunity they had to spin for a live audience,” says DJ José Cabrera (who performs as “J.C.”). Cabrera was part of the collective Rave del Túnel (RDT), one of the best-known collectives of the first decade of the century, along with others like Suburban Sound, RDLC and Zapatilla SoundSystem. Raves at the Boadilla tunnel, where he would often spin, could attract anywhere from a few hundred to 3,000 people. All of these parties were organized without any profit motive, though many would face large fines that resulted in some collectives being forced to dissolve.

“We didn’t want to bother anyone, we just wanted to have fun,” Sabrera says. “The police used to surveil and harass us, but once the alarmism of the media died down, they would just see a group of kids having a good time and let us be.” As for the music, each event has its own style, ranging from techno, electro and house, to harder genres like hardtekno or more spiritual ones like psychedelic trance, or other microgenres of electronica like drum & bass or its offshoot, breakcore. Raves tend to encourage other forms of artistic expression and experimentation as well: “Music shaped by and for drug experiences (even bad drug experiences) can go further out because it’s not made with the enduring ‘art’ status or avant-garde cachet as a goal,” writes Simon Reynolds. “Hardcore rave’s dance floor functionalism and druggy hedonism make it more wildly warped than the output of most self-conscious experimentalists.”

Music genre tends to correlate to rave subculture, and the vibe at a given gathering can vary from urban nightclub party to the more “crusty” crowds of punks and hippies. Even in the age of social media, most raves are still advertised through word-of-mouth, to maintain the party’s clandestinity and to avoid detection by authorities. “In the 2000s, we spread the word through text messages, without any kind of flyer or advertising” Cabrera says.

Organizing a rave is no simple feat. Infrastructure and logistics are crucial: you have to find the right place, rent a van and a sound system with good bass, and have a generator (or several). It takes effort, investment and planning. If you run out of gas for the generator, you have to drive to the nearest gas station to get more. “It takes a lot of preparation, because you have to set everything up, do the sound checks... Then you can start in the afternoon and stay all night... or all weekend,” says DJ Carlos Garvi. And then, when it’s all over, the work that no one sees: the clean-up. “It’s important to leave everything better than it was,” Garvi says. Because raves, despite all their peculiarities, share one common downside with every other kind of party in the world: eventually they come to an end.