The Thyssen’s disputed Pissarro: a masterpiece that symbolizes the ongoing struggle to return Nazi-looted art

The US Supreme Court’s ruling in favor of the Cassirer family has reopened one of the most famous and longest cases of plundered art in history

On December 15, 1897, Camille Pissarro wrote a letter to his son Lucien in which he announced he had rented a room at the Grand Hôtel du Louvre, from where he could work. “I’m delighted to have the opportunity to paint these Paris streets that we tend to consider ugly, but which by contrast are so silvery, luminous and full of life. They are the height of modernity!” The doyen of the impressionists was 67 and suffering from an illness affecting the tear duct of his left eye, which had forced him away from fields where for decades he had lent a new dimension to painting in the open air. Avoiding the dust and wind of Paris’ thoroughfares, he settled for looking out of his window and completed 15 paintings of a city that was in the throes of the Dreyfus Affair and Émile Zola’s famous J’Accuse…! letter published in L’Aurore that laid bare the antisemitism of the Third French Republic. Pissarro’s art dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, sold one of the most admired of the series, titled Rue Saint-Honoré, dans l’après-midi. Effet de pluie (“Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain”) in 1900 to the Cassirers, a family of Jewish industrialists and art collectors. Now, 125 years after Pissarro sat at his window to paint, the work is at the center of an international dispute that has lasted for more than two decades.

The sole living descendant of the first owners of the painting, David Cassirer, is a retired 67-year-old musician living in San Diego. As he tells EL PAÍS in a lengthy telephone conversation, he is determined to take a battle “started 23 years ago” by his father, Claude Cassirer, “to its conclusion.” Cassirer wants the Thyssen-Bornemisza Foundation to remove the painting from display at its museum in Madrid and return to the family a work of art that was looted from his great-grandmother, Lilly Cassirer, by the Nazis in 1939.

After two court rulings against the Cassirer family, one in Los Angeles in 2018 and another on appeal at the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, the case reached the US Supreme Court in January. On April 21, it found in favor of the Cassirers. The decision, which more than anything was concerned with unifying procedural processes, did not rule on the fate of the painting. The Supreme Court was, however, categorical in its decision to knock the ball back into the Court of Appeals as it ruled the judge had erred in applying the conflict of laws, which decides which of Spanish and Californian law prevails in a dispute that involves a US citizen as plaintiff and a foreign state as defendant: the Spanish state acquired the Pissarro in 1993 along with a further 775 works from the collection of Baron Hans Heinrich von Thyssen-Bornemisza for $350 million. If the federal conflict rule is applied, as it was previously, then Spanish law prevails, and Spain’s view is that the Pissarro is perfectly fine where it is. But if state conflict law is applied, what happens then? As with much of the entire story, it depends who you ask.

According to Cassirer’s lawyers, the “logical” answer is that California substantive law will prevail, which states that a person who receives stolen assets cannot consolidate a title of ownership no matter how much time has passed. The Thyssen Foundation’s lawyers, meanwhile, are “99%” certain that the merits of the case will be decided by Spanish law, under which the right of usucaption states that the public possession of the painting for a period of six years is sufficient to consider the museum its legitimate owner (12 had passed between the museum opening its doors and the 2005 complaint lodged by the Cassirer family in Los Angeles).

Taddheus J. Stauber, an attorney with the Nixon Peabody global law firm that has represented the Foundation since then, pointed out that the judge who first handled the case in 2018, John Walter, went through the exercise of imagining what would happen is the state conflict rule was applied and obtained the same result that led him to rule against the Cassirers. “There is little or no relation between California and the painting in question. It was acquired with Spanish public funds and has been in Europe for decades, since the baron bought it in 1976. Its only link with California is that the plaintiffs [David Cassirers’ parents, who have both since died] moved to San Diego when they retired. We have no doubt that Spanish law will prevail,” Stauber says.

In the view of Bernardo Cremades, whose family law firm took up the case as amicus curiae in 2017 to assist the Cassirers on behalf of the Federation of Jewish Communities of Spain and the Jewish Community of Madrid, that argument is weak, because Walter’s theoretical test was carried out “in a very superficial manner.”

“It was done in passing, and without getting to the crux of the issue. Anticipating what a judge is going to decide seems to me to be pure speculation,” says Cremades. “I am surprised that Spain continues to lean on technicalities not to comply, unlike other countries, with international agreements regarding the return of are stolen by the Nazis. I am referring to the Washington Principles [on Nazi-Confiscated Art] and the Terezin Declaration [on Holocaust Era Assets].”

Judge Walter also made reference to both treaties – signed by Spain in 1998 and 2009 respectively – in is ruling. The last paragraph of the April, 2019, ruling reads: “The refusal of the museum to return the painting is incompatible [with the agreements]. However, the court has no alternative but to apply Spanish law and cannot force the Kingdom of Spain or the Thyssen-Bornemisza Foundation to comply with its moral commitments.”

David Cassirer celebrated the Supreme Court ruling as a great victory: “We thought we could win, but I never dreamed of getting a unanimous verdict,” he said of the decision that brought the nine magistrates of one of the most divided Supreme Courts in decades into rare agreement. “It is very encouraging, and it sends a message to Spain and to museums around the world: it is not right to profit from the Holocaust. This painting was stolen from Holocaust victims by the Nazis. Spain should return it instead of carrying on with this costly litigation.”

On the score, all parties are in agreement. According to data provided by the Thyssen, Spain has paid €2,735,845 in lawyers’ fees and €310,947 in other costs. Cassirer says that his expenditure is “between $10 and $20 million,” leading him to suspect the numbers released by the Foundation are “a lie.” If he managed to recover the Pissarro, Cassirer says he will have no choice but to sell it. “I have thought about doing it on the condition it is publicly displayed,” he adds. The three firms that have worked on Cassirer’s case, led by one of the most famous attorneys in the US, David Boies, whose previous clients include Al Gore, Harvey Weinstein and Virginia Giuffre, have all staked their fees on a favorable ruling. “We have a lot of mouths to feed,” says Cassirer.

Whatever the outcome of one of the most famous cases of its kind in history, the fact that it went to the Supreme Court has served to put the spotlight back on the history of a canvas and a family that were closely mirrored by the fate of many of Europe’s Jews during the darkest

period of the 20th century. To reconstruct the sequence of events it has been necessary to view judicial documents and archives in Washington and to carry out dozens of conversations, many of them confrontational, with Cassirer, representatives of the Thyssen Foundation, lawyers for both parties, experts on Pissarro and specialists in the recovery of stolen art.

The painting came to the family via the famous gallery that Bruno Cassirer, a leading expert on the impressionists, and his cousin Paul operated on 35 Viktoriastrasse in Berlin. The Cassirer family was one of the most famous Jewish lineages in Europe, with members including the philosopher Ernst Cassirer and the orchestra director Fritz Cassirer. The latter inherited the Pissarro from his father, Julius, in 1924 and he in turn left it to his wife, Lilly, when he died two years later. The couple had an only child, Eva, who died when she was young, during the influenza pandemic of a century ago, shortly after giving birth to her only descendant, Claude, who launched the action against the Thyssen Foundation before passing away in 2010.

Lilly remarried at the age of 63, to a famous doctor called Otto Neubauer, who was stripped of his practice in Munich when the Nazis came to power in 1933 due to his Jewish lineage. In 1939, fearing “arrest by the Gestapo, without and apparent reason, and deportation to Dachau,” the couple fled Germany for England, where Neubauer was employed by the University of Oxford to continue his study of cancer.

Shortly before they left, an art dealer sent by the Third Reich arrived at their home to assess what cultural property the Nazis were planning to remove from the country. They were handed 900 marks for the Pissarro, an “insulting” price as an Allied document noted at the end of the war. Lilly didn’t even receive the money: it was paid into an account that was already blocked. The dealer then exchanged the Pissarro, who as a Jewish painter carried little interest in Germany at the time, for three pieces by 19th century German artists. They were owned by another Jew, Julius Sulzbacher, who unsuccessfully attempted to take the Pissarro with him on his flight to Brazil. Requisitioned by the Gestapo, it was sold at a 1941 auction in Dusseldorf to a man named Ari Walter Kampf. The work was sold again two years later in Berlin for 95,000 marks. All trace of it was lost for a decade, until it reappeared in Los Angeles in 1951.

Lilly Cassirer was unaware of the canvas’ journey: she assumed it had been lost or destroyed during the war. She died in 1962 in Cleveland, where she had moved after being widowed for a second time to live with the family of her grandson, the photographer Claude Cassirer. Four years earlier, after a decade of litigation, Lilly received compensation of 120,000 marks from the Federal Republic of Germany, of which she had to pay 14,000 marks to the painting’s previous owner, Sulzbacher. The agreement also stated that Lilly would not relinquish the right to ask for the restitution or return of the painting, if the case arose.

Both parties are more or less in agreement that the compensation, fixed by the market value of Pissarro at the time, was fair, but they differ on how the implications of the deal should be interpreted. In Cassirer’s view, the museum’s stance that it compensated his great-grandmother is merely to “clear their conscience.” “They want to make us out to be greedy, to imply that we are looking to be compensated twice. It’s a classic: stirring up stereotypes about Jews. But there is a big difference between reparation and restitution, and anyway, the money we received would have to be reimbursed to Germany if they return the painting,” he says. Evelio Acevedo, managing director of the Thyssen, counters: “It is often forgotten that they were compensated, and when it mentioned the impression is that the amount they received was miserly, which is not the case. They could have bought another Pissarro.”

Cassirer shows a photograph of the canvas hanging in Lilly’s elegant Berlin apartment in the 1930s to underline that the family does not want “another Pissarro,” but the same one that was in the family for 40 years. Cassirer still possesses many of the other items in the photograph. When his parents moved to San Diego to be close to their children (David had a sister, Ava, who died in 2018), he commissioned a copy of the Pissarro to hang in the sitting room of the new house. Before moving to California, Cassirer’s parents had lived in Cleveland, where they arrived “without a cent” in 1941. The German occupation of France caught them by surprise but they were able to flee to Morocco, where they nearly died of dysentery in a refugee camp. A Jewish association directed them to Cleveland, where there was sizeable Hebrew community. There, Claude became a “very popular photographer, with important clients,” according to his son. Whenever they announced an upcoming trip to Europe, “I would always show them a picture of the Pissarro, to see if they came across it,” he says.

The eureka moment arrived in December, 1999, when a friend of the family sent a photograph of an image of the Pissarro in a catalog of Baron Thyssen’s collection in Lugano, Switzerland. “Overcome with shock and anger, my father decided he would not stop until Lilly’s painting no longer honored the legacy of a family of steel industrialists who supported Hitler at the beginning,” Cassirer says, in reference to Fritz Thyssen, who contributed to the Führer’s rise but ended up being persecuted by the Third Reich. “Without him, this monstrous being would never have been more than an average painter. Wouldn’t that have been a better world,” he adds.

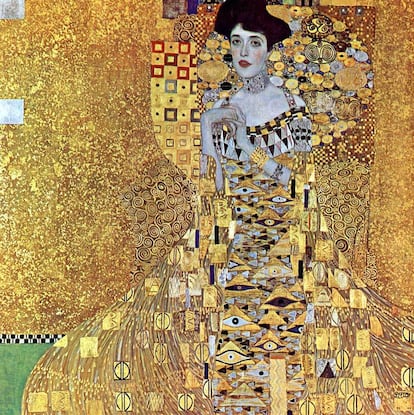

It took the Cassirers a few months to discover where the painting was, with the help of Ronald Lauder, president of the World Jewish Congress: it was by then property of the Spanish state and hanging in the Villahermosa palace in Madrid. After asking fruitlessly for its return, the Cassirers filed a lawsuit in Los Angeles in 2005, buoyed by the success of Randol Schoenberg (grandson of the Austrian composer) before the Supreme Court, which granted him the right to litigate in California what was surely the most famous case of the recovery of Nazi-looted art ever undertaken: Maria Altmann’s claim against the Austrian state for the recovery of five Klimts stolen from her family. Their eventual restoration was the stuff of Hollywood, to the extent that it ended up as a movie, The Woman in Gold, starring Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds. The most famous painting in the collection, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, also known as The Woman in Gold, sold for a then-world record $135 million in 2006.

After locating the Pissarro, the Cassirers started to piece together its history. From the time Lilly lost track of its whereabouts to when it was bought by the baron in Los Angeles for $300,000 in 1976, it had been around the block a few times. The painting arrived in Los Angeles in the possession of a German merchant called Frank Perls, who was Jewish – “ironically,” notes Cassirer, who describes him as a “super-thief.” During the war, Perls had worked as a translator for the US Army. He sold the work to a noted art lover called Sidney Brody, who was also Jewish and returned it a few months later because, according to Cassirer, he found out that it was a looted piece. A year later, Perls sold the painting again to the heir to a department store fortune in Saint Louis, where it remained for 20 years. It was offered to Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza through a well-known New York dealer, Stephen Hahn.

Cassirer describes all of these transactions as conspiracies carried out stealthily, “by a bunch of crooks on the stolen art black market.” Stauber, the Foundation’s attorney, says that the reputation of these dealers “is beyond doubt,” pointing out that none of them appear “on any of the lists published at the end of the war of art dealers who collaborated with the Nazis,” adding: “I find it appalling that he would throw such accusations against members of his own community lightly.”

Cassirer also considers it relevant that the painting still bears part of the stamp of the gallery belonging to his predecessors, Bruno and Paul Cassirer, which was discovered when an expert was dispatched to Madrid to look at the canvas. When it was removed from the wall at the Thyssen Museum and the frame removed (evidence, notes Acevedo, of the “transparency” the museum has exercised “at all times”), fragments of the stamp could be seen: “Berlin,” “Vikto” – part of the street name – and “Kunst und Verla,” for Kunst und Verlagsanstalt, the name of a gallery and publisher. Cassirer believes that “someone erased the names of Bruno and Paul at some point” and that “Hahn knew exactly what that stamp meant as did, as an art lover, the baron.” Cassirer suggests that they didn’t’ want to see the stamp “through the blindness of self-interest. It is outrageous that the Spanish specialists state they did not realize what was in front of their eyes when they bought the painting as part of the lot. It was one of the most famous galleries in Europe!”

Stauber says the Foundation does not know if the stamp was intact when the baron bought the painting, or in what condition it was when it arrived in the hands of the Spanish state. “But it doesn’t matter, because a stamp of this kind only indicates that the painting passed through that gallery, nothing more. It does not prove in any case that it was the property of Lilly Cassirer, and Judge Walter made that very clear in his ruling. Curiously, this issue of the stamp has only entered the conversation in the last few years, at the same time as they have run out of arguments. When the lawyer changes, the story changes.”

In the initial ruling it was also established that the Thyssen Foundation bought the Pissarro “in good faith,” although historian Miguel Martorell, author of a book on the Nazi looting of art, advises caution. “Bad faith is very difficult to prove in usucaption; it is not the kind of intent you put down in writing. What does seem clear to me is that the baron did not do enough to verify the provenance of the painting,” he says, adding that the museum lacks perspective on the matter. “They sometimes give the impression that they have forgotten, among so much legalese, the story that lies beneath, which is that of a victim of the Holocaust seeking reparation for terrible damages.”

Stauber points out that the Pissarro does not feature on any list of stolen art compiled in the 1970s, because the family had not registered it, and that awareness of the issue at that time was not what it was in the 1990s. Acevedo, meanwhile, notes that the Washington Principles “do not establish an obligation in every case to return pieces that were looted. They aim to protect the rights of all parties in an operation. Those that bought in good faith, as the Foundation undoubtedly did, also have rights, which are protected by these Principles. Those affected by looting were duly compensated, and as such the spirit of these Principles has already materialized in this case.”

Stauber, who participated in the drawing up of the Washington Principles when he was a young attorney, adds that the multilateral agreement “is also designed to encourage respect for the laws of other countries. We cannot impose US law around the world. Imagine a Spanish court accepting a claim against The Smithsonian, for example. It’s unthinkable.”

Another matter on which the two parties differ is what the baron did with the painting before selling it to the Spanish state. Cassirer is in no doubt: everything possible to keep it hidden. To back his theory, he produces a photograph published in Architectural Digest in 1988 in which the Pissarro can be seen hanging in a small room at Villa Favorita, Heinrich Thyssen’s Lugano

mansion. The Foundation, on the other hand, says this proves quite the contrary. “If he was seeking that [to keep the painting hidden] why would he let one of the biggest decoration magazines in the world publish something he didn’t want seen?” asks Stauber.

The Foundation also commissioned a report from historian Laurie Stein, an expert in stolen art. In it, Stein says that between 1979 and its eventual arrival in Madrid, the painting was displayed at exhibitions in nine different countries, from New Zealand to Germany. Cassirer, however, says this is not the case. “They have used archive photographs to fake that the painting was in London or Tokyo. They have not been able to produce anything, not a single image or newspaper article. How is it possible that one of the most famous works by one of the most famous of the impressionists passed through these capitals without trace?”

Stauber responds to this accusation by pointing out that the baron’s collection “was one the best-known in the world” and that when it was put up for sale “it was courted by the Getty Foundation in Los Angeles, by the UK and Germany. The announcement that it would end up in Madrid was global news, impossible to keep secret,” he says. One of the reasons the baron decided to sell to Spain was that the government promised to maintain the collection intact, an agreement sealed by law. When asked if this law will have to revised if a California court rules the Pissarro must be returned, Acevedo replies: “This scenario is not even on the table, because there are no reasons to believe that the current ruling is going to change.” Cassirer, once again, is not in agreement with that statement.