Changes to Roald Dahl’s stories trigger global outrage and doubts about their legality

Puffin Books and The Roald Dahl Story Company made hundreds of edits in the latest editions to the dismay of loyal readers, famous writers like Salman Rushdie and even British Premier Rishi Sunak

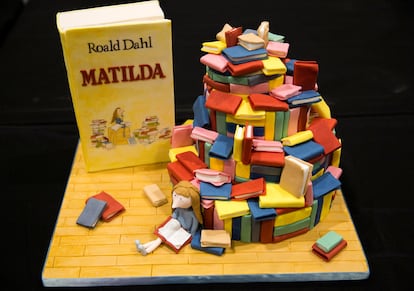

Changes to Roald Dahl’s original texts, made by his publisher and the entity that manages his legacy, in pursuit of more inclusion, have aroused global outrage. Salman Rushdie’s tweet sums it up: “Roald Dahl was no angel, but this is absurd censorship.” Thousands of complaints from readers have flooded social media sites and opinion columns. Even British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak jumped into the fray and highlighted, through a spokesman, the importance of ensuring literature is “preserved and not airbrushed.” Hundreds of modifications were made to passages referring to weight, gender, mental health, violence and race. The attempt to placate sensibilities affects the author’s most famous novels, Matilda, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and The Witches. Dahl had no say in the matter since he died in 1990.

The posthumous editing of Dahl’s work is one of the reasons why some experts doubt its legality. It would not be allowed in Spain, as its Intellectual Property Law protects the integrity of such work. Lawyers consulted by EL PAÍS say that the Spanish government has the authority to guarantee the preservation of the original work if it were in danger of disappearing.

The Cloud Men in James and the Giant Peach are no longer men. They’re Cloud People, per the new edits to the text. The little foxes in Fantastic Mr Fox are now females. A mention of Rudyard Kipling in Matilda has been changed to Jane Austen. These are some of the changes in the latest editions of Roald Dahl’s children’s stories published by Puffin Books with the blessing of The Roald Dahl Story Company (RDSC). This organization manages the copyrights and trademarks of author Roald Dahl and was acquired in 2021 by Netflix. There are no longer “fat” or “ugly” people in Dahl’s novels. British newspaper The Daily Telegraph broke the story and quoted the discreet notice at the bottom of the copyright page of Puffin’s latest editions of Dahl’s books: “Words matter. The wonderful words of Roald Dahl can transport you to different worlds and introduce you to the most marvelous characters. This book was written many years ago, so we regularly review the language to ensure that it can continue to be enjoyed by all today.” When EL PAÍS contacted Netflix, they referred the request to the publisher since the changes were made before the acquisition.

In Spain, the children and youth division of the Alfaguara publishing house has the Spanish-language rights to Roald Dahl’s books and publishes them throughout Spanish-speaking countries. Sources at Alfaguara told EL PAÍS: “Given the news from the UK, our publishers will consult whether they are proposing changes and what kind of direction they suggest before making any further statements.” Dahl’s books have been translated into 63 languages and sold over 300 million copies worldwide. His provocative and unfettered portrayal of children is one of the most adored aspects of his work, although he has also been accused of racism, misogyny and antisemitism.

Censorship or political correctness?

“It seems that this crosses the line between political correctness and censorship. I’m 42 years old and read Roald Dahl’s books as a child. I reread them as an adult teacher and with my daughter,” said Begoña Regueiro Salgado, a children’s literature and literary education professor at the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM).

Like millions of fans worldwide, Regueiro loves the novels as they were originally written. “He’s not an author for a four-year-old child. The children who read his books must have a capacity for judgment. It doesn’t help when we overprotect children. On the contrary, it casts doubt on their judgment and ability to understand. Of course, I’m concerned about gender issues and know that it’s wrong to call someone ‘fat’ or ‘ugly,’ but the purpose of education is to explain that.”

Regueiro directs a UCM group of literary education and children’s literature researchers that has debated the changes to Dahl’s stories. Almost everyone interviewed for this piece had previously heard about the issue, which shows the enormous impact that it has had. “Adults – teachers, families, booksellers – are the mediators between literature and children,” said Pilar Núñez Delgado, a language and literature didactics professor at the University of Granada (Spain). “We must learn how to teach children that the world hasn’t always been the same. Humanity has a long history and has bettered itself in certain ways.” Some of the people interviewed by EL PAÍS offered alternative solutions, such as including an introduction or footnotes providing context about the period in which the novel was written and about the author.

The global debate quickly extended beyond Roald Dahl to questions about other creative expressions. Should references to the exploitation of child labor during the industrial revolution be omitted? Should a painting of a firing squad be airbrushed into acceptability? How about changing Enid Blyton’s The Famous Five series of children’s adventure stories so that the protagonists drink soda instead of ginger beer? “Imagine if every new edition had to be reviewed to ensure it suited the tastes of that time,” said Núñez.

Xosé Ballesteros, the head of Kalandraka publishing house for children and young people, pointed out that the idea is to head in the opposite direction. “First and foremost, literature must be good. We know that a lot of garbage is published for adults but also for children and young people. Commercial considerations often take priority. Publishers should aspire to disseminate works that last and could become classics.” Ballesteros recalled another recent protest from the opposite end of the political spectrum when in 2015, the conservative former mayor of Venice, Luigi Brugnaro, banned several children’s books for promoting “gender ideology.” Ballesteros also believes that it’s wrong to “distort the style of someone with no say in the matter,” since Roald Dahl died in 1990.

Ethics aside, there are also legal questions. Spain’s Intellectual Property Law grants authors certain inalienable rights, such as preserving the integrity of the work to prevent any deformation, modification, alteration or attack that could be detrimental to a creator’s legitimate interests or reputation. What are the implications in this case? “Dahl wrote the words, and that’s all there is to it. The work and copyright supersede whoever is managing and tinkering with his legacy,” said Carlos Sánchez Almeida, an intellectual property lawyer. His colleague Andy Ramos agrees with this interpretation of the law: “When an author wants to use language and connotations to convey specific ideas, offensive or not, this must be respected.”

Hypothetically, the government could even get involved as the guarantor of freedom of expression and the right of access to culture. “If the original work disappears from the market and only the changed version remains, the government could request a court order to publish the original,” said Ramos. “Readers have the right to view a work of art in its original form,” said Sánchez. According to Ramos, there could even be a class action lawsuit demanding the disclosure of the exact characteristics of the work purchased. As if, somehow, the new versions of Dahl’s stories constituted false advertising, unless they contained disclaimers about the revisions.

Inclusion ambassadors

The revisions to Dahl’s stories were done with the collaboration of Inclusive Minds. This company employs “inclusion ambassadors”, people with diverse life experiences dedicated to detecting where a text may be disrespectful to any sensibility. Some teachers interviewed by The Daily Telegraph pointed out that children’s tastes are changing, and they even find certain views obsolete and passages offensive.

This is not the first time that Dahl’s work has generated controversy. He has been called misogynistic, crude, amoral, antisemitic and racist. His descriptions of the Oompa Loompas, Willy Wonka’s little helpers, as noisy, domesticated pygmies have been heavily criticized, as has Willy Wonka’s creepy seduction of children with succulent but insidious sweets. The author’s family apologized in 2020 for his antisemitic remarks, saying they were “incomprehensible.”

Throughout his life, Dahl occasionally changed his stories to avoid such criticism. Now that Dahl is gone, the Roald Dahl Story Company wants to maintain “the plots, the characters, the irreverence and the biting spirit of the original text.” The challenge ahead is maintaining Dahl’s appeal, which often relies on a bit of offensiveness, and accommodating it to new sensibilities – without his permission.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.