The amazing story of Toitico, the Cuban police chief exalted in a song nobody believed existed

José Miguel Villa Romero, the son of a humble migrant from Spain, was a law enforcement officer, a Pepsi Cola representative, a prisoner and a chauffeur whose extraordinary life was sung by the famous Trío Matamoros

A small group of friends are gathered at the home of Cuban architect Jose Antonio Choy. He has organized a get-together with music and rum to welcome Spanish editor Begoña Lobo, who has just published a beautiful collection of poems by Cuban singer-songwriter Pedro Luis Ferrer. Begoña is visiting Havana and tells us about the upcoming presentations in Spain of Ferrer’s Poemas sin libro (Poems without a Book), which she plans to publish in book-disc format soon. We all admire Pedro Luis and are glad to hear from him; after begging her for a while, Begoña lets us listen to some songs from La Bunga, his latest album, which has not yet been released. The album includes several songs inspired by the eastern Cuban city of Baracoa, where life is hard. “If you don’t eat coconut, you don’t get full / if you don’t eat coconut, you go crazy,” says one of Pedro’s lyrics. The line makes the group laugh.

Choy was born in the city of Santiago and adores eastern Cuba and its fabulous stories. At one point during the gathering, he turns to one of the guests, Lourdes Villa, and says to the rest of us: “Don’t you know who she is? She’s Toitico’s daughter,” he exclaims.

No one knew about this, so Lourdes begins to tell the story of her father, who was the son of a very humble migrant from the northern Spanish region of Asturias. “My father was born in 1919. He was almost illiterate, so to escape poverty he became a policeman. Because he was very charismatic, hardworking and honest, he was quickly promoted and became the chief of police in Guantánamo, and in 1950 he was made the commander in charge of the city of Santiago, the second largest in the country,” says Lourdes, who is a television programmer. Choy says his parents knew him and told him about Toitico: “He was a very well-respected and beloved man. He cleansed the city of thieves and thugs and had a reputation for being tough but fair; even though he was a policeman, he was not abusive ...”

In Cuba, the word guapo refers to someone given to theft and quick to anger, rather than good-looking. A guapo is a semi-delinquent, someone to be careful around, who likes to fight at the first opportunity and is partial to shouting and stabbing. Guapos readily behave this way, just because they enjoy doing it; that is especially true in eastern Cuba. “But that didn’t happen with Toitico,” says Lourdes. “When my father met a guapo who was spoiling for a fight, he would remove his belt and pistol and fight them one-on-one, not as a policeman.”

Toitico’s real name was José Miguel Villa Romero; he was given the nickname Toitico during his time as Santiago’s chief of police. Nobody knows exactly what the true origin story of the nickname is, but they say that one day he went to raid a brothel and one of the clients came out, protesting: “Hey, I’m the son of a senator.” Another client was a well-known landowner, another guy was related to a priest... He got angry and said: “Toiticos van pa dentro’ [All of you are going in] and it stuck.

“Toitico,” Choy says with a laugh. “Wherever he went, everyone stood at attention. He was so popular that the Trío Matamoros even did a song about him.”

What? Did we hear that right? Noticing the incredulity in the room, Choy gets up and searches YouTube and Spotify. He finally finds the song, a traditional guaracha titled “Toitico” and recorded by the popular musical group in the early 1950s for the RCA Victor record company.

Immediately we put it on, and Cuba’s wonder and genius appears. The song begins with the sound of shouting and a tumultuous quarrel. Then the group begin to sing: “Gentlemen, gentlemen / you have to think / Toitico is coming / and the quarrel ends / and the tantrum ends / and [you] avoid problems.” The melody progresses to one of those old traditional Cuban trova (ballad) choruses and ends with “I don’t believe in guapos / my name is Toitico / in the east there are guapos / Toitico is even more of a guapo.” The song ends as it begins, with the sound of a quarrel among several people; above it all is a voice that orders: “Let’s see, silence, you, you, you, you, that one too, toiticos [all of you], forward march!”

We play the song over and over again; we can’t stop, it’s like a mantra. So we ask Lourdes to tell us the whole story. She says that her mother, Toitico’s widow Magda Soberón Dehesa, is still of sound mind and that we can visit her at home.

Magda lives in a nice apartment in Old Havana. She is 92 years old and enviably lucid. Her smile lights up the room, especially when she talks about her husband. “Once I met him, he never let me go.” Magda, who hails from Guantánamo, was a well-to-do young and beautiful lady when Toitico first met her when she was 18 years old. At first her parents objected, but Toitico had a way with people and won them over. A year later, in 1949, they got married. They had three children: Pepín, a sculptor; Magda, a piano teacher; and Lourdes. She recalls that on March 10, 1952, the same day Fulgencio Batista staged a coup d’état on the eve of an election in Cuba, Toitico resigned as the chief of police. “After turning in his uniform and weapons, he bought a pickup truck and began selling chorizos, hams and other merchandise in Santiago’s bodegas. Since everyone knew him, he did very well.”

But on July 26, 1953, Fidel Castro and a group of young revolutionaries stormed the Moncada Barracks. Toitico was arrested that same day. “Because he had resigned at the time of the coup, they thought he was involved in the insurrection in Santiago, although it was not true,” says Lourdes. On the day of his arrest, Toitico was imprisoned in the same cell as Abel Santamaría, one of the leaders of the Moncada attack. He watched as Abel was taken out of the cell and a soldier stuck a bayonet in his eye before murdering him. Toitico was detained for several months along with those involved in the Moncada attack; he was tried along with Fidel and his group (at the same trial where Castro pronounced his famous “History will absolve me” speech). Ultimately, Toitico was released because he had not been involved in the uprising.

“After that, things got bad; they harassed him a lot, and we moved to Guantánamo,” says Magda. Toitico’s widow smiles again. “He became a Pepsi-Cola representative there… Since everyone loved him, they all bought from him, and in a short time Coca-Cola went under in Guantánamo.” When Fidel Castro’s revolutionaries began their guerrilla campaign in the Sierra Maestra, Toitico was harassed again, and the family decided to leave the country. When the 1959 Cuban Revolution triumphed, they were in Spain. Toitico returned to Cuba immediately. He continued with his Pepsi-Cola business until American companies were nationalized in the 1960s. After that, José Miguel Villa continued to work as a driver in the new revolutionary soft drink company, where he worked until he retired after an illness. His eldest son, Pepín, received a scholarship to study at art schools in Havana. Eventually, the whole family moved to the capital, and Toitico died there in the 1980s.

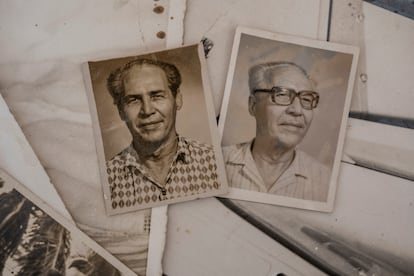

Lourdes and Pepín—who is a respected artist in Cuba and famous for his bronze sculptures that adorn various public spaces in Havana, like the one of John Lennon in a park in El Vedado—says that their father always told them that he was a friend of the Trío Matamoros and that they made a song for him, but no one in the family believed it. “We thought they were his fantasies, but three years ago Choy found the song by chance and called us,” says Lizzie, Toitico’s granddaughter and the owner of a small restaurant in Havana. That day the whole family and the architect had a party at her restaurant.

Lourdes gets emotional when she remembers her father. “In the midst of the Special Period crisis, in the 1990s, I had to go to Guantánamo for work, and I went to stay at the Martí Hotel. It was summertime, and it was very hot. The receptionist was an older man and he told me that there were no rooms available with air conditioning, just fans. When he asked for my personal information and last name, the man was surprised, he told me that in the city there had been a famous police chief who had the same last name, Villa. When I told him that he was my dad, a room with air conditioning became available immediately,” she recalls. Then she sighs and says that she hopes Toitico’s story will be known one day.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.