The 599 redacted lines threatening Trump

The recently released affidavit justifying the search of the former president’s Mar-a-Lago residence raises the question of whether he will face criminal charges and when

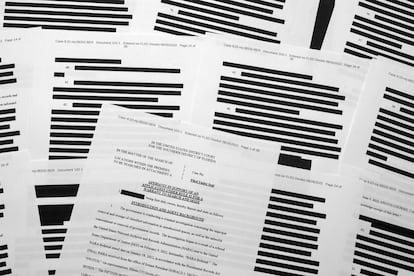

No US president has been charged with crimes after leaving office. Richard Nixon came close over the Watergate case, but, his successor, Gerald Ford, pardoned him in an unpopular decision that contributed to his losing the 1976 elections against Jimmy Carter. Now, the US Department of Justice is closing in on Donald Trump. The evidence against him is abundant. A 38-page redacted affidavit justiying a search warrant at Mar-a-Lago, his mansion in Palm Beach, was released by a judge last Friday along with other documents containing 599 lines that had been blacked out. The information that it reveals and, more importantly, what it does not, could bring the former president before a court for a variety of possible crimes.

On the afternoon of August 8, when Trump revealed that his mansion was being searched by the FBI, he wildly compared the entry to Watergate, the break-in of the Democratic National Committee headquarters. Also on August 8, but 48 years ago, Nixon was preparing his resignation speech after being cornered by the Watergate scandal.

Nixon’s reluctance to release incriminating documents and recordings of conversations was precisely what later led to the passage of the 1978 Presidential Records Act, which declares public all documents, reports, photographs, notes, and other records that the president handles during office; and obliges him to preserve and deliver them to the National Archives upon termination.

Trump never paid much attention to that norm, which is at the origin of this case. During his presidency, it is said that he tore up papers that his collaborators later collected and put back together with tape. He also allegedly flushed some of his notes down the White House toilet to dispose of them. When Trump stepped down in January 2021 in a stormy transition of power, he took dozens of boxes of presidential documents to his Mar-a-Lago mansion.

That led to a tug-of-war with the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA or the National Archives), which asked him to hand over the documents as early as May 2021, according to a statement. A former president breaking the law was an embarrassing situation, but a breach of the Presidential Records Act (PRA) as such is not a crime and so NARA had to be patient to claim what belonged to them. When the National Archives warned they would alert Congress and the Justice Department, only then did Trump agree to deliver 15 boxes, received by the Archives on January 18 of this year.

Classified documents

The Archives confirmed at the beginning of the year in a statement that the returned documentation included papers that had been torn up by the former president, some of which had been taped back together and others that remained in pieces. When examining the boxes, “a lot of classified documents” were discovered, some that hadn’t been filed properly and were mixed in with other documents, as reported to the Department of Justice on February 9. NARA also reported in a letter to Congress that it had identified classified national security information in the boxes. Trump’s committee replied that the Archives had found nothing, that they had simply received what they had asked for in a procedure described as “ordinary and routine.”

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) analyzed the boxes’ contents in detail between May 16 and 18. They found 184 classified documents, of which 67 were marked as confidential, 92 as secret, and 25 as top secret, including some with additional markings indicating highly restricted content or information about intelligence sources, the report has now revealed.

The FBI investigated and concluded that Trump had not turned over all the documents. The details of that investigation are redacted in the affidavit, but it mentions that there are a “significant number of civilian witnesses” to this claim. There was also ground surveillance and a requirement to seize Mar-a-Lago’s security camera recordings. Trump was requested to hand over any documents he still had in his possession, but following his denial, the FBI decided to request a search warrant for Mar-a-Lago.

“There is probable cause to believe that additional documents that contain classified NDI [national defense information] or that are Presidential records subject to record retention requirements currently remain at the premises. There is also probable cause to believe that evidence of obstruction will be found at the premises,” wrote an FBI special agent who signed the affidavit requesting the search warrant.

The search warrant and the inventory of seized assets, published two weeks ago, revealed that Trump is being investigated for obstruction of justice, concealment, willful removal or tampering with public documents and violations of the Espionage Act, apparently for withholding national security documents. These crimes are punishable by a fine or by prison sentences. In the search, the FBI seized 11 sets of classified material. One is classified as “top secret/sensitive information,” a further four are documents considered “top secret,” three are “secret documents” and another three are “confidential.” The list did not offer details as to the nature of the classified documents.

The redacted lines in the affidavit pertain to five types of information. The first, to “protect the safety of multiple civilian witnesses,” says a Justice Department document that explains the reasons for concealing parts of the document. “If witnesses’ identities are exposed, they could be subject to harm such as retaliation, intimidation, or harassment, and even threats to their physical safety,” he argues. Secondly, to preserve the case: “The affidavit is packed with additional details that would provide a roadmap for anyone seeking to obstruct the investigation.” Third and fourth correspond to information about the grand jury and about the agents investigating the case. And, finally, information about third parties “that could harm the interests of privacy and the reputation of these people if disclosed.” The document gives examples, but these are also crossed out.

Trump maintains that it is all a “witch hunt,” the action of “pirates and thugs” for political purposes. Together with his lawyers, he has shot out in all directions to defend himself. On the one hand, he said that he took the documents “without knowing it.” On the other, he suggested that they were “planting” evidence on him. He then argued that his predecessor, Barack Obama, had millions of documents in his possession in Chicago, which led to a resounding denial from the National Archives. His lawyers have also said that the Presidential Records Act is not criminal in nature and, therefore, does not include crimes that could justify a search. That is true, but the crimes being investigated do not fall under they purvey of that particular law.

Biden’s taunts

To varying degrees, they have tried another shaky line of defense. His lawyers noted in a letter that the president had the power to declassify any document (without claiming that he had actually declassified them). Trump later said on his social network Truth Social that “everything is declassified,” without providing any justification for it. President Biden, who until now had avoided commenting on the matter, could not contain himself last Friday and he mocked that excuse, paraphrasing Trump: “Well, I just want it to be known that I have declassified everything in the world. I’m the president, I can do it… C’mon, declassified everything?!” he said to journalists, as he waved his hands in the air.

Not only is the defense not particularly credible, in the light of so much top-secret information, but it wouldn’t be able to free him from the crimes. In a footnote on page 22 of the affidavit, an FBI agent highlights that the Espionage Act does not refer to classified documents but to “information related to National Defense.” If Trump says he declassified the documents, it is an implicit acknowledgment that he knew he had possession of them, weakening the line of defense that he was not aware of it. Trump’s lawyers asked another judge in Florida last Friday to take action on the matter. It was again revealed, that Trump had the power to declassify the documents, but they avoided saying if he did. In that brief, Trump’s lawyers complained that the published affidavit “provides almost no information that would allow the plaintiff to understand why the search took place or what was taken from his home.” The few lines that are not crossed out raise more questions than answers, they added.

An unanswered question is why Trump has repeatedly resisted handing over the documents. Even after admitting that he took them without realizing it, it is not understood why he retained them after months of requests and requirements, putting himself in such a compromising situation. It is also not known whether the suspicions of obstruction of justice, the crime with the highest penalty of those under investigation, are based only on that resistance or if there is additional evidence in this regard.

But the big question, right now is whether Attorney General Merrick Garland will take the step of pressing charges against Trump. Garland, in his only appearance in the case, has already said that decisions such as the search warrant “are not taken lightly.” But while the evidence of crimes seems solid, filing charges is a different matter and would represent another explosive step, even more significant than the previous one that has already further polarized the country and fueled worrying civil-war rhetoric. Trump could even politically capitalize on the accusation, presenting himself as a martyr, for the 2024 presidential elections, which adds more complexity to the matter. And then there’s the risk of revenge attempts in future power transitions.

Alan Dershowitz, Trump’s former lawyer, said on Friday on the conservative Fox network that “there is enough evidence to indict Trump.” “In my opinion, Trump will not be indicted because it doesn’t pass what I call the Nixon-Clinton standards,” added the now Harvard Law Professor Emeritus, referring to former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and the use of a personal email account. “The Nixon standard is, the case has to be so overwhelmingly strong that even Republicans support it. And the Clinton standard is, why is this case more serious than Clinton’s case, where there wasn’t a criminal prosecution?” Dershowitz clarified that this opinion is based on what we know so far: “Once it is not crossed out, we may have to change our mind.”

Among Trump’s multiple judicial mishaps, the Department of Justice is also currently investigating his role in the assault on Capitol Hill on January 6, 2021, and pressure to subvert the electoral result after the November 2020 elections.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.