How does artificial intelligence think? The big surprise is that it ‘intuits’

Something extraordinary has happened, even if we haven’t fully realized it yet: algorithms are now capable of solving intellectual tasks. These models are not replicas of human intelligence. Their intelligence is limited, different, and — curiously — turns out to work in a way that resembles intuition. This is one of the seven lessons we’ve learned so far about them and about ourselves

Artificial intelligence was born in the 1950s when a group of pioneers wondered if they could make their computers “think.” After 70 years, something tremendous has happened: neural networks are solving cognitive tasks. For 300,000 years, these tasks were the exclusive domain of living beings. Not anymore. It’s not controversial: it’s a fact. And it has happened suddenly. Machine learning with neural networks has solved problems that eluded machines for decades:

- ChatGPT, Gemini, or Claude handle language

- They have fluent and encyclopedic knowledge

- They write code at a superhuman level

- They describe images at a human level

- They transcribe at a human level

- They translate at a human level

- Other models generate realistic images, predict hurricanes, win at Go, and drive cars in Phoenix.

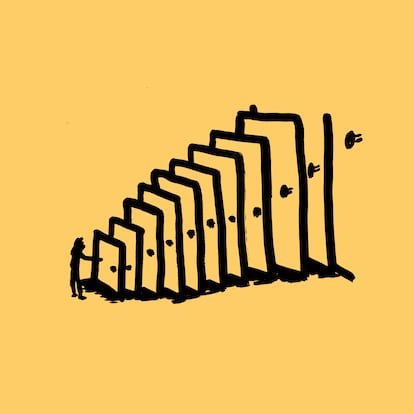

AI researcher François Chollet sums it up this way: “In the last decade, deep learning has achieved nothing less than a technological revolution.” Each of these achievements would have been a remarkable breakthrough on its own. Solving them all with a single technique is like discovering a master key that unlocks every door at once.

Why now? Three pieces converged: algorithms, computing power, and massive amounts of data. We can even put faces to them, because behind each element is a person who took a gamble. Academic Geoffrey Hinton kept working on neural networks long after his colleagues had abandoned them. Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s CEO, kept improving parallel‑processing chips far beyond what video games — the core of his business — actually needed. And researcher Fei‑Fei Li risked her career to build ImageNet, an image collection that seemed absurdly large at the time.

But these three pieces aligned. In 2012, two of Hinton’s students, Ilya Sutskever and Alex Krizhevsky, combined them to achieve spectacular success: they built AlexNet, a neural network capable of “seeing”—recognizing images — far better than anything that had come before.

The rumor spread quickly through the laboratories: this worked. Hinton’s team had found a formula: networks, data, and computing in gigantic quantities.

The impact of this transformation will be profound. As Ethan Mollick, one of the most astute observers of our time, has said, even if AI development were to stop tomorrow, “we would still have a decade of changes across entire industries.”

No one knows how far these machines will go. Between the hype promising superhuman intelligence every year and the denial that ignores the obvious, we are missing something crucial: current AI models are already fascinating. The latest big surprise is that they work in a way that closely resembles intuition. Their development forces us to confront deep questions — about how they work and how we do. And they have already given us some answers..

Lesson 1. Machines can learn

It’s the most overlooked and least controversial lesson: machines learn. James Watt’s centrifugal governor (1788) already adjusted the speed of steam engines without supervision. It was the beginning of a discovery: you don’t need to fully specify the rules of a device for it to work.

Classical programming consists of defining rules and expecting answers: “This is how you add; now add 2 and 2.” But machine learning works the other way around: you give it examples, and the system discovers the rules. Chollet sums it up in Deep Learning with Python: “A machine learning system is trained rather than programmed.” The most powerful example is the large language models like Claude, Gemini, or ChatGPT. They are neural networks — tangles of computational units connected in successive layers, imitating the neurons of the brain — with hundreds of billions of parameters that are adjusted during training. Every success and every mistake tweaks those parameters. This learning process is extremely long, opaque due to its sheer scale, but not mysterious. It’s mathematical. And it has worked.

Hidden here is what the field calls the “bitter lesson.” For decades, experts tried to encode their knowledge into machines. They failed. What succeeded was creating the conditions for knowledge to emerge… and stepping aside.

Lesson 2. AIs have emergent abilities

The bitter lesson hides a profound idea: something complex can emerge from simple processes. It is the principle that organizes life. Evolution didn’t design each organ; it set in motion a process — mutation, recombination, selection — and from there sprang eyes, wings, brains. Now we have replicated that process in machines.

Let’s return to large language models (LLMs). Without going into the divisive topic of defining their capabilities, it’s clear they handle language with flexibility. You can converse with ChatGPT; it detects sarcasm and responds to changing contexts. But no one programmed it with grammar or explained sarcasm to it. How is this possible? Most experts assumed that mastering language fluently would require general intelligence (something human‑like across a wide range of tasks). Yet it turned out that the simple training task of “predict the next word” had emergent power.

The procedure is simple. The first training of an LLM is what we call pretraining: the model is presented with snippets of text from the internet and asked to predict the next token (a word or fragment). When it fails, the parameters responsible for the error are adjusted. This simple process, repeated an astronomical number of times, ends up creating models that predict words very well… and that learn much more along the way.

For Carlos Riquelme, a researcher at Microsoft AI, this was a crucial discovery. He shared his astonishment from 2017, when he was working at Google Brain: “I was amazed by the power of scaling. By scaling a very simple method [predicting the next word] with large amounts of data and powerful models, it became clear that it was possible to largely replicate human linguistic capacity.”

The key is this: to predict words you need to grasp complex concepts. Suppose you have to complete these sentences, which Blaise Agüera y Arcas compiles in a brilliant new book, What is Intelligence?.

- “In stacks of pennies, the height of Mount Kilimanjaro is…”

- “After her dog died, Jen didn’t leave the house for days, so her friends decided…”

Filling these gaps requires geographical knowledge, mathematics, common sense, and even “theory of mind” to put yourself in Jen and her friends’ shoes. In this way, “what seemed like a narrow linguistic task — predicting the next word — turned out to encompass all tasks,” argues Agüera y Arcas in his book. For example, when presented with the phrase about Kilimanjaro, Google’s latest Gemini 3 model thinks for a minute and then responds (correctly): “The height of the mountain is approximately 3.9 million cents.” For Jen’s friends, it offers different options, from “showing up at her door with ice cream” to “taking turns visiting her.”

Agüera y Arcas provides another example in an email exchange: multiplication. An LLM like Gemini or ChatGPT might have memorized common calculations from the internet, such as “2 × 7.” But they also predict “871 × 133,” which doesn’t appear anywhere. “Successfully performing these operations generally implies having inferred non-trivial algorithms from examples.” It’s the trick of emergence: a simple process produces complex capabilities.

Lesson 3. AI learns with a ‘crappy evolution’

Our AI doesn’t learn like people. A child is born with a lot of innate “machinery,” and then learns with little data and few experiences, with remarkable efficiency. The pre-training of an LLM is very different: it begins with a blank slate and learns very slowly with millions of examples. The topic is cats: training an AI to identify cats in an image requires thousands of photos, but a two-year-old can distinguish them by seeing three.

There’s a better analogy: evolution. The renowned researcher Andrej Karpathy describes LLM training as a kind of “crappy evolution.” In a recent podcast, he spoke about how surprising its development has been: “we can build these ghosts, spirit-like entities, by imitating internet documents. This works. It’s a way to bring you up to something that has a lot of built-in knowledge and intelligence in some way, similar to maybe what evolution has done.”

Why does this analogy work? Because evolution also arises from a vast number of tiny trials and changes (mutations and symbiosis), repeated over millions of years. It’s a slow, blind process that ends up embedding capabilities in living beings: instincts, reflexes, or patterns. It’s chaotic and noisy. That’s why each gene influences many characteristics of an organism; and that’s why medicines have side effects, because they disrupt circuits other than the intended one.

Actually, the surprise of an AI mastering language by predicting words — which surprised Riquelme — reminds me of the shock that Darwin caused: how to accept that animals, people, and even his poems are the byproduct of a blind process that only seeks to “maximize copies”?

Lesson 4. We have automated cognition

François Chollet is cautious when speaking about artificial intelligence. He prefers to call it “cognitive automation.” True intelligence, in his view, will require something that current models lack: “cognitive autonomy,” the ability to confront the unknown and adapt. Chollet wants to curb the hype, although at the same time he acknowledges a remarkable achievement: we are automating cognitive tasks on an industrial scale. “What’s surprising about deep learning is how much can be achieved with pure memorization,” he says via email. For him, LLMs lack the deliberate and efficient reasoning that humans possess. That’s why, initially, they made crude errors, such as miscounting the r’s in the word “raspberries.” What surprises him is that they can often compensate for that lack of reasoning: “If you have almost infinite experience, intelligence isn’t so critical.”

Other experts see more than just memorization: are we witnessing real intelligence? Andrej Karpathy believes so. On Dwarkesh Patel’s podcast, he explained that pretraining does two things: “Number one, it’s picking up all this knowledge, as I call it. Number two, it’s actually becoming intelligent. By observing the algorithmic patterns in the internet, it boots up all these little circuits and algorithms inside the neural net to do things like in-context learning.”

Jeremy Berman, creator of the leading algorithm in the ARC Prize, became convinced by the new reasoning‑focused models, which emerged about a year ago and include learning stages without examples: “I was surprised that you can train a model on its own attempts, and that allows it to think and learn for itself,” he explains in a message exchange. He is referring to reinforcement learning (RL), described by the creators of DeepSeek R1. “If you present a math problem to an LLM, let them answer 100 times, and train them on their best answers, the LLM learns. This goes beyond the pure memorization of pre-training.” Thanks to this, the latest generation of models can solve long, complex problems that their versions from just a few months ago were unable to handle.

Carlos Riquelme points out that there are semantic differences: “Algorithms, mechanisms, and ways of reasoning can be memorized. Some might call that ‘circuits for thinking,’ while others might say that the algorithm was simply memorized, like how we learn to add.” Furthermore, Riquelme emphasizes that real-world learning is more active. From the moment the model generates its responses and receives feedback, “it can end up memorizing something that wasn’t in its initial data.”

Agüera y Arcas believes that AI is real intelligence — without further qualifiers. He thinks models like Gemini, ChatGPT, or Claude display a capacity for generalization that goes beyond what we can reasonably call memorization. And he is surprised that Chollet argues otherwise: “What evidence is he looking for?” he asked. For Agüera y Arcas, nature already shows that intelligence comes in many forms, such as Portia spiders — which plan cunning attacks — or octopuses, which distribute their cognition across their arms.

Lesson 5. It’s more intuitive than rational

Here comes the paradox. In the 20th‑century imagination, robots were supposed to be cold, rational machines: logic, calculation, deduction. But today’s AI works the other way around..

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman, Nobel laureate in Economics, distinguished two systems in human thought. System 1 is fast, automatic, and intuitive; it uses shortcuts and patterns. System 2 is slow, deliberate, and rational; it requires conscious effort. The former dominates our lives. A baby knows how to nurse, we pull our hand away from fire, we hold a glass with just the right force… Things that took robots decades to learn.

What’s surprising is that early LLMs operate much closer to System 1 than to System 2. They mimic the style of Jorge Luis Borges, they write with rhythm. They do things without being able to “explain” how — just like us. They don’t reason step by step; they’ve absorbed patterns at massive scale. And deliberate reasoning — deduction, counting, logic — is precisely where they struggle.

That’s why recent innovations seek to add reasoning. The aforementioned “reasoning” models — from DeepSeek R1 to the current generation — write for themselves before responding, generating more cautious and reflective, step-by-step thought processes. Other advances pursue the same goal: reinforcement training that rewards correct reasoning, launching multiple attempts in parallel and selecting the best one, or connecting models to external mathematical tools that overcome their limitations. It’s an attempt to build an artificial System 2. And it’s working, at least to some extent: the newest models excel at math and spatial tests where the first LLMs failed.

Lesson 6. Humans are also patterns

If AI captures patterns and uses them to write, translate, and draw, an uncomfortable question arises: how much of us works the same way? Perhaps more than we like to admit. We already know that our brains rely on constant shortcuts. Watching how machine learning performs, it’s hard not to wonder how much of what we traditionally attribute to talent or experience — writing with rhythm, choosing colors, sensing tone — is actually automatic.

The history of science is the history of dismantling our exceptionalism. Galileo showed we are not the center of the universe; Darwin showed we are not special creations; neuroscience showed we are not one but many. Now AI adds another lesson: abilities we once felt were uniquely ours can be captured through large‑scale pattern recognition.

Lesson 7. We are living through a Cambrian explosion of AI

Today’s AI systems have deep limitations. Andrej Karpathy listed some of them in the podcast mentioned earlier: “They don’t have enough intelligence, they’re not multimodal enough, they can’t do computer use [...] They don’t have continual learning,“ he said. ”They’re cognitively lacking and it’s just not working. It will take about a decade to work through all of those issues."

But a new avenue has opened up with the successful formula of networks, data, and computing. That’s why we are living through a Cambrian period. Like that explosion of life 540 million years ago, when a multitude of animals suddenly appeared, we are now seeing an explosion of novel approaches to artificial intelligence. There are laboratories exploring fascinating directions: Sara Hooker is working on adaptive systems, Fei-Fei Li wants to build models that decipher the physical world, and François Chollet is researching AIs that write and evolve their own logical programs.

How far will these attempts go? Blaise Agüera y Arcas sees no limits: “Our brains achieve incredible feats of reasoning, creativity, and empathy. And those brains are circuitry: they are not something supernatural. And if they are not supernatural, they can be modeled computationally.”

Will we achieve this in practice? Nobody knows. But the question is no longer theoretical. We are watching algorithms learning to read, write, program, and reason — clumsily at times, astonishingly at others. Whatever happens from now on, this has already occurred. And it is extraordinary. Perhaps it will end up being the most important transformation of our lives.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.