The unknown story of the first Olympic hero: An unexpected victory and a sad and premature end

Spyridon Louis, a humble water carrier without any athletics training, was the first great hero of the Olympic Games when, at the last minute and against all odds, he brought victory to Athens in 1896

In one of the few surviving photos of his feat, Spyridon Louis, sporting an impeccable brigadier’s moustache, wears a number 3 on the breastplate of his white round-necked shirt, bloomers, a belt with a thick buckle, high socks, clog-like sneakers and a discreet beret covering his hair. With this dignified attire — not barefoot or covered in rags, as the sensationalist press claimed days later — Louis ran the marathon at the first Olympic Games of the modern era, held in Athens, on April 10, 1896.

About 11 kilometers from the finish line, in the suburb of Kipermi, he paused for a final refreshment stop. Legend has it that he went into a tavern to ask for a glass of red wine, but the truth is, apparently, that it was his girlfriend, Eleni, and his future father-in-law who came to meet him to offer him half an orange and a glass of cognac. At that point, Spyridon — Spyros to his friends — was still in third place, behind the Australian Edwin Flack and another Greek athlete, the heavy pre-race favorite Kharilaos Vasilakos. Eleni told him to hurry up; they were way ahead of him. But Spyridon took a last bite of the fruit segments, scanned the horizon and the narrow road that climbed, among olive trees, through the hills of the Athenian suburbs, and assured her that he would not be long in catching them.

Louis knew those hills like the back of his hand. They were the scene of his daily chores, the corner of the world where he spent his days delivering, at a trot, carafes of mineral water to his father’s customers. Vasilakos began to feel faint on the next climb. Flack, an elite middle-distance runner who had never run such a long distance, dropped out at the 36-kilometer mark, unable to overcome a violent attack of hypoglycemia, which we know today as “the marathon wall.”

With his rivals gone, Louis was left alone in the lead and continued to trot at that steady, unassuming pace, slow only in appearance, which so exasperated his instructor, Colonel Papadiamantopoulos. If this were a story of fiction, we would say that the athlete dedicated that lonely final stretch, that definitive assault to the heavens, to recalling his childhood as an apprentice shepherd in the humble village of Marousi, his (few) days in the Greek army, his daily routines as a water carrier, or his courtship with Eleni.

The truth is that we don’t know what went through his head. 40 years later, in a rare interview given during the Berlin Olympics in 1936, he said he barely remembered the “roar” of the nearly 100,000 people who were waiting for him on their feet inside the newly inaugurated Panathenaic Stadium. They were cheering his name and that of his country, celebrating at last, on the fifth day of the Games, a Greek being proclaimed champion of one of the athletics events.

The birth of a myth

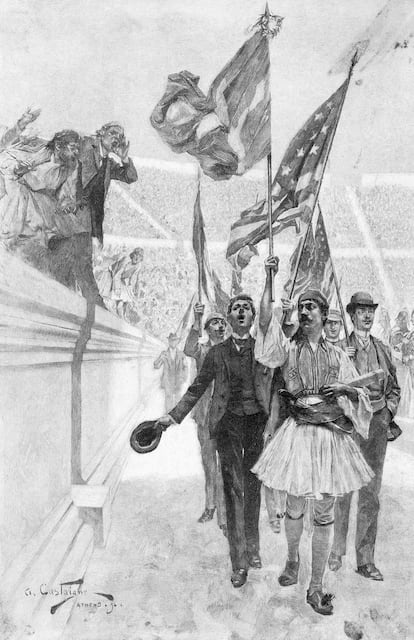

Once in the stadium, there was what Emilio Fernández Peña, director of the Olympic Studies Center of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB), describes as “an instant of magic, almost unrepeatable on a symbolic level. A cyclist had just informed the crowd that the man in the lead was indeed a fellow countryman. Two members of the Greek royal family, Princes Constantine and George, came down onto the track to greet the champion and rode alongside him for the last few meters, in full dress uniforms, hats and monocles, carrying ornamental sabers.

The young Hellenic monarchy, before the fervor of the masses, paid homage to the humblest of its heroes, a 23-year-old water carrier from Attica, illiterate and without many options in life. In Fernandez Peña’s view, “the potential of sport to generate contemporary mythologies, to exacerbate patriotic pride and thus reinforce a national brand or, above all, to serve as a social elevator for people of very humble origins” was intuited for the first time.

After being subjected to this incipient display of sporting populism, Louis was left alone in the center of the track. The closing ceremony and trophy presentation was scheduled for April 15, five days later, but the athlete was carried on his shoulders to the dressing room, where King George I was waiting to offer to make any of his wishes come true.

Overwhelmed by the circumstances, the new popular idol did not ask for a mansion in the hills or a noble title, merely a wagon and a mule with which to deliver his carafes more comfortably. The writer Javier Muro describes the scene, tinged with magical realism, in his story Spyridon Louis and the legend of the water carrier. The athlete accepted, at once, a restorative massage without being entirely clear about what such words implied. As soon as the masseur touched his legs, Louis jumped, stood up and announced that he had to leave. His girlfriend and her friends were waiting for him to celebrate his success on the other side of the hill. And off he went. Running back the way he had come.

The million-dollar cup

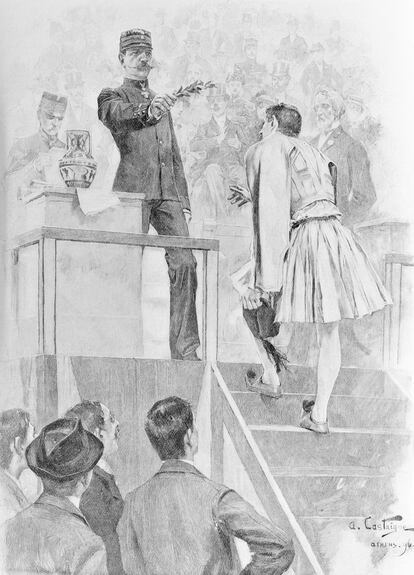

Five days later, Louis would return to the scene of his triumph to receive his Olympic medal and an unexpected gift: a silver cup from French academic Michel Bréal, the man who had devised the modern marathon and convinced his good friend, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, to include it in his Olympic program.

The athlete’s family would keep the cup on a shelf in their home in Marousi for decades, next to a framed photo of “grandfather” Spyridon. They never thought it could hold any value beyond the strictly sentimental. In 1989 a sports historian, Karl Lennartz, traveled to Marousi, was greeted by the Louis family and held in his hand the by-then-legendary Bréal Cup, that Holy Grail of the Olympic spirit.

It was Lennartz who informed Manuel, Spyridon’s 10-year-old great-grandson, that the object was probably worth “many millions of drachmas,” a phrase that the boy did not take entirely seriously. According to the German researcher himself, the president of the International Olympic Committee at the time, Juan Antonio Samaranch, asked Lennartz to try to acquire the cup on behalf of his institution, although without specifying how much money they were willing to pay for it. The family preferred to keep the trophy, but they later put it up for auction at Christie’s, in April 2012, where it fetched almost $900,000.

The courier and the colonel

This legend of the prehistory of sport also has a beginning and a denouement to match its exciting plot. The opening chapter helps us understand the extent to which Spyridon Louis, born in a hut on the outskirts of Marousi in 1873, was an accidental hero.

As sports performance expert Roger Robinson explains, Louis had never participated in any formal competition previously: “He had no coach, no training program, no specialist diet and had never set foot in a gym.” Louis was a “virgin” athlete. His only asset was the more than 30 kilometers he ran daily, often at a jog, carrying and selling the mineral water carafes that his father filled at the springs of Marousi through the streets of Athens and its periphery.

Two years before the 1896 Olympics, Bréal had proposed at a conference at the Sorbonne that a “ritual race” be organized in homage to Pheidippides, the Greek courier who, according to Plutarch, ran the 42 kilometers from Marathon to Athens in 490 B.C. to announce that the Greek army had defeated the Persian invaders. One of the attendees pointed out to Bréal that Pheidippides, in Plutarch’s account, died of exhaustion shortly after reaching his destination, a probable indicator that a 42-kilometer race was not something within the reach of human beings. Bréal, despite everything, managed to get his tribute to the stories of ancient Greece included in the Olympic program. As it transpired, it became the star event.

In the year leading up to the first Games of the modern era, it became clear that it was unlikely the Greek team would achieve any notable success. Although it ended up being a largely local competition, with 230 national athletes compared to only 83 from 13 other countries, the foreign legion was the clear favorite in the vast majority of events.

There was little that the enthusiastic Greek youth could do against athletes trained at the most prestigious institutions in the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Hungary or Australia at a time when competitive sport was the preserve of an elite of wealthy university students. As such, the government of George I decided to allocate resources to a not entirely well-calibrated Olympic training program. And that’s where Colonel Papadiamantopoulos came in.

An unconditional fan of athletic competitions, the military man on leave of absence tried to put together a team of Greek long-distance runners capable of winning a medal. It soon became clear to him that, in events such as the 800m or 1,500m, it was going to be almost impossible to compete against semi-professional athletes as experienced as the aforementioned Edwin Flack or the Frenchman Albin Lermusiaux. So the colonel focused his efforts on the marathon, an unprecedented event and, consequently, fertile ground for surprises.

The water carrier who took them all on

Papadiamantopoulos assembled a team of recruits led by the promising Vasilakos and began to work with them, determined to show them that 42 kilometers was a distance that could be covered at a good pace without faltering, in about three hours. Shortly before the race, the colonel decided to invite a military cadet who had already graduated, Spyridon Louis, because his fellow recruits assured him that, despite his peculiar way of running, he was the best long-distance runner of them all and knew the Attica hills surrounding the stadium better than anyone.

Louis dutifully kept his appointment with his former commanding officer but finished fifth in a training marathon held 17 days before the Games. Papadiamantopoulos felt that the boy had not tried hard enough but was impressed that he arrived much fresher in appearance than his teammates. He included him in the team, although he did not consider him his best asset.

On April 10, when 13 Greek runners and four foreigners stood on the starting line of the first marathon in history, the locals had already suffered defeats in sprint and long-distance races and even in events inspired by those of classical Greece such as the triple jump or the discus throw. Another foreign victory would have been received as a full-fledged humiliation. But Louis, with the orange and the shot of cognac still vivid on his palate, came to the rescue.

Prison and the olive branch

Then came the denouement. Louis never took part in a sporting event again. He was expected to participate in the Olympic marathon at the Paris Games in 1900 and even in St. Louis in 1904, but he did not compete at either of them. By then, the sport had already provided him with everything he could wish for: his medal, his silver cup, his carriage, his mule and (the best prize of all), permission to marry his bride.

Although the popular press persisted in presenting him as a national hero and inventing bizarre stories about his past (it was said that he was a goat herder, the bastard son of a member of the high aristocracy of Attica, lover of divas and princesses), he preferred to keep a low profile, refusing even such peculiar offers as that of becoming an ambassador of a famous Athenian barbershop in exchange for free shaves and haircuts for the rest of his life. He was not a broken toy, because he never took the repercussions of his sporting achievement entirely seriously. He carried on with his life, without nostalgia or false expectations.

In 1926, he was imprisoned for falsifying military documents to collect a pension he was not entitled to. Not even a popular petition for a pardon spared him from spending nearly a year in prison before he was acquitted. In 1936, the organizing committee of the Berlin Olympic Games traveled to Marousi to ask him to participate in a then-pioneering initiative: the route of the Olympic torch from the temple of Olympia to the German capital.

They wanted Louis, as the first great Olympic hero, to take charge of the first relay. But they found him a premature old man at 63 years of age, barely able to walk let alone run a long distance with a torch in his hand. Still, he went to Berlin by train, on what was the longest journey of his life. It is said that his neighbors took up a collection to buy him a fustanella, an ancestral Balkan skirt, so that he would look presentable for his first public appearance in almost four decades. Adolf Hitler received him with full honors in a ceremony in which Louis presented the dictator with an olive branch, the ancestral symbol of peace. The old hero gave a couple of interviews and returned home to the comfortable shadows in which he had spent most of his life.

Four years later, in March 1940, a few weeks before Italian troops invaded his homeland, the water seller died of a heart attack in Marousi. The two hours, 58 minutes and 50 seconds it took him to take to the skies one spring afternoon in 1896 will be remembered.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.