Hurricane Katrina survivors describe how it changed their lives 20 years on

Four residents recall the passage of the 2005 storm, which left 1,400 people dead and caused extensive property damage, and the recovery of New Orleans afterward

The floods brought by Hurricane Katrina ebbed a long time ago, but the scars are still raw in some parts of New Orleans. Just set foot inside Mercedes’ Place, a bar south of the Lower Ninth district, one of the hardest-hit by the storm when it made landfall on August 29, 2005, dumping 25 centimeters of rain and bringing wind gusts of up to 200 kilometers (125 mph) per hour. But that wasn’t the worst of it. The flooding went on to break the levee system, leaving 80% of the city underwater.

“The water marks were up to here,” says Deborah Gibson, inside Mercedes’ Place, while pointing to a window more than two meters high. The 65-year-old drinks a beer inside the establishment that her mother, Mercedes, opened in 1989 in this African American neighborhood which lies below sea level in an area that is easily flooded. For this reason, most of the houses stood on columns. Even so, Katrina forced a change in the script. “We all have a history with the hurricane here,” she says. The Gibsons’ is one of pride. “We are the only business that reopened and recovered after the storm.”

At the back of the premises sits the matriarch, Mercedes, at her kitchen table. The 86-year-old lived for two years in exile in Franklin, a town an hour and a half west of New Orleans. When she returned, her premises had been looted. “They took everything, down to the last coin,” she recalls. “Those were terrible times.” Several of the inhabitants received $10,000 to help them put their lives back together. Some did, but the Lower Ninth was no longer the same. “This changed forever, it’s a completely different place. Most of the people who left did not return. Now it’s mainly white,” Mercedes says.

Some residents of the Lower Ninth still remember the sound the levees made when they burst. The system was created in 1965 by the federal government to protect the low-lying areas of the metropolitan region. The Army Corps of Engineers set out to build infrastructure that could withstand disasters like the one in 1915, when a powerful hurricane wiped entire neighborhoods off the map, leaving 275 people dead and the equivalent of $300 million in damages. Katrina devastated this infrastructure, forcing the Army Corps of Engineers to admit it had used cheap materials that it had failed to maintain.

Climate anxiety

When the levees gave way, they caused the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain to rise an average of 5.4 meters. In 2017, the National Hurricane Center adjusted the number of deaths caused by Katrina in six states, lowering it to 1,392 — compared to 1,833 — after studying the death certificates. As contemporary natural disasters go, it had the highest death toll after Maria, which left 2,981 victims in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands in 2017.

Katrina caused $108 billion in property damage, making it the most expensive hurricane in history. Bobbie Green lives east of New Orleans and defines herself as a “Katrina baby.” She was just nine when she was forced to evacuate the city with her family. She lived for a year in Houston, Texas. When they returned, her parents found their home severely damaged, populated only by stray cats in search of food. “I definitely suffer from extreme anxiety every hurricane season... I am always poised for either fight or flight,” she says.

The storm shaped Green’s future. She is now an environmental activist and educator who flags up climate injustices with the organization Black Girl Environmentalist. “Black and Latino people are still the most affected because we live in those low-lying areas and we are very attached to our homes. We fight against the gentrification that might force us out to other places,” she explains. What bothers Green the most is how the population of New Orleans has been labeled resilient: “We are fed up with it. We are tired of being resilient. No one wants to face another Katrina,” she says.

Louisiana’s wetlands are disappearing at an alarming rate. It is estimated that each year the southern state loses territory equivalent to an American football field. Half a million hectares of this natural barrier against hurricanes has disappeared in just under a century. Since Katrina, work has been done to restore it. Some organizations have planted vegetation in the swamps. Banks have also been built with recycled materials, such as oyster shells or broken glass. But climate change is moving at a much faster rate than recovery. Many coastal communities continue to face existential threats each hurricane season, which lasts from June to November.

The heroes

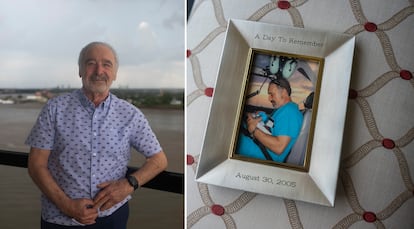

In 2021, Hurricane Ida hit the Gershanik family after they had managed to survive Katrina intact. The storm also made landfall in Louisiana on August 29, a macabre coincidence that seemed to highlight the fact that catastrophes can strike twice. “On the outside, our house was perfect for 40 years, but you just had to enter to realize that the damage was irreversible,” says this 83-year-old Argentinian doctor from Concepción del Uruguay.

Gershanik now lives with his wife Ana Esther in an apartment in downtown New Orleans. From there you can see vast ships sailing down the Mississippi and the storms that form on the horizon. In the couple’s dining room, there is a photo of the doctor inside a helicopter. In his arms is a tiny baby. The image is in a frame that reads: “A day to remember: August 30, 2005.”

Gershanik doesn’t like the word hero, but everyone in town considers him one. As head of neonatal at Memorial Hospital, he headed up an operation to relocate 16 babies in incubators from the sixth floor to the roof of the building hours after Katrina arrived. The hurricane complicated the task by flooding the ground floor, and the babies had to be moved through windows and passageways. “Fortunately, we had an army of volunteers, people who had been trapped in the hospital because they were relatives or husbands of the nurses. It was a whole world of people who helped us pick up the incubators, which weighed more than 100 kilos,” he recalls. When they reached the roof, the wait for the rescue helicopters began.

The babies’ monitors were powered by light generators located on the second floor. Gershanik began to watch with concern as the water level rose, threatening the only source of energy. “They were children who were in a critical condition,” he says. Their focus was on a 26-week, 680-gram premature baby with a chronic lung condition. The helicopters did not take any patients away for four hours. “I have to do something. This boy is dying on us,” the doctor told the person in charge.

When the next helicopter arrived at the helipad, Gershanik pushed the incubator towards it. He received a disapproving look from the pilot. The weight of the machine was too much. The doctor convinced him to take a couple of oxygen tanks and boarded with the child in his arms. It is the moment that was immortalized in the image. They had been flying for 10 minutes when the pilot told him that they had to land again to refuel. “I didn’t have a monitor, but I pricked the child’s foot and he responded,” says Gershanik, who took advantage of the stopover to change the child’s oxygen tank. “I was given a helping hand from above with that stopover because if I hadn’t changed it the child would have died,” he says. Forty minutes later, they arrived in Baton Rouge.

Every year, that child, now the adult Christian Stewart, celebrates his birthday by traveling to New Orleans to have hamburgers with the doctor who saved his life. It is a tradition both maintain to this day. The actions of this doctor and others from Memorial Hospital were brought to the small screen in 2002.

Gershanik has preferred to pay tribute to the unsung heroes and donated a monument dedicated to the thousands of anonymous immigrants, mostly Hondurans, who rebuilt the city. The sculpture was unveiled in 2018 in Crescent Park and shows a man climbing a roof, another carrying wood and a woman sweeping. A bronze figure looks at the waters of the Mississippi that threaten the city.

The resurrection of New Orleans

An estimated 91,500 homeowners asked the government for help to rebuild their homes. The government paid out $9 billion to the victims of Katrina and also Rita, which hit the coast of Louisiana just weeks later. But rebuilding the city took much more than federal money and immigrant labor. The social fabric had to be restored. Carlos Miguel Prieto, a conductor, signed a contract to become music director of the Louisiana Symphony just a week before Katrina made landfall. While in Seoul, he saw the havoc the storm wrought on the city he would soon call home. The organization asked if he wanted to back out. “I didn’t hesitate to double down on my commitment,” he says. It was the beginning of 17 years at the helm of the state orchestra.

When he finally landed in New Orleans, in October 2005, Prieto was faced with a terrifying scenario. Four harps and other instruments were ruined in the flood, water covered the concert hall and destroyed the Orpheum Theater. “We couldn’t do anything. We canceled the season and became a traveling orchestra,” he recalls. The Nashville Symphony opened its doors in October to the musicians for a benefit concert. The event was attended by people who had lost everything. The musicians and the audience exchanged stories. Other orchestras in the country repeated the invitation, knowing that the music would help heal wounds.

At the end of that month, at the Lincoln Center in New York, Prieto shared the stage with Lorin Maazel, James Conlin, and Leonard Slatkin to conduct an orchestra made up of members of the New Orleans ensembles and the New York Philharmonic. Israeli violinist Itzhak Perlman, jazz musician Wynton Marsalis and singer-songwriter Randy Newman participated. Newman performed Louisiana 1927, a song about a flood that has become the unofficial anthem of New Orleans. “They shouted ‘thank you, thank you!’ It was very emotional,” recalls Prieto.

“Like everything after Katrina, the survival of the city’s cultural institutions was in question. And every time one of these made a comeback, as the Louisiana Symphony did, the audience took it as a total triumph,” says Daniel Hammer, the president of the Historic New Orleans Collection museum.

The city’s musicians were homeless. “We were itinerant for 10 seasons. Something that could have been a nightmare became an incredible opportunity to reinvent ourselves and connect with the public,” says Prieto. People followed them wherever they went. “We became a beacon of hope,” he says.

It took a decade for the Orpheum Theater to reopen its doors, which it did in September 2015. Prieto says Beethoven’s Ninth sounded different when it was first performed in the new auditorium. “It resonated differently after a catastrophe like that. What we did was not entertainment. It was a necessity,” he says.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.