Jeremy Lin: ‘They called me coronavirus’

Jeremy Lin seemed to have it all to succeed in the NBA. A new documentary tells the story of the mixture of prejudice and bad luck that cut his career short

“The ways of the Lord are inscrutable,” Jeremy Lin told a reporter in February 2012, right after a game against the Utah Jazz. He had scored 28 points, a career high up to that point. He was 23 years old then and in the process of becoming the leader of a struggling New York Knicks team. He was still two games away from facing the Lakers and Kobe Bryant, who had publicly disparaged him in a press conference: “Jeremy Lin? I don’t know who that is.” Ten years later, lots of people know who he is because of everything that has happened since then, and now because of a new documentary about him, 38 at the Garden, which is available on HBO Max.

Lin, now 34 and of Taiwanese descent, didn’t take kindly to Bryant’s words and prepared the response he would deliver if he had a good game. Never in his wildest dreams could he have imagined what would transpire on February 10, 2012, at Madison Square Garden: Lin dominated the game against the Lakers and led his team to victory. He scored 38 points, four more than Bryant’s 34. The phrase he had prepared, according to sources close to the player, was: “I guess Kobe knows who I am now.” But when the game ended, Lin didn’t dare say it. He politely answered the reporters’ questions and left to celebrate the victory with his teammates.

Jeremy Lin grew up in a devout Christian home. As a student at Harvard University, he used to meet with his friend Adrian Tam to read the Bible, and he always stuck to his habit of praying before games. He started playing basketball at the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) in California. At 6′3″, Lin played point guard and led his high school team to the state championship. He was a diligent student and got good grades in almost every subject. He also served as the editor of his school newspaper and was a summer intern for Democratic California State Senator Joe Simitian.

After finishing high school, he compiled a DVD of his best plays and mailed them to the colleges in which he was interested. None of his preferred destinations offered him a scholarship (despite being named the best player in Northern California’s division), so he went to Harvard, which is better known for its academics than its sports. Nonetheless, Lin shone on the court and broke Ivy League records. In 2010, he graduated with a degree in economics. But none of these accomplishments proved enough for him to be selected by a professional team in the NBA Draft.

Lin then embarked on a career shaped by both bad luck and racial prejudice. The Dallas Mavericks offered the undrafted Lin a spot on the team’s Summer League roster. There, he surprised a few scouts with several brilliant performances. “It was amazing to see an undrafted rookie play like that,” said the then-coach of the Golden State Warriors - the team that ultimately offered Lin a roster spot - in his post-signing press conference in 2010. Lin chose to wear the number seven because of that number’s importance in the Bible, and he became the first Asian-American player in NBA history.

The Golden State Warriors didn’t make it easy for Lin. The point guard position was already occupied by two of the league’s stars, Stephen Curry and Monta Ellis, and Lin barely got any playing time. He spent the entire summer in the gym trying to bulk up. But before he had a chance to show the team his progress, Lin was traded to the Houston Rockets; they were not interested in his services, either. Lin ended up with the New York Knicks as the fifteenth man on the roster.

There was little reason to believe that Lin’s fortunes would change in New York. Udonis Haslem, then a Miami Heat player, says that before playing a game against the Knicks, he met Lin inside the Madison Square Garden chapel. He recalls that the pastor asked the players if they wanted to pray for anything, and Lin requested that the priest pray that he not be kicked off another team.

‘Linsanity’

The shy Asian-American basketball player’s situation was quite precarious for someone in the NBA. He was the lowest paid player on the roster, and his contract wasn’t even guaranteed. He slept on the couch at his brother’s house for fear of being released and not having the money to pay the rent in New York.

But Lin’s unlucky streak came to an end. The Knicks were in a slump, and several key players were injured. Knicks head coach Mike D’Antoni’s assistants convinced him to try Lin because he had “something special,” the coach said in a recent interview. Lin’s opportunity came on February 4, 2012, in a game against the New Jersey Nets. He came off the bench and ended up being the team’s leading scorer with 25 points. The Knicks won, and the first chapter of “Linsanity” was opened.

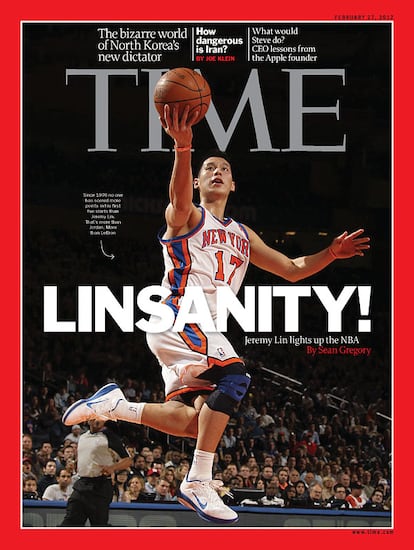

The Knicks reeled off seven consecutive victories in which Lin averaged over 25 points and 8 assists per game. He impressed with stellar performances, such as his 38-point game against Bryant and the Lakers and a game-winning buzzer-beater against the Raptors. The public and the media went wild over him. He appeared on the cover of Time magazine with ‘LINSANITY!’ emblazoned in huge letters over his photo, and he graced the cover of Sports Illustrated twice in a row (Michael Jordan is the only NBA player to have done so three times). Lin’s popularity was such that NBA commissioner David Stern intervened at the last minute to include him in the rookie All Star game, which was held in Orlando that year.

Jeremy Lin is a good player but all the hype is because he's Asian. Black players do what he does every night and don't get the same praise.

— Floyd Mayweather (@FloydMayweather) February 13, 2012

Linsanity soon went international. China and Taiwan bought the Knicks’ broadcasting rights and fought to claim him as a valuable national asset. The Knicks increased their merchandising sales by 300%. For two months, Lin’s number 17 jersey was the best-selling jersey in the NBA. But his impact was not merely economic. The Palo Alto-born player’s story of self-realization became a source of inspiration for thousands of young people of Asian descent who dreamed of becoming athletes in a country that still retained the stereotype of the polite, rule-abiding, unathletic Chinese. Personalities such as Barack Obama and Paul Auster celebrated him. After a lifetime of dedication and sacrifice, the fates had finally conspired in Lin’s favor. But his most difficult trials still awaited him.

Some never really bought into the Linsanity phenomenon. Boxer Floyd Mayweather tweeted that Lin’s performances were being exaggerated: “Jeremy Lin is a good player, but all this hype has been generated because he is Asian. There are a lot of black players who do the same thing he does every night and don’t get the same attention.”

Six weeks before the regular season ended, Lin suffered a small meniscus tear in his left knee. He was forced to watch from the bench as his team was eliminated in the first round of the playoffs. That summer, his contract expired. The New York Times had dubbed him “the Knicks’ most popular player in the last decade,” so it was logical to assume that his contract would be renewed quickly. But the franchise let Lin go, fueled by envy in the locker room and, possibly, prejudice towards a player who perhaps had not managed to break as many stereotypes as it seemed. Lin didn’t hide his disappointment: “Honestly, I’d rather have stayed.”

The long fall

Lin ended up at the Houston Rockets, who had made him a good offer. Everything seemed set until the arrival of James Harden, one of the league’s biggest stars, who also happened to play the same position as Lin. During the season, Lin’s performances were far from the level he had shown the previous year and he played his best basketball when Harden was resting on the bench. The expectations around him were deflating; Lin began to rack up injuries, and he lost confidence in his game. From then on, he switched teams virtually every year. He never recaptured the magic of his 2011-12 season. In 2019, he won his first and only NBA Championship with the Toronto Raptors, although he played a secondary role on the team.

The following year, he didn’t attract interest from any NBA franchises. He had to pack his bags and head to China, where he signed to play for the Beijing Ducks for $3 million per year. Lin recaptured his form and was one of the best players in the Chinese league. His level rekindled his hopes of returning to the NBA, but team offices back in the United States told him that he would never attract the attention of an NBA team while he was playing in China. Once again, Lin packed his bags. In his eleventh year as a professional basketball player, he agreed to play for the Santa Cruz Warriors, a G-League team designed for young players to develop their game and secure an NBA contract; his salary was $30,000. Even then, at 32, Lin proved that he could still perform at the highest level. He was the G-League’s seventh-leading scorer and ranked fourth in assists. Still, NBA executives were unmoved.

Lin described his time with the Santa Cruz Warriors as “the most realistic moment” of his career. That stint in the G-League put him on par with “99% of minorities and people who have to struggle uphill.” The situation has only gotten worse since then. In 2020, his final year as a professional, when he was desperately trying to return to the NBA, an opponent called him “coronavirus” in the middle of a game. A climate of hostility toward Asians had spread across the United States, largely because of the Donald Trump-sanctioned campaign to blame the Chinese for causing the Covid-19 pandemic. Shortly thereafter, Lin told journalist Anderson Cooper: “You can hear it in the audio recordings: there’s cheering and laughter when they call me ‘Kung-Flu Virus.’”

As Lin recently explained to The New York Times, incidents like that encouraged him to participate in the making of 38 at the Garden, the documentary that chronicles Lin’s brief epic - the story of an Asian-American basketball player who would not turn out to be an NBA star but did beat one of the greatest hoopers of all time in a personal duel. But despite it all, Lin himself said that his career had been “a miracle from God.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.