Minneapolis: One city, three monuments against police brutality in the United States

The sites where federal agents killed Alex Pretti and Renee Good join the memorial that still stands, almost six years later, in honor of George Floyd

Atlanta photographer Ryan Vizzion has spent five and a half years on the road documenting “what kind of country America is in these turbulent times.” The day an ICE agent shot and killed Renee Good, a 37-year-old poet protesting Donald Trump’s immigration enforcement actions in Minneapolis, Vizzion was about three hours away. He didn’t hesitate: he hopped into his white van, a battered vehicle that says “Press” on one side, and headed to the scene of the crime.

Nearly 20 days later, it’s still parked across from the site of the tragedy. Upon arriving, he wondered what he could contribute to a city in crisis and decided to stay and tend to the makeshift shrine that residents erected in Good’s memory at the exact spot where her car came to a stop after she was shot a short distance away. “When you’re a journalist, you often work in a community, but rarely with it,” Vizzions explained last Sunday, next to the fire that keeps him warm each day in the open air, where temperatures can drop to minus 25 degrees Celsius.

He removes the snow when it falls, replaces the flowers less frequently than he would have thought (“it’s not that they’re dead, they’re frozen,” he says), and ensures the peace and quiet of those who come to pay their respects. It’s a haunting place; a point on the map with three stops on a journey through police brutality in the United States, which has been particularly devastating in Minneapolis.

The other two are the monuments in memory of African American George Floyd — whom a white police officer in the city suffocated with his knee while the victim repeated: “I can’t breathe” — and that of Alex Pretti, the most recent of all.

Pretti, a 37-year-old intensive care nurse with no criminal record, was filming the arrest of a woman last Saturday when he was subdued by a group of uniformed officers and shot a dozen times in the back while disarmed of the 9mm pistol he was legally carrying. It happened on Nicolett Avenue, one of the main thoroughfares of a city that today feels like a pressure cooker, constantly whistling but never quite exploding. Within hours, a new shrine had sprung up on that sidewalk, across from a popular donut shop.

Sisters Etta and Ellie Draper made a pilgrimage to those three locations last Sunday, a day that Etta described as “especially difficult” because of the place where Floyd was killed, a citizen whose memory remains alive almost six years later, at the entrance of the store where police officer Derek Chauvin killed him. His crime? He tried to pay for some loose cigarettes with a counterfeit bill.

Armed with a whistle

The young woman, who was carrying one of the whistles that activists use to warn that a raid is underway or to hinder the work Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and U.S. Border Patrol agents, explained that she occasionally visits the intersection between 38th and Chicago Avenue, which was renamed George Floyd Square.

It’s not a visit recommended for unsuspecting tourists. The altar is composed of portraits of the victim and mementos of others killed by police violence. There are dried and painted flowers and snow everywhere. A little further on, there are places to pick up free books and clothes and an abandoned gas station with a sign that reads: “While there are people, there will be power.”

In December, the Minneapolis City Council — a metropolis inseparable from its twin, St. Paul (they comprise the Twin Cities and have a combined population of 3.7 million) — finally approved a plan to “memorialize the area,” which includes four roundabouts punctuated by sculptures that resemble a raised fist. The idea was to begin construction in 2026, but the Trump administration has sidelined the project. And it remains to be seen — as the sixth anniversary of the riots that erupted in the city approaches — what will become of the site where the police station stood, the one that protesters set ablaze during those days at the end of May 2020. These were the protests that later spread throughout the U.S. as part of the Black Lives Matter movement.

There is a thread that connects that uprising with the one unfolding in Minneapolis now to halt the authoritarian drift of the U.S. president. The current protests draw on the communication infrastructure and connections forged back then, and many in these streets see the deaths of Floyd and Good as two sides of the same coin, even though the profiles of the two victims — the down-on-his-luck Black man who worked as a security guard and the white poet and mother of three — are very different.

The places of tribute to Floyd and Good are not far apart, but traveling the distance that separates them is like traveling between two worlds: from the depressed neighborhood whose residents complain that when the eyes of the world stopped looking, the same old drug and insecurity problems returned, to one of those residential streets of single-family homes in the great American suburb where there is only one perfect crime possible: killing time.

At Good’s shrine, a Mexican flag flies from a post. On another, someone has written and posted one of her cryptic poems in front of a house cordoned off with yellow police tape. It’s titled “On Learning to Dissect Pig Fetuses” and begins: “I want back my rocking chairs,/ the solipsistic sunsets/ and the sounds of the jungle, tercets of cicadas/ and pentameters of cockroaches’ hairy legs.”

On Sunday, a large white man named Mike excitedly recounted that it was his first time participating in a protest, and that when he and his wife left home that morning, they had told their children they might not return, but that they felt they “had to do it.” “I see the deaths of Good and Pretti and I can’t help but think it could have happened to me,” he explained.

Two weeks after the tragedy, the atmosphere in that place is somber. On the avenue where Pretti died, the pain is, just three days later, much more palpable. People are crying, and others are raising their voices to express their anger. On Monday, Democratic Congressman Ro Khanna (California) appeared there to tell anyone who would listen about his plans to pass a law limiting the power and funding of ICE. “We have to stop these people; they are completely out of control,” he explained to EL PAÍS.

The following day, a Spanish woman named Ana Caso, a resident of Los Angeles but visiting family in Minneapolis, came to pay her respects to someone who, she said, “gave his life” to “defend immigrants” like herself, a dual-citizenship holder. She has been afraid to go out these past few days, and when she has, it has always been with her U.S. passport. “If we don’t do something, we will lose democracy, and not only in the United States,” she said.

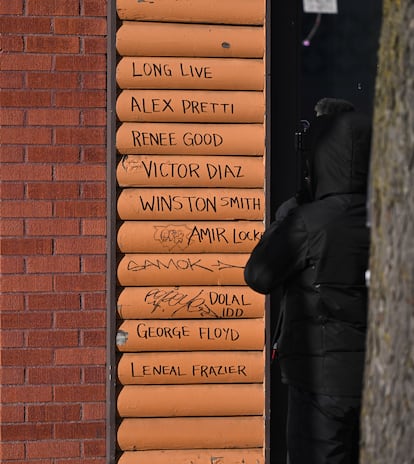

It’s still too early to know what will become of that place, or whether the commercial life of the avenue will eventually erase the memory of Pretti’s violent death. Behind the shrine, which is presided over by a photo of the victim dressed as a nurse with a contagious smile, someone has written a list of names in permanent ink, perhaps to combat oblivion.

The list includes Floyd and Good, but also Víctor Díaz, a Nicaraguan citizen killed this month in Texas while in ICE custody; Winston Smith, a young African American man shot by police in 2021; and Amir Locke, another young Black man killed when officers entered his home the following year without a warrant. They all share the fact that they were residents of the Twin Cities. They also share the fact that there is no memorial to commemorate them.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.