The women who broke the silence about the terrifying organization that trapped and abused them during Spain’s dictatorship

The Board for the Protection of Women was created during Franciso Franco’s regime, with the objective of ‘redeeming immoral women.’ Through podcasts, books and roundtables, abuses and violations of human rights that took place within this repressive system are finally being documented

Inmaculada Valderrama was 15 years old when she died. Supposedly, she fell from a window on the third floor of the female reformatory in San Fernando de Henares, a suburb of Madrid. According to the official version of events, she was trying to escape from the facility. However, Immaculada was in her underwear and the doors of the center – at that moment – were already open. That same day, a demonstration was organized in the municipality, blaming those in charge of the reform school – all of them Evangelizing Catholics – for the young woman’s death. It was September 19, 1983.

Although General Francisco Franco had died eight years earlier, the longest-running and most misogynistic institution of his dictatorship had survived him: the Board for the Protection of Women. This organism – as fearsome as it was unknown – formed part of the mechanism of a system of social control, which focused on disciplining the bodies and minds of women. It was designed and applied by the Catholic Church and the hierarchs of the regime. To do so, they relied on historical models, such as the Royal Board of Trustees for the Repression of White Slavery (1902).

Paradoxically, the Board for the Protection of Women was created during the Second Spanish Republic (1931-1939) with a completely different purpose. The name was appropriated following the Nationalist rise to power. Franco’s regime subverted it, essentially turning it into a “patriarchal prison network.” Within this system, members of the Catholic Church were given police functions.

“If you behave badly, they’ll take you to the nuns.” This was the threat that was made to thousands of women on a daily basis throughout the 36-year-long fascist dictatorship. A large majority of them didn’t know what exactly the threat was referring to: the much-feared nuns, convents, or residences. The Board for the Protection of Women was created in 1941 with the objective of “redeeming fallen women and helping those who were in danger of falling.” Fallen women… fallen from what? What abyss were they descending into? Was it a fall from heaven to hell? Surely, no one would have been able to answer which place was the one from which, apparently, only women fell. But what anyone would have been clear about – both then and now – is that this concept referred, indisputably, to women engaging in prostitution… or simply women who took control of their sexuality. This second type of “fall” was extremely broad. It ranged from those who smoked to those who went to protests. It included women and girls who were disobedient, or, worst of all, those who became pregnant out of wedlock. Any female in this situation was perceived by the government and religious authorities as deserving lifelong social punishment. Under Franco, they would be forced to give up their child for adoption. Many infants were often sold.

Carmen Guillén – a Spanish historian – wrote a thesis about the Board for the Protection of Women. She describes how this system of social control was essential to ensuring the stability of the dictatorship, since “the woman was in charge of transmitting values to her offspring and, consequently, their indoctrination. [Controlling women] was a priority.”

The death of Inmaculada Valderrama in 1983 marked a before and after in the survival of the Board for the Protection of Women. Just two years later, it was extinguished, like any other leftover Francoist institution… albeit without any reparations for the victims.

The majority of religious orders that carried out the confinement of thousands of women – none of whom were convicted of any crime – continue to be involved in the field of social services. Even Spain’s Democratic Memory Law – which came into effect in 2022 – doesn’t consider the female inmates as victims of the dictatorship. However, a few women born after this system disappeared are bringing its cruel history to the surface, while recovering the memories of its survivors. Since last year, in fact, we’ve witnessed an outbreak of women breaking their silence, via books, articles, roundtables and podcasts on the subject.

Lunatics

“On November 9, 1977, in Basauri prison, María Isabel died of shock due to burns. The prostitutes who worked in that area – her colleagues – didn’t believe the official version of events and called for something like a strike… the feminist movement demanded that the crimes that only applied to women and the [feminist] movement be repealed. LGBTQ [movements] requested the abolition of the Law of Danger and Social Rehabilitation, [which criminalized homosexuality].”

“43 years after her death, from my house – [less than 1,000 feet] from the last residence where she was registered – I try to reconstruct the life of a [lady] who always fought not to be killed. Someone once told me that people like that leave no trace. Now, I know that they were absolutely wrong.”

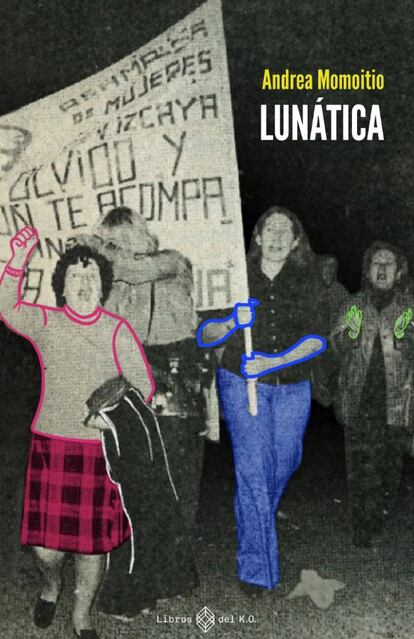

In 2022, Andrea Momoitio, 35, published the story of María Isabel Gutiérrez Velasco under the title Lunática (“Lunatic”). Momoitio is a journalist who researched the story of this woman, who lived on the margins of society, pushed there by the mechanisms of patriarchal repression that flourished during the dictatorship. Others have also engaged in this research.

Érica Santillán – after reading Lunatica two years ago – wrote this message on Twitter: “Thank you for bringing me closer to an unknown world but, above all, thank you for bringing me closer to my grandmother.” Neither of them could imagine that this would be the beginning of a friendship that would lead them to join Isabel Cadenas Cañón to turn the search for Loli – Erica’s grandmother – into a podcast under the title Lunatics.

Momoitio’s book jogged Erica’s memory: thanks to the story, she recalled an unfinished conversation from decades ago, in which her mother told her that her grandmother didn’t have a national ID card, because she was wanted by the state.

Isabel Cadenas Cañón, 42, has spent years reflecting on the different material elements that the expression of memory acquires. Her doctoral thesis was titled Poetics of Absence: Subversive Forms of Memory in Contemporary Visual Culture. Her interest has led her to create one of the best-rated podcasts in Spain: We Don’t Talk About That. In it, she weaves together episodes about recent – and not-so-recent – history. She has dedicated two episodes to two survivors of the Board for the Protection of Women, showing how the institution managed to survive for 10 years after the return to democracy. In the episode Lost, she has structured it as if it were an old cassette tape: “side A” is the story of Consuelo García del Cid (in black and white), which takes place during the Franco regime, while “side B” is that of “Dolores” (in color), following the return to democracy.

Consuelo García del Cid: the pioneer

“I’ll make sure everyone knows what they’ve done to us in here.” This was the promise that Consuelo made to her classmates at her reformatory – Adoratrices de Madrid, located at 52 Padre Damián Street – as she said goodbye after two years of being locked up, without having committed any crime. She broke the silence on the reformatories a little less than 20 years ago. As the voice of Isabel Cadenas tells us, it was initially difficult for Consuelo to research this institution, because she came across – in her own words – “a [lack of documents] and an information gap.” But that didn’t stop her. She needed to fulfill the promise she had made in her adolescence. So, she started looking for her former prison companions, interviewing them and asking for documentation. Then, she recounted her experiences and the fruits of her research on televisions. Thanks to her appearances, new testimonies began to emerge.

Consuelo dedicated herself to putting everything in writing: The Banished Daughters of Eve, The Insurgents of the Board for the Protection of Women and Pray For Us are some of the works that have served as an obligatory reference for Spanish researchers delving into this topic. In her own words, “democracy forgot about us and that was an atrocity committed against minors, who – in addition to other punishments and labor – were even made to undergo virginity tests. And it’s no use telling me ‘that’s just how Spain was.’ That prison system for minors was an unquestionable atrocity.”

Unworthy

“Chelo Alfonso was one of the many young pregnant women who passed through the Santo Celo [reformatory]. She was 14-years-old when she became pregnant and, when she told her aunt, the reaction was [terrible]. Two men put her in a car and she was taken to Oblate Reform School, in Valencia. When she went into labor, she entered the La Cigüeña clinic under a false name… the general anesthesia prevented Chelo from remembering the slightest detail of giving birth. She woke up crying and asking about her son. She never got to see the newborn. Without time to recover from [the trauma], they locked her in the Adoratrices de València Reform School.”

This is just one of the many horror stories that Marta García Carbonell and María Palau Galdón collect in their book. These two journalists heard about the Board for the Protection of Women for the first time when they were working on a report about the women’s prison at the Convent of Santa Clara in Valencia. And, from the moment they learned of its existence, they devoted their lives to discovering and describing the modus operandi of this prison and patriarchal framework. Just one year after that discovery, they obtained a major Spanish research scholarship for journalism, thanks to which they have seen the fruits of their labor published: Unworthy Daughters of Their Country. In their book – filled with maps and photographs – they also point out the spaces and religious orders that were part of this punitive network.

The leading thesis in this field of study – The Patronage for the Protection of Women: Prostitution, Morality and State Intervention during the Franco Regime – was published by 36-year-old historian Carmen Guillén, who analyzes the parallelism between the Catholic-Nationalist alliance in Spain and the model of social control implemented by Italian fascism. “[Asylum-like] centers were used not only for women with psychiatric problems, but also for those who didn’t fit the stipulated feminine model.”

The generation of granddaughters

Many of these researchers have met for roundtables, some of them promoted by the Spanish Institute of Women. In these events, a survivor is always included in the audience. One of these women is Pilar Dasí, who initially didn’t speak about the Board for the Protection of Women after she was released from confinement several decades ago.

In these spaces, doubts are raised about how they’re transmitting this experience. Many of the women who passed through these religious centers weren’t aware that they were being held by a specific institution. Fewer had even heard of the Board at the time. Therefore, they fear that many other women don’t recognize themselves as victims of the same organization.

Be that as it may, we’re witnessing the reparative will of a generation of granddaughters – some of them biological, others metaphorical – who, being aware of the androcentric bias that prevails in historical narratives, have decided to count the women who came before them. They’re sure that, by doing this, they’re counting themselves in the process.

In Autoscience Fiction for the End of the Species, author Begoña Méndez writes: “Where are the biographies of my grandmothers? What traces of my future do their existences contain? My grandmothers left me a blank piece of paper.” These are the questions that are pushing us to finally break the inherited silences.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.