A new map of the endometrium opens the door to possible treatments for endometriosis

The research involves advanced molecular biology and artificial intelligence techniques, and is set to deepen understanding of a disease that affects 190 million women and has no cure

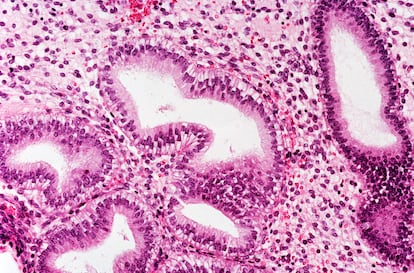

An international team of scientists has published the most detailed cellular map yet of the endometrium — the layer of inner tissue that lines the uterus — thanks to advanced molecular biology and machine learning techniques. This achievement — published in the journal Nature Genetics — could provide some clues for research into endometriosis, a disease about which very little is known, even though it affects more than 190 million women worldwide.

Roser Vento-Tormo, 37, works at the Wellcome Sanger Institute in the United Kingdom, and co-authored the research. She explains that there are several reasons why the study of the endometrium has been historically neglected. According to Vento-Tormo, the main reason is that “generally, little money is invested in everything that has to do with women’s health.”

Another reason is that the endometrium is one of the most dynamic and complex systems of the human body, meaning it is very challenging to study. “It is a tissue that changes its composition every five days and regenerates itself completely every month in a perfect way and without scars,” Vento-Tormo explains.

During the menstrual cycle, the endometrium thickens and prepares the uterus for a possible pregnancy. If this does not occur, the new tissue is shed and comes out through menstruation. This process depends on millions of cells that change their identity and function depending on the type of hormone they interact with at each moment of the cycle, which affects not only their own characteristics but also those of other cells. This creates a chain reaction that is difficult for scientists to track.

The new map works like a compass. “It was like creating a Google Maps of the endometrium that lets us know where each cell is, what it is made of and what type of interaction it has with the cells that surround it,” explains Vento-Torno. To achieve this, the scientists used single-cell sequencing, a technique that allows the genetic material of RNA to be analyzed cell by cell. “It is like having a passport for each unit in which you can read its composition, what function it performs within the body and what it can do on a large scale when it interacts with other cells,” explains the scientist.

This tool is particularly useful for studying the endometrium because it allows researchers to observe how the cells change their identity over time and how they affect the development of abnormalities such as endometriosis. In this disease, the cells of the endometrium leave the uterus and form tissue outside of it — for example on the ovaries or fallopian tubes — which in most cases causes cysts and chronic inflammation that manifests itself in disabling abdominal pain and other complications, including infertility.

In the study, scientists analyzed more than 313,000 endometrial cells collected from 63 individuals of reproductive age. The samples were obtained from participants in previous studies, with 16 new donors joining the investigation. Of the total participants, 30 had endometriosis and 14 were using hormonal medications, either for birth control or to treat the disease. Hormones, along with anti-inflammatory drugs, are the two most common ways to combat the symptoms of the disease. Endometriosis, yet, has no cure.

A common vocabulary

The map will help scientists better understand the female reproductive system and thus develop personalized treatments that respect the needs of each patient. “What we produced was a common vocabulary to integrate all the endometrium data that exists and that will be produced in the future,” says Vento-Torno. “This study is nice because we connected what was disconnected.”

Estela Lorenzo, a specialist in the Endometriosis Unit at the Hospital 12 de Octubre in Madrid, believes that this type of primary research study is a fundamental building block in the construction of scientific knowledge. “The medical revolution in women’s health has to come through this type of exploration,” she says. The map goes a step further than previous publications, adds the expert, because “it talks not only about the type of cells that make up the endometrium, but also about how they develop within one of the most peculiar and curious tissues of the human body.”

Francisco Carmona, a gynecologist specializing in endometriosis, has spent decades investigating the disease and is optimistic about the publication of the new map. “For those of us who work in the clinic, this research is a bit far away, but in the future it will be a tool from which a lot of new knowledge can be generated,” he says. For doctors, the endometrium is a puzzle of ten thousand pieces. “Now, at least, medicine has a common model for everyone to try to put this puzzle together.”

The next step will be to expand the sample of patients in order to broaden the map and better understand each of its neighborhoods and avenues. What scientists are looking for is to detect how the different types of cells influence the correct functioning of the endometrium, which is composed of structural cells and microenvironmental cells — immune system cells that respond to the chemical signals of hormones. One finding is that these microenvironmental cells in patients with endometriosis seem to be more important than the structural cells. Vento-Torno explains: “Most of the changes in sick people occur in these secondary cells that, in theory, are there to provide support. By not providing support, they do not give the correct signals to the structural cells and end up affecting their function.”

The endometrium map is part of the Human Cell Atlas, an international initiative that aims to map the cells of the entire human body. If successful, scientists will have a fundamental basis for diagnosing, monitoring and treating a huge variety of diseases that have uncertain and complex treatments.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.