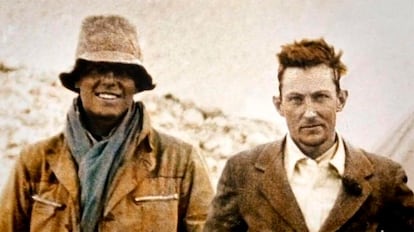

Everest’s enduring mystery: Were Mallory and Irvine first to conquer world’s highest peak?

Almost a century after his disappearance, the remains of Andrew Irvine and the camera that could prove that he and George Mallory summited in 1924 have still not been found

Somewhere on the North Face of Everest is — or should be — an old Vest Pocket Kodak, whose film could rewrite the history of the mountain. The most coveted camera in the history of mountaineering disappeared in 1924, and until 1999 it was believed that it would be found along with the remains of George Mallory. But that wasn’t the case. Logic dictates that it should then be among those of Andrew Irvine, Mallory’s climbing partner, whose whereabouts remain unknown. A century later, at the foot of Everest, corpses of aspiring climbers continue to pile up, but the trivialization of the horrific makes the list of the missing a minor statistic.

This spring, 17 of the 500 mountaineers who have climbed or attempted to climb the world’s highest peak have perished. Collateral damage for those who manage the business of Everest, where apparently only one dead climber remains important: Irvine, who disappeared in 1924 and, with him, the camera that could reveal the greatest mystery in the history of mountaineering: did Irvine and Mallory reach the summit, becoming the first people in history to do so?

Discovery of Mallory’s body

In 1999, the case may have been solved, but the search confounded scholars of the English climbers’ fate. Conrad Anker, a member of the Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition, had barely been searching for his needle in the haystack at 8,200 meters for 90 minutes when he bent down to adjust a boot and noticed something strange beside it. It was slightly to the right of the normal route of the North, or Tibetan, face of Everest, where the first attempts to conquer the roof of the planet took place between 1921 and 1924, with Mallory participating in all of them. Anker and his team assumed that, taking the account of Noel Odell, the last person to see Irvine and Mallory alive at 8,600 meters, for granted and believing that the pair would never have been able to climb the second step on the approach to the summit with the means available in that era, both must have fallen more or less on the vertical section of the obstacle.

The winds that sweep over the upper reaches of the mountain leave a field of exposed rocks, a scree that uncovers everything buried by snow during the monsoon. And there, next to Anker’s boot, was a mummified body lying face down, with its back in the air, one bare foot crossed over the other, on which was a very old hobnailed leather boot. Remnants of a linen rope were preserved, tied around the waist of the deceased, who was wearing clothing dating from the era of the early Everest expeditions. Straw-blond hair still visible on the corpse’s head convinced Anker that he had found Irvine, who was nicknamed Sandy because the color of his hair. Mallory, on the other hand, had brown hair.

However, when Anker and his companions examined the remains, they discovered from the label on the shirt collar that it was in fact Mallory, whose hair, exposed to the elements for 75 years, had turned a whiteish hue. Upon lifting the mummified corpse, they were surprised to find that they had no trouble identifying Mallory’s features and they searched the six layers of clothing he had been wearing. There they found a small treasure trove: a box of matches, three letters, a handkerchief, a pocket knife, a broken altimeter, a sewing kit.... but there was no trace of the camera, whose original owner was Howard Somervell, another of the climbers on the 1924 British expedition: he had lent it to Mallory. Neither did they find the photograph of Mallory’s wife, Ruth, which he had intended to leave at the summit. The fact that his sunglasses were also in one of his pockets could indicate that he had taken them off when descending from the summit in the dark; or equally that he had removed them during the day for better visibility when he and Irvine became caught in a storm.

Kodak technicians assured Anker’s team that the film, which had been frozen for decades, might be recoverable if the camera itself was undamaged. And if they succeeded in developing the images, perhaps one of them would be the photograph that could end the mystery as to whether Mallory and Irvine reached the summit. The search had been organized based on the account of a Chinese climber, Wang Hongbao, who claimed in 1975 to have seen a corpse at an altitude of 8,100 meters, which he believed to be an “Englishman.” At that time, no one was known to have perished on Everest at that altitude: it had to be either Mallory or Irvine. The discovery made the front pages of the world’s media.

The search for Irvine

The expedition mountaineers covered Mallory’s remains with rocks, as a burial, but this gesture did not mean an end to the search for new clues. The most serious attempts in this regard came in 2019, when Mark Synnot, like Anker a member of The North Face athlete team, decided to search for Irvine’s remains based on new information. Synnot recounts in his book The Third Pole how previous expeditions had been unable to locate Mallory’s remains despite having the exact position of their location: where the GPS said they should be, there were only stones. Had someone removed them? Synnot and his team worked on the mountain as the physical extension of Tom Holzel, a veteran Everest researcher and author of The Mystery of Mallory and Irvine, who thought he knew for certain where to find Irvine’s body.

At home, he had studied a high-definition image of the area and had marked an odd spot, a reddish color that clashed with the rest of the landscape. In addition, Holzel based his theory on the accounts of Sherpa Chhiring Dorje, who claimed in 1995 to have encountered a very old corpse dressed in military fatigues at an altitude of 8,400 meters. The second key piece of testimony came from the Chinese climber Xu Jing, who reported in 1960 seeing the same thing at a similar altitude after leaving the route in search of a shortcut to his final altitude camp.

But most astonishing of all, as Synnot’s book reveals, is that in 1965, Wang Fuzhou, one of the three Chinese climbers who reached the summit for the first time from the north ridge in 1960 (albeit without providing concrete evidence), claimed during a press conference in Russia to have come across, at 8,600 meters, the corpse of “a European wearing braces,” such as those worn by Irvine. Wang did not disclose whether the remains were above or below the second step. Holzel plotted all the possible routes Xu Jing could have followed to his high altitude camp. He ruled out those that ran along rock walls and settled on one possibility that he studied under a microscope, on which he discovered the reddish spot. That’s where Synnott headed.

Since 1938, no one had set foot on Everest from the Tibetan side. After World War II, China closed its borders, while Nepal opened them, welcoming all attempts that led to the first recognized ascent in 1953 by Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary. Today, much more credibility is given to the claimed first ascent of Everest from Tibet, and China considers that 1960 feat as theirs, denying any possibility that Mallory and Irvine had achieved the summit 36 years earlier.

Beijing’s official discourse has also erased the testimonies of Xu Jing and Wang Fuzhou. Such zeal could also hide a supposition, based on rumors issued by officials of the Chinese Mountaineering Association, referring to a far-fetched but plausible possibility as Synnott himself has acknowledged: that shortly before 2008, a Chinese expedition removed Irvine’s remains from the mountain and with them the secrets he may have been carrying, and perhaps even the contents of his camera.

Noel Odell died at the age of 96, but he always maintained the real possibility that Mallory and Irvine had reached the summit. He never altered his discourse, despite pressure from his compatriots on the Everest Committee: it was easier to organize new attempts if it was taken for granted that the summit had not been reached. On June 8, 1924, Noel Odell witnessed what he thought might be Mallory and Irvine on the summit, described it thus and left an exciting mystery that remains unsolved a century later: “At 12.50, just after I had emerged from a state of jubilation at finding the first definite fossils on Everest, there was a sudden clearing of the atmosphere, and the entire summit ridge and final peak of Everest were unveiled. My eyes became fixed on one tiny black spot silhouetted on a small snow-crest beneath a rock-step in the ridge; the black spot moved. Another black spot became apparent and moved up the snow to join the other on the crest. The first then approached the great rock-step and shortly emerged at the top; the second did likewise. Then the whole fascinating vision vanished, enveloped in cloud once more.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.