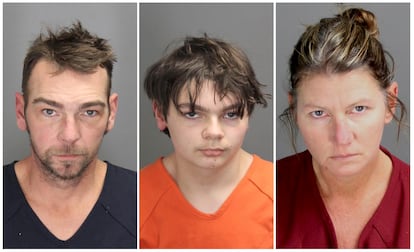

The Crumbleys, a family behind bars: The massacre that made history and landed the killer’s parents in jail

The verdict against the parents, who ignored their 15-year-old son’s calls for help and gave him a gun that he used to kill four students in Michigan, sets a legal precedent that has experts worried

Accurate Range in Jackson, Michigan, is a family business where minors are welcome; U.S. federal law prohibits them from owning a weapon, but not from practicing using one in a shooting range like this one. On November 27, 2021, Ethan Crumbley, then 15, walked with his mother, Jennifer, into one of the shooting galleries. It was Thanksgiving weekend, and they wanted to test out the SIG Sauer SP2022 9mm pistol that his father, James, had just bought Ethan. It was his early Christmas present.

Mother and son used up only half of the 100 bullets they were sold that morning. Three days later, the 15-year-old took the gun and the remaining ammunition, hidden in his backpack, into his high school in Oxford, north of Detroit. He killed four of his classmates — four students between 14 and 17 years old — and wounded seven others. Today, the entire family is behind bars. Ethan is sentenced to life in prison with no parole. His parents are awaiting sentencing: they were found guilty in two separate trials of four counts of involuntary manslaughter, one for each of the victims. They are both facing a maximum of 15 years in prison.

The conviction of Jennifer and James Crumbley — the first against the parents of the perpetrator of a firearm massacre — has been described as “historic” in the United States. It sets a precedent that could open a new era of parental responsibility for the harm caused by their children. It has also given rise to an interesting legal debate, pitting the outrage of a community gripped by tragedy and the urgent need to find ways to address the gun violence epidemic against an argument that sums up a classic maxim among lawyers in this country: “Hard cases make bad law.” In other words: To what extent is it a good idea to follow the jurisprudence of a case with as many exceptionalities as the Oxford high school massacre?

These particularities were evident during the trials. In them, Democratic prosecutor Jennifer McDonald, a former teacher and mother of five, kept her personal promise — made a few days after the tragedy — to hold the Crumbleys accountable. McDonald convinced a jury that the parents ignored signs that Ethan was suffering from mental health problems: he enjoyed decapitating baby birds in the backyard and sent distress texts to his mother warning that he felt the family home was “haunted.” Jennifer — who was presented as a woman absorbed in an extramarital affair and the care of her two horses — responded to these texts with jokes and sarcasm. There is an entry in Ethan’s diary that says, “I want help but my parents don’t listen to me.” In another, he fantasizes about using the 9mm to “maximize the number of kills.”

Not only did his parents not take Ethan to the doctor (perhaps because the cost was not covered by insurance), his father bought him a gun, which the teenager bragged about on Instagram. He posted a photo of the weapon, with a message that has gone down in the history of gun violence infamy: “Just got my new beauty today.” The following Monday, a teacher caught him looking at bullet ads in class, and the school administration notified his parents. The indictment — a horror story with American Gothic overtones — includes the text exchange between mother and son that followed the meeting. It ends with the mother telling Ethan: “Lol, I’m not mad you have to learn not to get caught.”

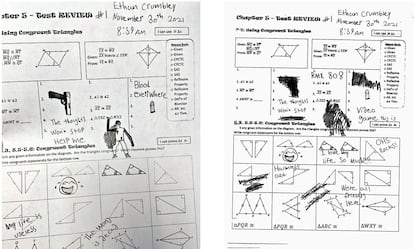

But the most serious incident happened the day of the shooting. In his school exercise book, Ethan drew a man wounded by a gunshot, a bullet with the phrase “blood everywhere” and a gun. Next to it, he wrote: “The thoughts won’t stop. Help me.” The school called the Crumbleys to a meeting but they decided that it was not worth taking the boy home; They also did not check his backpack or warn the school about his Christmas gift. Later that day, Ethan entered the bathroom, took out the gun and shot whoever he found in the hallways.

When alarms began to go off on cell phones in the quiet community of Oxford in the early afternoon, Jennifer sent her son a text: “Ethan, don’t do it.” The father, for his part, ran to check what he had feared: the gun was not in the unlocked box where it was being kept. He called the police to warn that the shooter — still active at that time — was his son. Investigators later discovered that the 9mm came from the factory with a lock that was never taken out of its plastic bag. In the following hours, they emptied their accounts and left town. They said later they fled to avoid the harassment of the media and the anger of their neighbors. Police found them four days later in Detroit. And that was another of the prosecution’s arguments: What kind of people abandon their child at a time like this?

Given the devastating story, public opinion and gun control associations have welcomed the guilty verdict against the Crumbleys. Mark Barden, who founded Sandy Hook Promise after losing his son Daniel in 2012 in the school massacre in Newtown (Connecticut) in which 22 people died, says that the shooting in Michigan is “a tragedy that could have been avoided.” “Parents and gun owners have a responsibility to prevent access to minors, and that is what these rulings underscore,” says Nick Suplina, vice president of Everytown for Gun Safety. Barden also hopes that Ethan’s case will help change gun law. In Michigan, it already has: the state has since passed a CAP law that requires adults to lock up their guns.

Morally guilty

In the field of law, the verdict has been less unanimously welcomed. While there is consensus that the Prosecutor’s Office presented convincing arguments to find the Crumbleys morally guilty, there are also doubts about the contradiction of deciding to prosecute Ethan as an adult in order to apply the maximum sentence while also holding his parents responsible. But above all else, there is concern about how the newly established precedent may be applied.

“The first thing you teach criminal law students is that when a responsible agent acts, you cannot be responsible. Also, that sometimes the law changes. And this is one of those times,” explains Ekow N. Yankah, a professor at the University of Michigan and an expert in legal philosophy. “If I wanted to test them on this principle of law, I could not have written a more painful exam than this actual truth. And we have to give the prosecutor credit that 12 people twice over — 24 people — listened to the facts of this case and agreed that they’re responsible for what they did, or more importantly, what they didn’t do. If I am completely honest, I don’t know what I would have ruled in the jury box.”

Technically, the verdict against the Crumleys sets a precedent that only applies in Michigan, but there is nothing stopping a lawyer in Indiana or Ohio from using it. “Precedents create laws, and if they have one, prosecutors use it,” warns Yankah. “Granting prosecutors more powers to prosecute more people is not a good idea, especially in the United States, where it is estimated that 95% of cases never go to trial, they just get pled out.” “Suppose,” the expert continues, “that a father who did not suspect that his son was about to do something terrible is told: ‘If you accept three years in prison, I will not take you to trial.’ If not, you could be given 15.′ It is very likely that many will sign such a deal out of fear. That is why precedents can be very powerful in ways that are invisible to us. Those cases will not get in the news.”

Evan Bernick, a law professor at Northern Illinois University, believes that the next time there is a mass shooting at a school, the prosecutor will want to use the Crumbley precedent to address the community’s indignation. “But it is one thing for it to be limited to killings with firearms and quite another for it to extend to any type of intentional crime,” he adds.

Both experts gave similar examples to illustrate their fears. If a child joins a gang and murders someone or a wayward teenager carries out an armed robbery: could the mother or father be convicted for not having been aware that they were drifting into crime? An affirmative answer to that question, Bernick fears, would not only worsen America’s mass incarceration crisis; it would also take an especially hard toll on minorities, in particular the Black population. “I’m worried about negative stereotypes about Black parents being irresponsible mixing with the idea that black kids are more adults and more intentional in their actions,” he explains.

In his influential book Far from the Tree (2012), psychiatrist and writer Andrew Solomon reflected on the saying “The apple does not fall far from the tree,” when it comes to raising children with problems. In one of the most famous passages of that monumental book, he gave voice for the first time to the Klebolds, who one day in 1999 woke up, horrified, realizing that their 17-year-old son, Dylan, had become a “monster”: Dylan and his friend had murdered 12 students and a teacher at Columbine High School before killing themselves. In the book, Sue Klebold says: “I know it would have been better for the world if Dylan had never been born. But I believe it would not have been better for me.”

In an email, Solomon this week called the Crumbleys’ conviction “part of a larger strategy in which we accuse everyone and everything but the NRA lobbyists who have kept civilian possession of firearms as a norm.” “Where guns are not legal, there are almost never school shootings. The Crumbleys are part of a larger American establishment that has normalized gun ownership. If they prosecuted everyone with an unlocked gun and every teenager who has complained about mental health but not received treatment, you’d arrest 15% of American parents,” he says. “The Crumbleys seem pretty awful from their court experiences; they were clearly neglectful. But if we are to imprison them, we are pointing to a failed society that needs to be revamped to care for those who say, ‘My life is worthless’ and not only for those they end up murdering.”

The example of Columbine is relevant. The murderers were minors, and that school massacre — which at the time was the deadliest in the history of the United States — was not only burned into the national imagination (thanks to the Michael Moore documentary and a disturbing fictional reconstruction by Gus Van Sant), but ushered in the modern era of mass shootings, especially in schools.

School shootings

Between 2000, the year after Columbine, and 2022, there were 1,375 school shootings, according to data from the Department of Education. In the last five years, there were more school massacres than in all previous years combined, partly because the number skyrocketed after the pandemic. Of the 10 most serious gun massacres in North American history, two occurred in elementary schools, Sandy Hook (26 victims), and Uvalde, Texas, where 19 children and two teachers were killed in 2022. In both cases, the shooters were white males under 21 years of age, an increasingly common profile: since 2018, this profile was involved in seven of the 10 mass shootings with the highest number of victims in the United States.

After each of these tragedies, a barrage of civil lawsuits against the schools and the parents of the murderers — 36, in the case of the Klebolds, 16 against the mother of the Sandy Hook killer —, typically follows. But until now, none of the parents had ever been criminally convicted. When asked what cases the Crumbley precedent could be applied to retrospectively, Yankah cited another infamous massacre: the shooting at the Fourth of July parade in Highland Park (Illinois) in 2022, when a 19-year-old murdered seven people chosen at random. To avoid criminal prosecution, his father pleaded guilty to signing the authorization his son needed to purchase the gun that was used in the massacre. The precedent could not apply to parents of the Columbine killers, says Yankah, explaining that the perpetrators planned the massacre for months. “In such deliberate behavior, it is almost impossible to convict anyone who wasn’t in on the plot,” he explains.

After breaking her silence in Solomon’s essay, which describes the Klebolds as a couple who tried to do what they could to help their son, Sue Klebold decided to tell her story in the haunting book A Mother’s Reckoning: Living in the Aftermath of Tragedy. In it, Klebold — who did not respond to this newspaper’s request for an interview — includes a letter sent to her by the father of a student at Columbine High School, one of Dylan’s victims: “What signs of hatred and despair did you see? What warning signs did you miss? Were you a family that ever spent much time at the dinner table together? What did your son talk about? What would you have done differently in raising Dylan? […] Your son was so angry and distressed and hateful and so troubled that he wanted to kill hundreds of his classmates. Hundreds! How in the world could you not have seen that your son was THAT hateful and troubled? How did you become so disconnected that you did not see this disposition of his? How could that happen?!?”

The answer to those questions could lie in a 2015 FBI report that offers clues on how to prevent tragedies like the Oxford High School shooting. “In many circumstances,” it reads, “parents have the best optics on a person of concern’s struggles and vulnerabilities,” but they prefer not to see the warning signs or they minimize them. Lost among its 129 pages, there is also a sentence that seems to be written with the Crumbleys in mind: “Irresponsible and chaotic families can also contribute to casual access to firearms in the home.” On April 9, the Crumbleys will find out what this negligence will cost them. Their respective sentences could add up to 30 years in prison.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.