Undocumented in their own land: Brazil’s ‘invisible’ citizens

Millions of Brazilians do not have a birth certificate or any other identity papers, which prevents them from going to school, seeing a doctor, finding formal work or receiving a state pension

Adriana is 22 years old, but she hasn’t yet been born. At least not officially. The young Brazilian is dark, slim, with a ballerina’s posture and styled eyebrows, and she lacks a birth certificate. Nor has she got a national identity card (known as RG in Brazil), or a work permit, or any other kind of documentation. “I don’t exist,” she says in a low voice, almost inaudible. Having never known her father, Adriana was raised by Mônica, who her father went to live with when she was five years old. When he abandoned the family, it was her stepmother who discovered she had never been registered, leading to a years-long odyssey to obtain the papers that prove Adriana is a Brazilian citizen. “Her life is on hold; she can’t enroll in courses, she can’t work in a formal job, she can’t do anything,” says Mônica, 46.

Adriana is one of almost three million people in Brazil who have not been inscribed in any way – with a birth certificate, for example - at the Civil Registry, according to estimates by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). In a society riven by social inequality, the absence of official papers to lend people the bare minimum of dignity is not something that frequently appears in the public debate, but the issue gained broader recognition when it cropped up at the National Secondary Education Exam (Enem) in Brazilian high schools, where students were asked to write about the following subject: “Invisibility and the Civil Registry: guaranteeing access to citizenship in Brazil.”

Without being on the Civil Registry, in Brazil it is impossible to enroll at school, receive government social benefits, or even to see a doctor in the public health system. As the exam question suggested, undocumented Brazilians are not considered citizens and have little hope of getting ahead in life.

Adriana managed to study and finish secondary school thanks to the insistence of Mônica, who convinced officials at a public school in the suburbs where they live – “but a cheap one” – to let her enroll. “And I was lucky that she was a healthy kid, she never needed to go to the doctor, which is just as well because if she had, I don’t know what we would have done,” says Mônica.

This year, however, Adriana had to seek the help of a social worker to get her Covid-19 vaccinations. “We went to several distribution centers and they wouldn’t vaccinate her because she doesn’t have any ID,” adds Mônica.

Both women are speaking to EL PAÍS in the courtyard of the Juvenile and Senior Citizens Court of Río de Janeiro, located at Onze de Junho square. They are standing in front of a bus belonging to the Río Court of Justice, where six employees of the Ombudsman’s Office, four social workers and three judges under the remit of the Itinerant Justice program are offering help to dozens of people who are seeking the documentation that will accredit their existence. Adriana and Mônica, who wants to officially adopt her stepdaughter and give her her surname, arrived at 6am on their what is their fourth visit and once again left disappointed. As they have no documentation for Adriana’s biological parents, it is necessary to search paternal records in the Civil Registry to regularize her situation.

“Sometimes it makes you want to give up, but we have to ensure her rights,” says Mônica. “I find all this very confusing; it makes me feel very discouraged,” adds Adriana, her head always bowed, her speech almost monosyllabic. She averts her eyes when speaking. Shy, when she agrees to a photograph, she finds it hard to look at the camera. Shame is a recurring sentiment among undocumented people, says Raquel Chrispino, a judge who has worked with this section of the population for 15 years and coordinates a program at the Court of Justice called Eradication of Under-Registration. “They feel it is their fault they don’t have any documents, as though they are fifth-class human beings,” she says.

Chrispino explains that, without being inscribed on the Civil Registry, children and adults alike find it difficult to access education and healthcare. For example, for these Brazilians it was impossible to take advantage of the emergency aid offered by the government during the pandemic. “Those in need can’t even obtain the medication offered by Social Security; healthcare for them is always a matter of going to the emergency services. In all these years I have lost count of the number of blind people I have attended to. Old people with cataracts that couldn’t be operated on because they aren’t registered,” says the magistrate, who has become almost an activist against under-registration.

Chrispino is one of the primary sources for journalist Fernanda da Escóssia, who has been covering the undocumented since 2003 and is author of the book Invisíveis: uma etnografia sobre brasileiros sem documentos (or, Invisible: an ethnography of undocumented Brazilians), which was one of the supporting texts for the Enem exam. For three years, she visited the Itinerant Justice bus in Onze de Junho square to tell the stories of people who were refused treatment for cancer or whose families have up to three generations of undocumented members. “Many of them told me that they feel like dogs, that they talk about themselves as non-people, because the undocumented are excluded from the world of basic rights,” says Escóssia.

During her investigation – her book is an adaptation of her doctoral thesis – Escóssia found that documentary exclusion in Brazil has a structural basis, which begins with a lack of integration in the systems of bureaucracy, such as notaries, who are responsible for drawing up birth certificates, and the state secretariats of Public Security, which control the registry. Other factors include parental abandonment, which is practically endemic in Brazil, racism and sexism. “I met a woman who has no papers because her father said he wasn’t going to have a ‘very black’ daughter to his name, and another whose father only registered his sons because ‘women don’t need it’,” she says.

In the 20 years she has spent covering the issue, Escóssia has witnessed how the number of under-registered people has dropped in Brazil from 20.3% in 2002 to 2.1% in 2019. According to international studies, this has been achieved in part due to the implementation of income transfer programs, such as the social assistance program known as Bolsa Familia (Family Allowance), which now requires documentation from all beneficiaries. But beyond the problem of those people who have never been recorded by the Civil Registry is the so-called issue of “inaccessible duplicates” – when someone has lost their original documents and faces a steeplechase of bureaucracy and financial outlay to obtain new papers.

Unfortunately, the Brazilian government does not see the issue as a strategic policyRaquel Chrispino, judge and activist

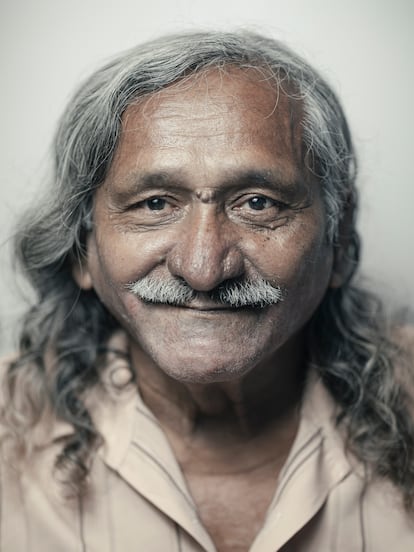

This is what happened to Antônio Gecínio de Lima, 69, who left Natal, the capital of the northern state of Río Grande del Norte for Río de Janeiro at the age of 16 “without a handkerchief and without documentation,” as Caetano Veloso sang in his popular 1967 tune Alegria, alegria, in the midst of the dictatorship. Last week, without knowing whether or not he was registered in the city of his birth, he climbed into the bus in Onze de Junho square in Río for the first time to find out if he could retire. “I never studied and I’ve always worked, but I’ve never had a formal job. I never married, but I have two sons who can’t take my name on the registry because I have no documentation,” he says.

In his bureaucratic search for an identity, Antônio has had the help of a friend, Paola dos Santos: “He is living in a state of total abandonment, alone, and he can’t get any kind of social benefits,” she says. Together they left their meeting with the judge in Río with a request to search the civil registry in the notary’s offices in Natal and the wider metropolitan region. The first step is to find out if at some point Antônio’s birth was registered there between 1950 and 1954.

Luis Gustavo, who thinks he is 37 years old, is in a more complicated situation. He knows he came to Río at the age of three but he is not sure if he was born in São Benedito, the city in northeastern state of Ceará where he believes his family are from. After spending seven months sleeping rough because he couldn’t afford the shelters where he normally stays, he sought the help of the Itinerant Justice service after being approached by a police officer who, upon finding out that he was undocumented, gave him the address of Onze de Junho. “An acquaintance has offered me a job delivering water, but to be able to work I need at least an ID card, right?” he asks a social worker resignedly. City officials in Río de Janeiro estimate there are between 8,000 and 10,000 people living on the city’s streets. “A large percentage of them say that they can’t leave the streets because they don’t have any documentation,” says Chrispino.

Much like Adriana, Luis Gustavo carries the weight of shame of those that feel they are not people in their own right. Wearing jeans, sandals and a Brazil soccer shirt, he looks at the floor while he speaks. “I am not ashamed to live in the street, but I have never got to know anyone here because it is as though I am not a citizen. If I don’t even have a piece of paper with my name on it, I don’t have anything.”

Solutions

Of the 35 or so people who were seen by the social workers and magistrates on the last Friday of November in Río, all identified themselves to officials as “morenos” (dark-skinned) or “Black.” And judging by their clothes and their own stories, all were “poor or very poor,” as Fernanda da Escóssia writes in her book.

Documentary exclusion, when all is said and done, reflects almost every aspect of social inequality in Brazil. Rogério de Oliveira, a 54-year-old Black electrician, and his son Wiliam, 27, caused a scene when they arrived for their meeting with one of the judges. It was their first visit, triggered by Rogério’ discovery that Wiliam had never been registered. “I had a problematic relationship with his mother. We separated, but I was always there. As I gave her my papers and she told me that the boy had a certificate [of birth], I thought everything was in order,” says Rogério. After finding out that his son was “caught up in some trouble,” Rogério wanted him to study and find work, and only then did he discover that Wiliam was undocumented. “I never suspected anything because I always enrolled him in the private schools in our neighborhood, I gave them his name and that was that.”

According to Raquel Chrispino, situations like Wiliam’s and those of millions of undocumented Brazilians can be avoided through the integration of documentation policy. “The state secretariats of Public Security do not communicate with each other in this chain of documentation. The databases and the services offered to citizens need to be integrated to combat ‘counter syndrome’,” she says, in reference to the pilgrimage many people are forced to make to innumerable windows at public service offices to be registered on the Civil Registry, hearing the word “no” countless times until they chance upon the right place. “Nobody believes that these people exist, but there are millions of them. Of the 42,000 people deprived of liberty in Río de Janeiro, 3,000 have no civil identity with the state,” adds Chrispino.

As well as the integration of registry systems (which in Brazil are managed by notaries) and systems of identity (handled by the states through the secretariats of Public Security and other departments like the Department of Traffic), Fernanda da Escóssia says that it is necessary to strengthen the committees to tackle under-registration. “The bureaucratic structure of the state needs to be less insensitive to this issue. Schools and health centers, for example, could and should act as active referral centers for these people when there is an evident lack of documentation,” she says. Experts agree that, as well as making life easier for Brazilians by guaranteeing access to a basic right, perhaps even the most primordial right, these measures would also save the public coffers money. “Unfortunately, the Brazilian government does not see the issue as a strategic policy” notes Chrispino.

While the status quo remains the same, Wiliam’s day has started with good news. After his meeting with the judge at Onze de Junho square, he went straight to a notary across the square where he finally obtained a birth certificate. And that was just the beginning: along with the precious sheet of paper, he had a meticulously handwritten list with the details of seven more documents he is now able to ask for, including a national RG identity card and a work permit. “I’m so happy, what a relief!” he beamed. All the shyness in the world could not mask the euphoric smile of someone feeling like a person for the first time.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.