A fake salsa band ignites the rebirth of an old New York record label

The Colombian group Meridian Brothers is releasing an album in tribute to a band that never existed; it is produced by Ansonia Records, a forgotten label that was the seed of the renowned La Fania

A new album will land on the salsa dance floor by the end of this week; one that fuses rhythms from the 1970s with the technological dystopias of the future. Behind it is Ansonia Records, a label that, after its creation in 1949 among Latino immigrants from New York, would produce several merengue, jibara, bomba, guaracha, mambo, and boogaloo albums, before stopping altogether in 1990. This Friday, after more than 30 years, Ansonia Records will return with a salsa album.

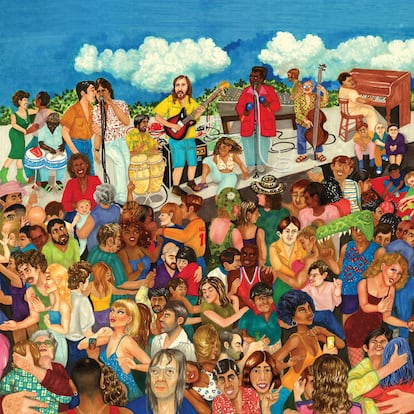

Hermano del futuro, vengo buscando iluminación; brother from the future, I come looking for enlightenment. So says one of the songs from the new album, called Metamorfosis, by the old salsa group Renacimiento. But there is a catch: Renacimiento does not exist. It never did. It is a fake group, and this is a fake cover, explains musician Eblis Álvarez, founder of the Colombian group Meridian Brothers, who had already experimented with various genres, from cumbia to vallenato. A group that practices “tropical cannibalism,” says Álvarez. This year, Meridian Brothers decided to launch a group of salseros straight out of fiction: Renacimiento.

“Renacimiento [rebirth] is the typical name that musicians would give a salsa group in the 1970s,” Álvarez tells EL PAÍS. “For example, in the Nueva Trova movement there was talk of a political rebirth, but at the same time they combined this with a spiritual factor: when one listens to groups like La Columna de Fuego [from Bogota] or Los Jaivas [from Chile], there was a common pattern: everyone was waiting for a rebirth of the soul, and of society.”

Although on stage Renacimiento is made up of five artists — María Valencia, Alejandro Forero, César Quevedo and Mauricio Ramírez, besides Álvarez — when the album was recorded it was the founder who played all the instruments, besides doing the voice of the salsero that accompanies the songs. The album has nine tracks, some similar to the older, slower salsa, and others to the faster, contemporary style. Between the piano, the timbales and the percussion, we find verses with the concerns of the 21st century: love that “communicates by algorithm,” or the threats of atomic bombs that “take us to the cemetery.” Metamorfosis, the single that has already been released, begins with a man who wakes up turned into a robot and longs for a time “when nightclubs really had an atmosphere, not like now, full of cameras, full of drones.”

“I wanted it to sound like salsa from the 1970s,” says Álvarez. “There is no originality, or the originality of this lies in being able to replicate the music as best as possible, but in terms of the material there is nothing original, as it is made with the collective unconscious of Latin America, of Colombia, of Latinos. This is an extrapolation from the 1970s to today, and it speaks of transhumanism, like the matter of highest concern that everything, absolutely everything, is now packed inside the damn cell phone.”

The rebirth includes both the album and the label, as this is the first recording in more than 30 years to be released by Ansonia Records, a company created in 1949 and later forgotten, despite having been one of the first labels founded by a Latin migrant in the United States. Puerto Rican Rafael Pérez, its founder, brought Dominican, Puerto Rican and Cuban musicians from Latin Harlem or the South Bronx, who had not found a home among American record companies, to several studios. He produced his records before the time of the powerful Fania, which made New York salsa famous.

To Liza Richardson, an American radio host who was also a music supervisor on series like Narcos or the movie Y tu mamá también, Ansonia Records is a gem. In the early 1990s, she found an Ansonia album in the station’s archives and, fascinated by the label’s production, became close to the heirs of Pérez. In 2020, she bought the record label with the intention of reactivating it. She, with the help of a small team, has begun to digitize more than 5,000 Ansonia-produced songs; an eighth of them can already be found on streaming platforms like Spotify.

Souraya Al-Alaoui, manager of Ansonia Records, explains that most of the artists chosen by the label were focused on the Latin American diaspora. That was their base; they valued the traditional sounds from islands like Cuba or Puerto Rico, and were not looking to become westernized.

“Johnny Pacheco, founder of La Fania, started with Ansonia Records, and Ansonia was an inspiration for what would later become La Fania,” says Al-Alaoui. “Ansonia was also a pioneer as a label owned by a Latino, an independent label with a founding message: ‘this is from us and for us.’ That’s why it was an inspiration for what came after.”

Over the years, La Fania grew and the seed of Ansonia Records faded away. The label never managed to promote its musicians in concerts like La Fania did, and after the arrival of the digital world, they did not set up a website or try to upload their music to any streaming platforms. Thus, it became a label that was only known by a small group of music lovers, like Liza Richardson and Eblis Álvarez.

“Now, we are hoping to release a new record every year, and we are thrilled to start with this one by Meridian Brothers,” says Richardson. “This is an album that looks to the past but tries to move towards the future, and that is exactly what we are trying to do: look to the past to, at some point, be able to grow again, to thrive.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.