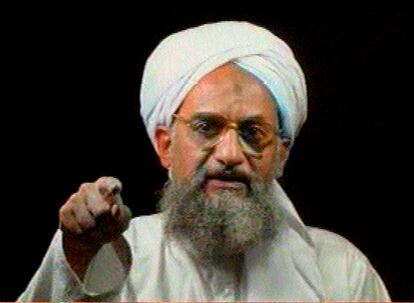

Who was Ayman al-Zawahri, Al Qaeda‘s mastermind in the shadows?

Osama Bin Laden’s lieutenant, who has just been killed by a US drone strike, lacked the charisma of his predecessor but was endowed with great ideological powers of persuasion

President Joe Biden is on a roll, after months of struggle. To his recent domestic achievements (a climate and tax plan, and his strategic challenge to China) he can now adds a feat with international repercussions: having rid the world of its most wanted terrorist: the Egyptian Ayman al-Zawahri, 71, who was killed in US a drone strike in Kabul over the weekend, the US government said on Monday.

This is similar to what Barack Obama achieved with the execution of Osama bin Laden in Abbotabad (Pakistan), on May 1, 2011. The correlation between the two Democrats comes to signify, symbolically, the end point of the organization that attacked the heart of America on September 11, 2001.

“Al Zawahiri is not charismatic. He didn’t get involved in the previous war in Afghanistan [against the Soviets] and I think he has a lot of detractors within the organization.” These were the words of US Security Adviser John Brennan a day after the fall of Bin Laden, about the man who was considered the number two within Al Qaeda. Al Zawahiri, an opaque but strong leader, did not seem to have what it took to take command of the organization. But against all odds, and after a brief interregnum by the Egyptian Saif al Adel, himself a veteran combatant in the Afghan war against the Soviets, Al Qaeda’s leadership elected Abi Mohamed Ayman al-Zawahri.

Al Zawahiri was born in 1951 in the Giza neighborhood of Cairo, into a wealthy family linked to medicine. As the writer Lawrence Wright recounts in the book The Looming Tower: Al Qaeda and the Road to 9/11, the young man followed the family tradition and in the 1980s he worked in a clinic in the wealthy Cairo neighborhood of Maadi. Al-Zawahri made his profession compatible with the study of Islam -his grandfather had been an imam of the prestigious Al Azhar mosque, a focal point of political Islamism-, thanks to the early relationship he established with the Muslim Brotherhood, an Islamist organization banned in Egypt since 1954.

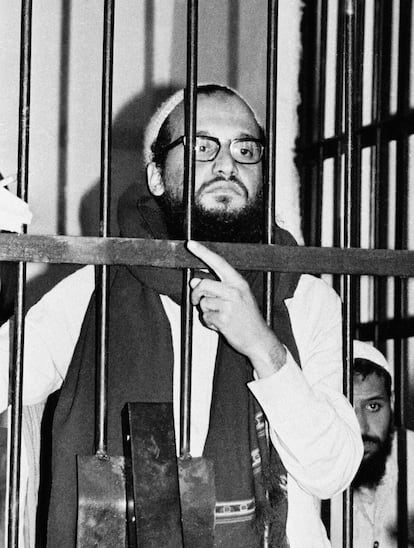

Because if Al Qaeda had a Saudi public dimension, thanks to Bin Laden’s family fortune and his populist pull, its ideological DNA was entirely Egyptian: the outpost of radical Islamism that would soon take over part of the Maghreb region (Algeria, for example). ); the doctrinal aristocracy of the new jihad. Al-Zawahri soon assumed command of the Islamic Jihad, founded in 1973 and responsible for the assassination of Anwar el Sadat in 1981 due to the peace agreement that the Egyptian president had signed with Israel.

The intellectual authorship of the attack and a three-year stay in prison were the best letters of introduction to the enlightened Saudi named Osama Bin Laden with whom he made contact in the mid-1980s in Peshawar (Pakistan). Al Zawahiri had enrolled in the Red Crescent, a tactical withdrawal that was half estrangement, half exile, to flee the harassment of the security forces in his country, which had subjugated the Islamist movement. Peshawar was the rearguard of the Jihad against the Soviet invader in Afghanistan - backed by the US and Saudi Arabia - and the place where the doctor took care of the faithful wounded combatants. The exchange between the two men was fruitful: the Egyptian became an intellectual and ideological reference, infusing doctrine into the Saudi, who was at the time the leader of a recently created organization called Al Qaeda. In 1988 both agreed to merge Al Qaeda and Islamic Jihad and a decade later, they declared “holy war against Jews and Crusaders.” Only three years later, their men brought down a symbol of Western power: the Twin Towers in New York City.

Earlier, in 1993, an alleged assassination attempt on then-Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto led to Al Zawahri’s expulsion from the country. From there he traveled to Sudan, where Bin Laden had taken refuge after being deprived of his nationality for his destabilizing activities, dangerous even for the rigorous Riyadh court. With the seizure of power by the Afghan Taliban, and the withdrawal of the Soviets, the “communist atheists” ceased to be the enemies in favor of the godless West. From Africa, the two allies began the countdown to the tragedy in New York: the attacks against the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, which caused hundreds of deaths, and which were the first example of a double suicide attack inspired by Al-Zawahri as modus operandi of the organization. After 9/11, Interpol issued a warrant for his capture as the head of Al Qaeda. Washington offered a $25 million reward.

For this reason, despite Brennan’s reluctance, Bin Laden’s right-hand man replaced him at the head of Al Qaeda, and immediately opened regional franchises, such as the Arab Maghreb (AQIM) or the Shabab from Somalia: it was an effective way to multiply the radius of action with little investment. Over time, some of these subsidiaries outgrew the lethal impact of the parent company.

His idea of the double suicide attacks became a hallmark of the organization, and he wrote a treatise in which he summarized his strategy in “causing as many casualties as possible” to the United States. His hatred of the Americans was increased by the death of his wife, a son and two daughters in the retaliatory bombing of Afghanistan in late 2001. Since then, and despite living in hiding, like Bin Laden, he became in the spokesman for Al Qaeda, with a clear mission: “Fight against the infidels who attack the lands of Islam, with the United States and its lackey Israel at the helm.” The CIA came close to finishing him off in 2003 and 2004 in the tribal areas of Pakistan, before the rise of the even bloodier Islamic State sent Al Qaeda into the limbo of evil. But in one of those twists of fate, the end of Al-Zawahri was not sealed by the US president who most zealously declared “war on terror,” the Republican George W. Bush, but rather by a more timid Democrat who was in dire need of scoring points.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.