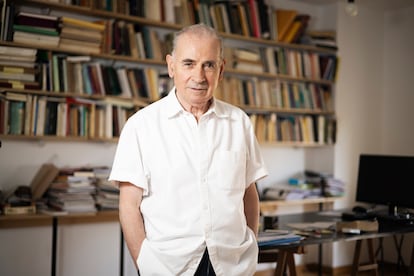

Víctor Gómez Pin, philosopher: ‘I don’t think an algorithm can conceptually reflect on Kant’s categorical imperative’

The Barcelona thinker analyzes what he terms as the defeat of the left and artificial intelligences, which, he doubts, will be able to ‘produce something that science doesn’t already know’

When Víctor Gómez Pin can’t sleep, instead of counting sheep, he solves mathematical problems. Considered one of the most prominent philosophers of recent years, thanks to a prolific output of over a dozen essays, he has recently been concerned about artificial intelligence, and he has written a book about it, yet to be published.

A French scholar who at 17 went to Paris and trained at the Sorbonne University, Gómez Pin taught for years in his hometown, at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, and won several essay prizes. At the end of September he participated in the Formentor Literary Conversations, held this year in the Pyrenean resort of Canfranc and titled “Cyborgs, androids and humanoids: Science, patience and deficiency.” During a lull in the activities, he gave an interview in which he demonstrated that he is an enthusiast for ideas. At 79, whenever he finds the right way to express himself, he springs up from his chair.

Question. In The Honor of the Philosophers you argue that we should not forget our ability to question and allude to our “passive surrender to everyday life.” Do we think less and less today?

Answer. There has never been a good time for thinking, nor for poetry or art, it is often said. The fight for the dignity of the human spirit involves overcoming inertia, the slope that makes us passive victims of time.

Q. Do we need more poetry?

A. Before bad education, which is to say most education, we were all poets.

Q. You compare education to an “instrument of domination,” more oriented toward forming pieces of a production machine than critical citizens. Is that one of the evils of our time?

A. Well, I don’t know if it’s just our time, but I’m afraid that it happens. But what I believe doesn’t matter. Beliefs don’t interest me at all. Plato distinguished founded opinion from opinion. On Twitter, everyone says what they believe.

Q. But how do you see the issue of education?

A. There was a time when the left, to which I belong, not only generationally, but spiritually, offered a promise of realization of the human spirit freed from alienation. As Aristotle said: all humans aspire by their nature to know.

Q. And what has happened to the left?

A. It has been defeated. When I arrived in Paris, when I was 17, that project allowed you to link the social struggle, due to the feeling of indignation at people’s living conditions, to a project of absoluteness of the human condition. Marx says it in the manuscripts of ‘44: man has to face the total problem of existence.

Q. Do you still believe in communism?

A. The project has gone to hell. But it was wonderful. Social struggle was seen as what would allow us to achieve the conditions of possibility of being human. I regret that it went to waste, but even the capitalist regrets it, because everyone is nostalgic for their humanity. Capital has triumphed.

Q. And that is inexorable?

A. I don’t know. Having been defeated, the left sticks to what is left. Humanity has degraded.

Q. And how do you see this degradation?

A. It no longer occurs to anyone that it is not normal for a person to work 12 hours (they usually work 12 and get paid eight). The life of a Barcelona taxi driver consists of working 12 hours, sleeping eight and in the remaining hours, going to soccer. This has become normalized, and it is intolerable.

Q. In your latest book, The Spain We Loved So Much, you talk about the political conflict in Catalonia. How do you assess the current situation?

A. I face it with a certain skeptical optimism. I quite agree with the policy of the Spanish government regarding Catalonia. It seems to me the most sensible that any government has had since the Republic. And I also believe that, on an empirical level, it is bearing positive results.

Q. In another of your books, Reduction and Combat of the Human Animal, you pointed out that there have never been so many millions of poor people and, meanwhile, pets are taken to the spa.

A. Before, animals were used for energy and they gave you energy back. The farmer fed the dog that was guarding his livestock. Now energy is invested in the dog and affection is demanded. When the dog had its place, affection was demanded of the son.

Q. Is there no room for both of us?

A. Yes, there always was. In any case, I consider myself an environmentalist. I want animals in their space, never sacrificing their nature. A dog, especially if it is large, reduced to an urban space, is outside of its place in nature. Peter Singer himself said it. Abuse can mean having a dog in a space of 40 meters. It does not seem to me that we have progressed in civilization when the affection that we could expect from people we expect from dogs.

Q. A topic that comes up a lot these days is the nightmare of robots that are going to replace and subjugate us. What do you think about that process?

A. There are people very concerned about whether intelligence is going to replace lawyers, scriptwriters... That worries me as a citizen. But I don’t think an algorithm can conceptually reflect on Kant’s categorical imperative the way we reflect. It may know all the science we know, but I doubt it can produce something that science doesn’t already know.

Q. Of everything we are witnessing in the world, what is the phenomenon that worries you the most?

A. Nihilism. There is no political party or country that puts the demand for human dignity first.

Q. Does no political party fight for human dignity?

A. None. Another thing is rhetoric. The motivation of the October Revolution was the cause of human dignity.

Q. For you, the failure of the October Revolution is the failure of humanity.

A. Yes, that is the failure of humanity, not the fall of the Berlin Wall. By then it had long since failed.

Q. And do you think it is possible that there will be a new revolution?

A. I don’t know. But I wouldn’t want to die deceiving myself about it. The October Revolution failed, and a project to dignify the human condition failed. As they say in French, il ne faut pas mourir aveugle [you must not die blindly].

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.