Dearborn: The Arab heart of the United States is abandoning Biden over the war on Gaza

‘He would have to become Jesus himself and resurrect the 20,000 dead Palestinians to get our vote back,’ say residents of the seventh-largest city in Michigan, which has the highest concentration of Arabs in the country. They are standing against the president’s 2024 re-election campaign

Adam Abusalah, a 23-year-old Palestinian-American community activist, is outraged. He makes his feelings clear while chatting with EL PAÍS in a restaurant in the heart of downtown Dearborn, Michigan. He arrives adorned with a kufiya, a traditional Palestinian black-and-white scarf. He greets other customers in English, in the Palestinian Arabic dialect, or in a mixture of both. “I worked on Biden’s presidential campaign in 2020. Then, I was in charge of mobilizing the Arab-American vote in his favor, getting people to register to vote and support him. And now, after having helped him get to the White House, I feel like he’s helping to bomb my family in Palestine… I feel betrayed.” This young Palestinian-American — who has been involved in politics his entire adult life — swears that he will never support Biden again. “Even if my ballot decided the election between him and Donald Trump, I wouldn’t vote for him,” Abusalah vows.

He’s not the only one who feels this way in Dearborn. This industrial city — the seventh-largest in the state of Michigan, next to Detroit — is nicknamed the “Arab capital” of the United States. More than half of its residents — 54.5%, according to the last census — are of Middle Eastern or North African origin. They heavily voted for the Democratic Party in the 2020 presidential elections. Their support made it possible for Biden to win Michigan, a crucial swing state. However, since the beginning of the war on Gaza — and given the unconditional support of the President of the United States for Israel — many residents have declared themselves to be totally opposed to a second mandate for the current occupant of the White House. From Dearborn, a campaign has started to ensure that no Arab-American supports Biden’s re-election in November 2024.

“We want to link his presidency to Gaza. Let it be one of the factors that causes his defeat. Let the history books and Civic Education classes reflect that Gaza cost Joe Biden the presidency,” says Khalid Turaani, 57, from the Michigan Task Force for Palestine. He’s one of the participants in the #AbandonBiden campaign.

Palestinian flags and inflatable reindeer

Dearborn is a deeply American-looking city. A center of automobile production in the United States since Ford moved its factories here in the 1960s, this town of 108,000 inhabitants is, at first glance, indistinguishable from so many others. Residential neighborhoods coexist along seemingly endless straight avenues. There are mostly single-family homes with various roadside shopping centers.

But here, in these malls, the franchises that are ubiquitous in the rest of the country rub shoulders with hookah cafés, Levantine bakeries and travel agencies offering flights to Yemen. The signs on the establishments are written in English and Arabic. Mayor Abdullah Hammoud is of Lebanese origin, like Police Chief Issa Shahin.

In downtown Dearborn, Palestinian flags in gardens and windows coexist with Christmas lights and inflatable reindeer. Mosques — adorned with huge American flags — alternate with churches. In front of the Modern Hijab boutique — which offers traditional women’s clothing in modern colors — a nativity scene on the street invites passersby to celebrate the birth of Jesus.

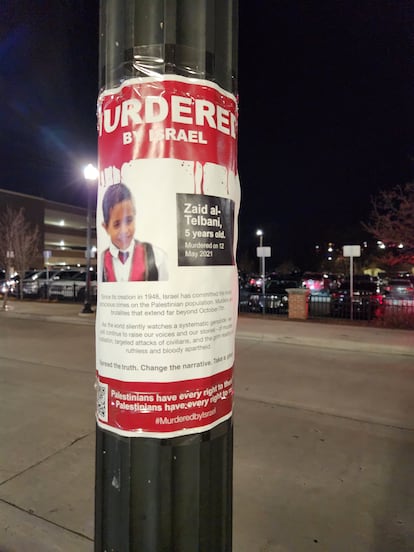

On some of the main streets, posters display photos of some of the nearly 10,000 Palestinian children who have been killed by Israeli airstrikes on Gaza. These imitate the red-and-white posters with images of Israeli hostages captured by Hamas, which have been put up in Western capitals since the October 7 attacks.

Here, the war on Gaza — in which Israeli attacks have already killed more than 20,000 Palestinians, with thousands more declared “missing” — has hit especially hard. Anyone who does not have family in the Strip knows someone who has lost loved ones there. Fewer people are out and about: there’s palpable fear of the Islamophobic attacks that have increased since the beginning of the bombardment of Gaza. Residents remember the murder of a six-year-old Palestinian child in the state of Illinois this past October, when he was stabbed to death by his family’s landlord. Or they recall the shooting of three Palestinian-American students on Thanksgiving Day in Vermont. The mood is somber. In casual conversations in bakeries and restaurants, words like “Hezbollah,” “war,” and “Palestine” are constantly heard.

Dearborn is outraged that the U.S. government refuses to call for a ceasefire, even after other pro-Israel governments — such as the British or German governments — have shifted their position. Residents are angered by military and financial aid to the Israeli government: they are angry that Washington approved a new shipment of weapons and bombs to the Israeli military immediately after vetoing a U.N. Security Council resolution calling for a ceasefire. The recent censure against the only representative of Palestinian origin in the U.S. Congress — Rashida Tlaib — is cited as an attempt to silence pro-Arab voices in public life.

Although Arab-Americans in Michigan have always been politically active since the early 20th century, when members of the community first settled in the state, “the nature and breadth of political activity now seen in Dearborn is something new,” explains historian Sally Howell, a professor at the Center for Arab American Studies at the University of Michigan-Dearborn. “It’s new because the community has never gone through a political crisis like this with so many legislators — such as Rashida Tlaib or Abdullah Hammoud — representing them. The political gains that the population had made in their decades of hard work at the local or state level seemed to have assured them a seat at the table, but the assault on Gaza and the American government’s support [for the Israelis] has shown how little Arab-American voices matter on an issue so fundamental to their lives and their values.”

At the same time, Howell adds, “there’s an unprecedented assault on freedom of expression against those who are critical of the Israeli aggression. The media does not report neutrally about what’s happening on the ground in Israel and Gaza. Anti-Arab racism and Islamophobia are skyrocketing. These realities are motivating all kinds of new forms of political protest and solidarity.” Despite the fact that Dearborn is very diverse — with both fourth-generation Americans and newcomers, Democrats and Republicans, Iraqis and Lebanese, Yemenis and Palestinians — as far as Palestine is concerned, the expert maintains, “the community speaks with one voice.”

This community’s rejection of the White House could be fundamental in the outcome of next November’s elections. In 2020, Biden defeated Trump in Michigan by just 154,000 votes, or 2.5%. And, in the state, 300,000 registered voters are of Arab ancestry. In the election three years ago, about 146,000 of them voted, with nearly 70% of them supporting the Democratic ticket. The blow to the president’s political prospects could be greater if — as the #AbandonBiden organizers propose — Arab-American communities also turn their backs on the president in other swing states where they have critical power, such as Georgia, Virginia, or Minnesota (which all went Democratic by narrow margins in 2020).

An Arab American Institute poll released on October 31 found that support for Biden among Arab-American voters fell from 59% three years ago to 17% — a decline of 42 percentage points. Two-thirds of that electoral group had a poor opinion of how Biden has managed the United States’ role in the conflict. The survey was conducted more than seven weeks ago — the situation in Gaza has only become more catastrophic since.

This state of opinion adds to Biden’s overall troubles in the polls, which place him behind Trump. His approval rating has fallen to 37%. This week, a poll by Siena College for The New York Times indicated that 57% of Americans surveyed disapprove of the president’s management of the conflict, while only 33% support it. The most critical of Biden are the youngest voters (18-25), who are overwhelmingly pro-Palestinian.

Arab disenchantment with the president threatens to spread to other Democratic candidates as well. Congresswoman Elissa Slotkin — a Michigan Senate candidate next year — “has expressed concern to her allies that she may be unable to win her election” if Biden remains as the party’s presidential candidate, according to a report by The Washington Post that was published this week.

“It’s not just Joe Biden. We’re not going to vote for anyone who has shown disinterest in Palestinian lives. For anyone who has not spoken up. If you fear the Israeli lobby enough to not denounce injustices, don’t count on us,” warns Adam Abusalah, the young activist.

The White House maintains, for its part, that it’s putting pressure on the Israeli government to moderate its tactics. National Security Council spokesman John Kirby has claimed that no country “has done as much to alleviate the suffering of people in Gaza as the United States.” Wary of the unrest among Arab voters, the White House has organized meetings with community leaders. These have not swayed the population.

“We will not vote for Biden”

Osama Siblani, 68, came to the United States from Lebanon in 1976, fleeing the civil war in his country. He has always been interested in politics. He founded and co-chaired the lobbying group American Arab Political Action Committee (AAPAC) and accompanied Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) leader Yasser Arafat in signing the Oslo Accords. He established the largest newspaper in the Arab community in the U.S. — The Arab American News — in 1984. It has a weekly circulation of 35,000 print copies, along with a strong online presence. In a conversation with EL PAÍS in his office, he is blunt: “We will not vote for Biden.”

Siblani — who will be leaving his presidential ballot blank next November — assures this newspaper that, in 2020, the Biden campaign promised to give a cabinet position to an Arab-American. “But we don’t have a cabinet secretary, nor even a deputy,” he laments. “He won thanks to our votes. But let me assure you: in the next election, we Arab-Americans will not vote for him.” The rejection, he maintains, is immovable. “To recover our vote, Biden would have to become Jesus himself and resurrect the 20,000 dead Palestinians.”

The pressure applied by this community also extends to the judicial sphere. In his office in downtown Detroit, attorney Nabih Ayad has framed newspaper clippings of his most famous cases. When the invasion of Iraq began in 2003, he sued the U.S. government. In 2017, he appealed against the entry ban (colloquially known as the “Muslim ban”) that then-President Trump imposed on citizens of countries he classified as “shitholes,” most of them Arab-majority nations. Since the start of the war, Ayad has focused his efforts on getting the Biden administration to facilitate the evacuation of Palestinian-Americans remaining in Gaza. He has pointed out the discrimination against those citizens, when compared to evacuation operations for Israeli-Americans.

“We have 50 volunteer lawyers. We have filed lawsuits in 22 states. The idea is to apply pressure. And [the American government] has finally started compiling a list [of evacuees]. But they can do much more: Israel is supposed to be their most faithful ally. They can call them and ask them to stop bombing, ask them to establish a way for Palestinian-Americans to leave,” he explains.

Not everyone in Dearborn shares those critical views. At the University of Michigan-Dearborn, international relations student Vincent Intrieri says the issue has driven a deep wedge between students. He himself attended two pro-Gaza demonstrations and maintains he will no longer do so, weary of what he sees as a whitewashing of Hamas among some of the students. “You can be right, but if you attack children, women, that’s terrorism. And if you practice terrorism, that will taint your whole community... Hamas is a terrorist group and you can’t excuse what they did.” On Biden, and the proposals not to vote for him, Intrieri is skeptical. “It’s true that Biden hasn’t taken very strong action, but it’s also true that his hands are tied.”

Adam Abusalah, the young activist, emphasizes that the vote against Biden “is a short-term harm, but a benefit in the long run.” “If Trump wins, we’ll suffer for four years. But people are going to realize that, to win an election, they have to win over the Arab-American community in Michigan.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.