Queen Mary: the ignoble end of a seafaring giant that fought the Nazis and ferried royalty

The Queen Mary was the fastest ship in the world between 1938 and 1952 and one of the finest ocean liners of the golden age of trans-Atlantic travel, also serving during the Second World War, but now languishes in Long Beach in need of restoration

Eighty-eight years ago, when it was launched from the Clyde River in Scotland, the RMS Queen Mary was destined to rule the oceans. Ocean liners had enjoyed a golden age between the late 19th century and the outbreak of the First World War, among other reasons due to emigration to the United States, but it wasn’t until the inter-war period that the competition between shipping lines to flex their maritime muscles reached its zenith. That is why the construction of the Queen Mary, completed in 1934 and named in honor of the wife of George V and the grandmother of Queen Elizabeth II, Mary of Teck, attracted so much attention.

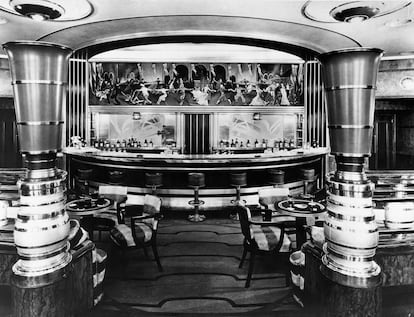

The vessel had the biggest hull ever seen, over 300 meters in length, 12 decks and capacity for 2,139 passengers and 1,101 crew. BBC radio announcer George Blake, present at the launch, described the ship as a “great white cliff, huge and overwhelming.” Cunard-White Star, the shipping line that commissioned the Queen Mary, abandoned its standard classicism and devoted its interior design to art deco. But the Queen Mary’s primary goal was national pride: at a time when nations were vying for prestige on the open sea, the Queen Mary was the fastest vessel ever launched and superior to its closest rival, the French ship SS Normandie.

The Queen Mary had swimming pools, tennis courts, libraries and kindergartens, among other services. The vessel’s abundance was matched at the time by only a handful of other ships and among its passengers were world leaders and politicians, royalty and Hollywood stars such as Audrey Hepburn, Greta Garbo, Clark Gable, Elizabeth Taylor, Judy Garland, Buster Keaton and Fred Astaire. Among other passengers, in second and third class, were middle-class American families who could afford a couple of weeks’ vacation in Europe, Europeans who wanted to breathe the fresh air of the New World and those emigrating to the United States in search of a new life.

The connection between the British and US coasts heralded the most prestigious chapter in the tussle for the maritime crown. As such, from its inaugural voyage in May 1936, the goal of the British liner was the Blue Riband, an unofficial award bestowed on the ship that records the fastest trans-Atlantic crossing and which at the time was held by the SS Normandie. The Queen Mary, which like the Titanic ran between Southampton and New York, didn’t take long to relieve France of the honor. In August of the same year, on an east-west crossing, the ship’s 16 turbines, which emitted an output of 160,000 horsepower, reached an average speed of 30 knots (35mph). The voyage was completed in four days and 27 minutes. A year later the Normandie would beat that time again, but in 1938 the Queen Mary regained the Blue Riband with a voyage that knocked two hours and 12 minutes off the four-day voyage and held it until 1952, when the United States beat her time.

With the outbreak of World War II, the Queen Mary abandoned her luxurious and gentlemanly pursuit of seafaring records to take on a task of much greater importance. Repainted in navy gray – leading her to be nicknamed the “Grey Ghost” – the Queen Mary became a transport ship carrying troops from Australia and New Zealand to Britain. On one voyage alone, 15,000 soldiers were ferried across the world and throughout the war, due to its speed, it was able to easily escape the attentions of German U-boats. The Nazi regime was so incensed it put a price on the Queen Mary’s head. It also served to transport Winston Churchill, hidden among the passenger list with various pseudonyms including Colonel Warden.

Paradoxically, it was due to orders not to halt or alter course to prevent attacks from beneath the waves that led to one of the greatest wartime tragedies in the British rearguard. In 1942, off the coast of Derry in Northern Ireland, there was a communication breakdown between the officers on the decks of the light cruiser HMS Curacoa and the Queen Mary, which collided with the much smaller vessel and carved it in half with the loss of 239 of the cruiser’s 338 crew.

In the late 1940s, some of the luster of the golden age of the ocean liners began to fade. The development of jet aviation during the war had opened the skies and by 1952, cities as far apart as London and Johannesburg had been connected by air (although the first flight between the two required 24 hours and five stopovers). Achievements such as these heralded the beginning of the end for the great vessels. The glamor that had created such allure around sea voyages had now been transferred to aircraft.

In 1965, the entire Cunard-White Star fleet was operating at a loss and the company decided to halt operations. The Queen Mary made her final voyage in 1967 and was subsequently sold off to the highest bidder: the city of Long Beach, California. Many of the vessel’s engines and motors were stripped and it was turned into a tourist attraction with its owners proposing a multi-concessionaire system – including a museum dedicated to marine biologist Jacques Cousteau, a hotel and a restaurant all coexisting in the interior, with guided tours operated by the city’s tourism authorities – that failed to work as planned.

That was when Disney became involved. Jack Wrather, a millionaire who held fond memories of his own trans-Atlantic voyages, signed a long-term concession to manage the ship but in 1988, just after his death, Disney bought his estate - due to a vested interest in the Disneyland Hotel in California, which Wrather had owned – which included the Queen Mary. The vessel’s financial viability remained elusive however, particularly after the entertainment behemoth shelved plans for an adjacent theme park of which the Queen Mary would have formed part. Disney finally renounced management of the ship in 1992, and the Queen Mary closed her doors to visitors.

Since then, ownership of the Queen Mary has changed hands several times, with the same result every time: a lack of financial viability and deterioration of the ship’s structure. It has been closed since the Covid-19 pandemic began and last year the city itself took the reins after the previous owners went bankrupt. The Los Angeles Times reported in February that Long Beach authorities will allocate $5 million over 2022 to prevent the vessel from flooding. This is merely a stop-gap to put off an even greater problem: there have been studies, cited by the newspaper, that suggest it will take $289 million to carry out a complete upgrade of the Queen Mary. The city’s government has even floated the idea of sinking her, but a previous backlash from residents who are keen to ensure the ship remains where she is when the possibility of moving it to a new location was raised suggests this is not an option in the short-term. It would be enough, in the same way that the Queen Mary evaded enemies at sea during the war, for this jewel of the golden age of maritime voyages just to be profitable enough to cover the costs of repairing the significant damage the ship has suffered through years of neglect.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.