Colorado: Lessons from a sanctuary state for abortion in the US

In this corner of the West, some of the most progressive laws in the country have been passed in response to the Supreme Court ruling that struck down ‘Roe vs Wade.’ It is the fruit of years of work by activists and Democratic politicians

The alarm that shook activist Aurea Bolaños Perea into action was the Texas Heartbeat Act, which was passed in September 2021. Mirroring many rules that would follow, it banned abortions as early as six weeks of pregnancy, when most women do not yet know they are pregnant.

This was nine months before the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe vs Wade, the landmark ruling that established the constitutional right to abortion in 1973. Texas’ proximity to Colorado — the states share a border with Oklahoma, which followed with a similar abortion ban — prompted Bolaños Perea, along with other activists and lawyers, to ask what legal safeguards protected reproductive freedom in Colorado. “The answer was: none,” she told EL PAÍS from an office in downtown Denver.

The organization she works for, Color Latina — which was born as a response to the AIDS epidemic and been defending the “reproductive rights” of the Latino community for 25 years — began working with other groups on a law to protect reproductive rights. The goal was to have a law in place before the Supreme Court issued its expected ruling on the federal right to abortion (the draft opinion was leaked in May 2022). As a result of those efforts, the Denver Capitol passed the Reproductive Health Equity Act, which recognizes the fundamental right to abortion and contraception. Colorado is also one of seven states without any term restrictions as to when a pregnancy can be terminated.

But the work did not end there, and during the last legislature, which ended last May, the Democratic-majority Congress in Colorado passed a package of regulations that goes even further, making it one of the most progressive places in the country, along with California, neighboring New Mexico and Massachusetts. In the meantime, at least 21 states have banned or severely restricted access to abortion since the Supreme Court ruling last year.

The Colorado legislative package made up of three laws. The first protects doctors who provide abortion care or gender-affirming care from being prosecuted by states such as Oklahoma, Mississippi and Texas, where offenders face sentences of up to life in prison. It also exempts Colorado police from cooperating in such criminal investigations. The second law requires commercial insurance providers to cover abortions for patients without copays (with the exception of public employees). And the third, promoted by Color Latina and another organization called New Era Colorado, prohibits “fake” anti-abortion clinics from advertising or offering pills to reverse abortions, explains Bolaños Perea. According to the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, such promises are “not based on science.”

Bolaños Perea says that Color Latina set out to address these clinics when they began to flood billboards, radio stations and newspapers with Spanish-language ads. “They also buy search terms so that when you put in ‘abortion,’ ‘young,’ and ‘Colorado,’ one of those pseudo-centers comes up first. The Latino community is one of the most affected by these tricks,” she said. During the parliamentary debate, doctors and activists spoke about how pregnant women are misled into believing they have an appointment with a doctor, only to find themselves at a pseudo-clinic that tries to talk them out of having an abortion, offers to throw them baby showers and gives them ultrasound images of fetuses at more advanced stages.

Planned Parenthood, which manages around half of the abortion clinics in the country, was committed to promoting the law that protects doctors and nurses from criminal prosecution. Specifically, its subsidiary in the Rocky Mountains (PPRM), which operates in Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada and Wyoming, a state controlled by Republicans where there are no Planned Parenthood centers.

Adrienne Mansanares, PPRM executive director, tells EL PAÍS that the number of patients in Colorado has risen 33%. “Women suddenly turned into immigrants wandering the roads of their own country,” said Mansanares, who said the numbers have been rising since the Texas Heartbeat Act. To address the rise, the centers have more staff and expanded their opening hours. Support networks for patients arriving from other states have also been strengthened since the Supreme Court ruling: the map of Colorado is a perfect rectangle surrounded on three sides by anti-abortion bastions. “Some women have never been on a plane before coming here. Others do not have a credit card to check into the hotel. And most have families, and have to bring their children. We give them vouchers for food or money for gas,” said Mansanares.

The Colorado law does not protect patients from what may happen to them when they return home. For this reason, at the PPRM center in East Denver, a woman from Texas arrived one day after driving for 17 hours and decided to leave her cellphone at home, to avoid being tracked. “It is incomprehensible that something like this can happen. Sometimes I wonder if we really live in the United States in 2023,” said Jack Teter, PPRM’s regional director of government affairs, in one of the meeting rooms of the clinic.

Teter, who was active in the legislative process, estimates that the average commute for patients from outside of Colorado is 650 miles. “That is why it was so important to create an oasis of freedom, with the most advanced laws in the country, while the regressive wave grew around us. It was not only necessary to guarantee that abortion would be legal, but also accessible to everyone.” Mansanares said that the passage of these laws was the result of “years of pedagogical work” and investment in promoting candidates who support reproductive freedom.

Backlash

When the package of laws was passed, Colorado House Republican Leader Mike Lynch said they would turn the state into a destination for “the vulnerable, the indigent and frightened minors from all over the country.” “They deny a new mother the choice to consider alternative options other than to end her pregnancy.”

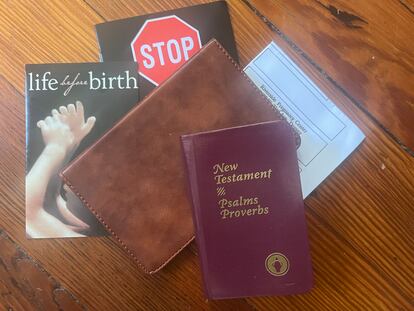

At the gates of the PPRM clinic, three men and a woman were waiting to intercept any woman who tried to go in. One of them, Mike (he did not want to give his last name) said that he spends the day there because “inside they kill babies from Tuesday to Saturday.” Bill Merritt, a retired pastor, also said he was often on the street. He hands out bags with two pocket books, a summary of the Gospels, a compendium of psalms and proverbs from the New Testament, and pamphlets with the contact information of the pseudo-centers, who are now prohibited from posting publicity. Merritt recalled that Colorado “wasn’t always like this.” “All of this is the result of a change in a state that has become increasingly liberal,” he warned.

The unprecedented change in Colorado is only partly explained by the state’s changing and increasingly younger demographic. In The Blueprint, Rob Witwer, a former Republican member of the Colorado House of Representatives, and journalist Adam Schrager, try to explain how Colorado went from being a Republican stronghold in 2004 to a Democratic bastion in just four years. Democrats have controlled the state since 2008. Before then, the state had voted for a Republican president every year since 1964, with the exception of Bill Clinton, in 1992.

Before that, Teter recalls, the state was famous for being the headquarters of the Christian organization Focus on the Family (it still exists, in Colorado Springs)and for approving a constitutional amendment in 1992 that prevented municipalities from enacting anti-discrimination laws protecting LGBTQ+ people (it was later overturned by the Supreme Court.

“In the national press they called it the State of Hate,” said Teter. In 2015, he became the first transgender person to work at the Denver Capitol. “I couldn’t imagine then that eight years later a law would be approved there that would protect, in addition to the right to abortion, gender-affirming care,” he added.

One of the protagonists of The Blueprint is Jared Polis, an internet entrepreneur his 20s, who decided to apply the laws of business to his effort to turn Colorado into a liberal state. Today, Polis is 48 years old and the governor of Colorado. He is also the first openly gay governor in the United States. Last April, he triumphantly signed the package of three laws before a large group of Democratic politicians and activists, mostly women. Among them was Senator Julie Gonzales, who celebrated the achievement with an address to all women: “We see you and in Colorado, we’ve got your back.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.