A return ticket for the grandchildren of Spanish exiles in Latin America

A new law in Spain opens a path to citizenship for descendants of people who fled the Civil War and dictatorship. Thousands are now eligible to apply. These are three of their stories, from Argentina, Mexico and Venezuela

Migrating can be a round trip journey, even when it takes generations to return home. In October, Spain’s Congress approved a new law – the Democratic Memory Law – that expands eligibility for citizenship to the descendants of Spanish exiles in Latin America. Dubbed the ley de nietos, or “grandchildren law,” the new legislation streamlines the process for obtaining a Spanish passport for the children and grandchildren of those who fled the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) or the dictatorship of Francisco Franco (1939-1975). The law also opens a path to citizenship for other individuals “whose father, mother, grandfather or grandmother was originally from Spain,” and who meet certain other requirements. But beyond broadening the eligibility and streamlining the process for application, the text of the bill – an expansion of the 2007 Historical Memory Law, which, among other things, grants Spanish citizenship to underage minors with Spanish grandparents – has major symbolic implications as well.

Those interested in applying for the program must submit documentation proving their ancestry by October 21, 2024. Spanish consulates across Latin America have already received thousands of applications. What follows are the stories of three of these applicants – one from Argentina, one from Mexico, and one from Venezuela.

Argentina

“My grandparents worked digging dirt and rocks.”

Juan Manuel de Hoz’s maternal grandparents were born in Catalonia and emigrated to Argentina in 1930, escaping conditions of poverty and hunger. His paternal grandparents, who were from Cantabria, on Spain’s northern coast, migrated to Argentina as well, but then returned to Spain at the beginning of the 20th century. After three years back in Europe, they realized that their prospects were better in the Americas, and returned. In those days, Argentina was a land of opportunity, and between 1880 and 1930, the country welcomed more than four million immigrants.

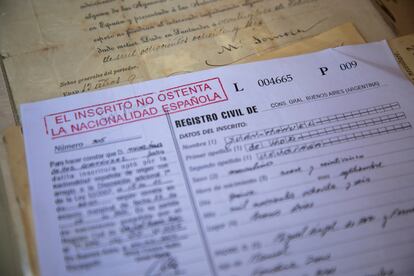

Like his parents, De Hoz was born in Argentina. In 2008, when he was 22 years old, he applied for Spanish citizenship at the consulate in Buenos Aires. His application was denied. At the time, only descendants of Spaniards under the age of 21 were eligible to apply. His younger brother met the requirement, but De Hoz and his older brother did not. He never stopped trying, but the red stamp of rejection remained on his paperwork for 14 years. This October, however, De Hoz’s luck finally changed with the passage of the Democratic Memory Law. Three weeks after the bill went into effect, De Hoz was a citizen of Spain, and one of the first Argentines to take advantage of the new law.

“The [Democratic Memory] Law closes family wounds,” De Hoz says, sitting in a café in Buenos Aires and holding in his hands the paperwork that certifies his newly acquired nationality. “I wanted it out of a desire for belonging, for my family ties. My maternal grandparents were Catalan, and on my father’s side they came from Cantabria.” For the beneficiaries of the law whose grandparents fled Spain to escape political and ideological persecution, or persecution based on their sexual identity, Spanish citizenship represents a symbolic form of reparations – if not for the victims of the Civil War and the dictatorship themselves, then for their descendants.

For De Hoz, who is 36, what began as a personal cause gradually became a collective struggle. “We started forming groups on Facebook, then we set up a web page and started holding informational sessions,” says De Hoz, who now serves as the spokesperson for the Centro de Descendientes de Españoles Unidos (Cedeu), or the Center for United Spanish Descendants.

Of the 2.6 million Spaniards living abroad, almost a fifth live in Argentina: 473,519, according to data published by Spain’s National Statistics Institute (INE) in January 2020. The Spanish community in Argentina is almost double that of France, and triple that of the United States —– the other countries where the diaspora is most concentrated. Cedeu says that with the passage of the new legislation, they expect roughly 120,000 more Argentines to apply for Spanish nationality. The consulate in Buenos Aires, which was overwhelmed by applications even prior to the passage of the new law, plans to increase staffing to accommodate the growth in demand.

Among the memories of his grandparents that De Hoz cherishes the most are the stories of their humble origins. “They would tell me about how they worked digging in the dirt and rocks. They were very poor,” he says. Like many immigrants, De Hoz’s grandparents eventually began to make progress in their new country. His maternal grandparents opened a barber shop, and later a store that sold vinegar – businesses that neither their children nor grandchildren carried on. His paternal grandparents settled in the province of Mendoza, in the heart of Argentina’s wine country, to try their luck at agriculture. De Hoz regrets that his parents were not still alive to see him become a Spanish citizen. “It’s also in honor of them, especially my father, who passed away in October, just before the law was passed.”

Mexico

“Spain is part of my roots, and it would feel terrible to lose that”

During the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath, more than 25,000 Spaniards migrated to Mexico, earning the country its fame as a refuge for sympathizers of the Spanish Republic. And many of these exiles married each other and made families in their new country. This is why Jaime Celorio Manjarrez, 50, can count numerous grandparents, uncles, aunts, and in-laws of Spanish origin. His father was born in Mexico and had Spanish nationality when he was a minor, but lost it when he turned 18. With the passage of the Democratic Memory Law, he has regained his lost nationality. Jaime’s wife also has Spanish citizenship, as do his children, who acquired it thanks to her. But not Jaime, who has been stuck in administrative limbo, waiting for a miracle. Now, with the new reform opening eligibility to the grandchildren of Spanish exiles, he hopes to finally join his family in obtaining a Spanish passport.

Celorio has already filed his paperwork for citizenship, along with documents proving that his heritage can be traced back to Spain’s northern region of Asturias and to the Canary Islands, a Spanish archipelago off the western coast of Africa. “We have our traditions, because we grew up listening to our grandparents. My uncle wrote a lot about that,” he says, alluding to his uncle Gonzalo Celorio, a Mexican academic, writer, critic and editor, and one of the many Spanish immigrants who made successful lives for themselves in the town that welcomed his parents – the Mexican refuge where their bones, if not their souls, were eventually laid to rest, after surviving a bloody war and an ideological purge.

Mexico offered Celorio’s grandparents the opportunities that they had been denied in their homeland. For Jaime Celorio, who has traveled to 30 different countries, Spain is a world apart from the rest. “The language, the food, the people, the culture. You come to Spain and everything feels natural. It feels like home,” he says. “Even my surname is immediately recognized there.” Celorio’s father also travels from time to time, but their family is as Mexican as mole. Jaime was a financial director for Goldman Sachs and Merrill Lynch, and now works as an entrepreneur and is in charge of several firms, the most important of which is a tequila export company. “Spain is part of my roots and if I can get [my nationality] back, well, that’s great. It would feel terrible to lose that part of who I am.”

Venezuela

From the Spanish Line to Spanish citizenship

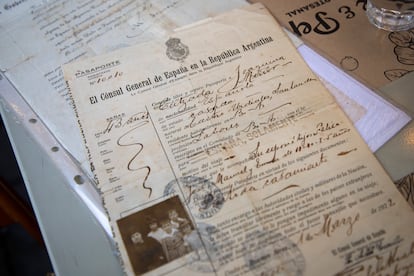

On October 14, 1964, Ismael Rodríguez Pérez boarded the Spanish Transatlantic Company’s passenger liner, Monserrat, bound for the Port of La Guaira, Venezuela. His travel documents indicate his destination as both “La Guaira” and “La Guayra” – the Venezuelan and old Castillian spellings of the port city’s name, respectively. He travelled in economy class, carrying his smallpox vaccination certificate. Fifty-eight years have passed since Ismael’s transatlantic journey to South America, and 17 since his death. His original ticket is now part of a stack of documents that includes the birth certificates of three of his grandchildren, who are now around the same age as their grandfather was when he emigrated. Thanks to the Democratic Memory Law, these documents now form the basis for his grandchildren’s’ applications for citizenship, which will be processed by the Consulate of Spain in Caracas.

Ismael was 25 years old when, like many Spaniards, he left a country ravaged by the miseries of war and dictatorship. He arrived to the shores of South America one year after his siblings and parents left their family home in the Canary Islands to start a life somewhere else. In Venezuela, they survived by farming and managing a bakery. But Eredia Rodríguez, the daughter of Ismael, whose mother was Venezuelan, never managed to obtain Spanish citizenship due to complications with her registration paperwork. Her application was filed by an aunt and not by her parents, which created a bureaucratic mess that proved impossible to clean up.

Thankfully for Eredia, who now needs those substantiating documents for the application process she has undertaken for her children, the aunt who filed the application held on to those original documents. The only knowledge Eredia has of her father’s escape from Spain are from the stories he told her. “He always said that the trip had been good, that everyone on the ship was happy and jovial,” she says. “And, since he liked to dance, that he had danced. My dad said – as everyone says – that when he arrived in Venezuela it was like he had found a gold mine, and that they were welcomed with open arms. That’s why they never focused on having things in Spain, because here they had everything.”

Thanks to the “grandchildren law,” Eredia’s children will acquire citizenship before she does, even though she is the daughter of a Spaniard. In fact, because of the complications with her previous application, Eredia, who is 51 and works in business, is confident that now, with the passage of the new law, she actually has a better chance at streamlining her citizenship application by basing her claim on her relationship to her grandparents, who migrated to Venezuela shortly before her father did. “First, I’m going to do the boys’ application. That’s more important, even though they don’t have any plans to leave. But it’s their right, and that’s why we are going to file the paperwork,” she says.

The Spanish Consulate in Caracas has received almost 500 citizenship requests since the law was approved in October. They expect to process tens of thousands of applications during the next two years that the law is in effect, and potentially more if the deadline is extended. The consulate began approving applications in November, and has now granted citizenship to roughly 60 people. As in other countries, the consulate in Caracas has increased the number of available appointments, to meet the increase in demand.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.