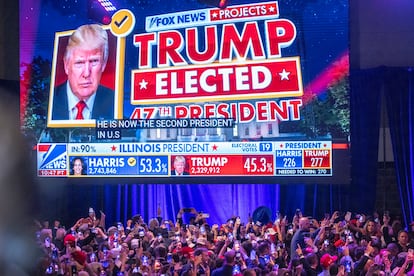

Six takeaways from Trump’s victory: Polls, false surprises and crypto millionaires

EL PAÍS data expert Kiko Llaneras share his insights into the 2024 election, political forecasting and why the Republican is consistently underestimated

Here are six interesting takeaways from the U.S. election between Republican candidate Donald Trump and his Democratic opponent Kamala Harris.

1. Beware of blaming abstention

It is being reported and repeated that Trump won the popular vote by four points — the total number of votes nationwide — but that figure is premature. Millions of votes are still to be counted, with about six million remaining in California alone. According to projections by The New York Times, Trump is likely to win the popular vote, but by a margin of one or two points over Kamala Harris.

This also casts doubt on explanations of the result that focus on voter turnout. It is being suggested that Harris lost millions of votes, and that is why she was defeated. However, this analysis is premature, as the final vote count is not yet available. The overall turnout could end up being equal to or even higher than the 2020 election. For now, patience is needed before drawing definitive conclusions.

2. Trump’s victory was not that overwhelming

In 2020, Joe Biden won by a 4.5-point margin over Trump, meaning that, overall, the country has shifted by about six points in favor of the Republican. This shift is roughly equivalent to 3% of the electorate switching parties.

However, society has not undergone a dramatic upheaval. Four years ago, the Democrats won with 51% of the vote to the Republicans’ 47%. Now, the Republicans are on track to win with 50% to 48%. So, why is there talk of a “red wave”? It’s because the map of states has turned red, with several key territories flipping. But in terms of votes, this shift isn’t as large as it may seem. The number of Americans voting for Democrats or Republicans is actually quite similar to the breakdown in 2020 — and even to that of 2016. Power may be changing hands and this is consequential, but we are perhaps exaggerating the extent of voter swings.

3. The result was not a surprise

It’s surprising that so many people are surprised! Polls — and prediction markets, for that matter — have been indicating for months that the race was close, with Trump often slightly ahead in terms of his chances of winning the presidency.

As we clearly stated in our last analysis, published prominently in all our headlines: “Harris and Trump are tied in terms of their chances of winning; however, this doesn’t mean the result will be close.” Counterintuitively, the most likely outcomes were a red or blue wave, given the way the American electoral system works. I’ve often used the analogy of flipping a coin: you can’t predict whether it will land heads or tails, but that doesn’t mean it will land perfectly even! A tie is rare. As we noted on Tuesday, when the elections were simulated, the most probable outcomes were a Trump wave (23%) or a Harris wave (16%). That’s why I projected 306 electoral votes for Trump in the newspaper’s poll.

EL PAÍS was not the only publication to issue this warning. Similar analyses were presented in The New York Times, ABC News, Forbes, and The Washington Post. Many people may have been surprised by the outcome, because not everyone follows the news minute by minute. But the forecasts and insights were clearly laid out for those who did.

4. What happened to Fredi9999?

You may recall that during the campaign, I followed the predictions on Polymarket, the prediction platform based on blockchain technology and cryptocurrencies, where thousands of people placed bets of varying amounts. I also mentioned Fredi9999, an anonymous user who wagered millions in favor of Trump, and whose activities we could trace because it was recorded on the blockchain. Initially, there was speculation about their identity, with concerns that they might be part of a conspiracy to favor the Republican’s win. However, it seems confirmed that the user was, in fact, a French trader. Fredi9999 moved the market with their multimillion-dollar bets, both on Polymarket and beyond.

Interestingly, the betting community ultimately validated the trader’s position because they did not inject enough liquidity into the platform to counterbalance their bets. As a result, Fredi9999′s radical wager on Trump’s victory has paid off spectacularly: according to The Wall Street Journal, the trader has made $50 million in profits.

5. Prediction markets shouldn’t exaggerate their success

Over the past few months, I’ve shared predictions from three different sources: survey-based models (such as those from The Economist and Nate Silver), markets driven by enthusiastic forecasters without money (like Metaculus), and markets with financial stakes (such as Polymarket or PredictIt). I value all three methods, which is why I’ve included them in our probabilistic prediction average.

It’s absurd to try to choose between them — because they can all be combined — but some proponents of each method seem more interested in competing to elevate their approach above the others.

In this battle, Polymarket has emerged victorious. They gave Trump a 60% chance of winning, while models based on polls and Metaculus gave him a 50% probability. First of all, I’m glad that there’s a prediction market with enough size and liquidity, as it can be useful for predicting everything from sports outcomes to political events, which go beyond what can be estimated with polls. However, the celebrations from Polymarket and its followers seem excessive.

It’s a statistical error to now assume that Polymarket predicts elections better than Metaculus or Nate Silver. In fact, as Scott Alexander explains in his newsletter, applying Bayes’ theorem, one’s judgment about the relative accuracy of Polymarket, Metaculus, and Nate Silver should hardly change after Trump’s victory. Why? Because 60% and 50% are very similar predictions!

Here’s an example for those more mathematically inclined: let’s say that a week ago you were 70% sure that Polymarket was misaligned and Metaculus was correct (i.e., Trump’s probability was 50%). Now, knowing Trump won, you should adjust your confidence to 66%. In other words, you update your belief, but only slightly. Similarly, if you were 70% certain a week ago that Polymarket was more accurate (giving Trump a 60% chance), now you should update your confidence to 74%. But you’re still not overly confident! It’s a common cognitive bias to confirm our beliefs after a success, but this simple principle of probability shows that the updates should be modest.

There’s another key point: markets like Polymarket are heavily influenced by polls. They’re not really alternatives. If all polls disappeared, prediction markets would likely perform worse because they’d have lost a source of information. The evidence for this is clear — whenever a surprising or relevant poll was published, Polymarket’s numbers shifted accordingly.

6. The polling error was not large, but it is problematic

The polling error in the 2024 election was normal. Nationally, polls showed a 1-point lead for Harris, so the margin of error for her was around 2.5 to 3 points. Is that a little or a lot? It is basically a typical error. Between 1984 and 2012, the margin of error was 2 points on average. For example, in 1984, 2012, and even in 2016, the average polling error was around 2 points. In 2020, despite predicting Biden’s win, polls were off by 4.5 points. And the polls in the swing states? In 2024, it seems that the average error will be 2.5 or 3 points, as calculated by The Economist, which is an improvement from the average error of 4.2 points since 1976.

But U.S. polls do have a problem. In the past three presidential elections (2016, 2020, and 2024), polls have consistently underestimated Trump’s support. This pattern is troubling, especially because the error this year was not isolated to a few states but was apparent in almost every one, suggesting that the problem is not just random but structural. Pollsters can defend themselves by pointing to their success in the 2022 midterms, where they correctly predicted the underperformance of Republicans. But this isn’t enough to dismiss the concerns. The bigger question remains: why do polls consistently underestimate Trump’s support?

Then there are more glaring errors. Renowned pollster Ann Selzer caused a stir last week with her final poll in Iowa — her specialty — which gave Harris a 3-point victory. In the end, Trump won that state by 13 points. That is not a normal error — it was a significant failure that calls into question her methods.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.