The first human organ created inside an animal opens the door to manufacturing ‘spare parts’ for people

In an experiment that raises bioethical issues, researchers in China have generated a blueprint of a humanized kidney in a pig embryo

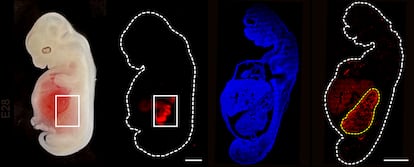

It is a historic image. A team of researchers in China has successfully generated a blueprint of a human organ in another animal for the first time. The experiment, conducted with humanized kidneys in pig embryos, represents a step toward the still-distant dream of using other mammals as an inexhaustible source of organs for transplants. These hybrid organisms — called chimeras, after the mythological monster with the head of a lion, the belly of a goat and the tail of a dragon — still pose major ethical dilemmas.

Researchers at the Guangzhou Institute of Biomedicine and Health have reprogrammed adult human cells to recover their capacity to form any bodily organ or tissue. The team has inserted these pluripotent human cells into pig embryos, which are genetically modified beforehand so that they do not develop porcine kidneys. The human cells have filled that empty niche and generated a rudimentary kidney, an intermediate stage of the renal system called mesonephros. These pig-human embryos were gestated in sows for up to 28 days, about a quarter of the species’ normal period of pregnancy. Half of the cells in their kidneys are human.

Led by Chinese scientist Liangxue Lai, this work continues down the road initiated by Spanish researcher Juan Carlos Izpisua’s team. In 2017, Izpisua announced the creation of pig-human embryos that had barely one human cell for every 100,000 porcine cells. Those pioneering experiments were conducted at the University of Murcia (Spain) and on two Murcian farms. The trials came after intense debate by a committee of experts at the Carlos III Health Institute; ultimately, the committee authorized the trials despite “the biological risks inherent in the generation of pig-human chimeras,” but with the condition that no animal with human cells could reproduce.

Izpisua applauds the new work, in which he did not participate. “It goes a step further and shows that cells can be organized in space and give rise to organized tissue structures,” says the researcher, who is the director of the San Diego Science Institute at Altos Laboratories, a new U.S. multinational that seeks to extend healthy human life. “It has not yet been possible to develop mature humanized organs in pigs, but this study brings us one step closer,” Izpisua observes. “It’s a major step forward.” Worldwide, some 150,000 organs are transplanted every year, but in the United States alone there is a waiting list of 100,000 people and 17 of them die every day, according to official data.

Liangxue Lai and Spanish researcher Miguel Angel Esteban’s team is now working toward the goal of obtaining mature kidneys, attempting to overcome technical and ethical hurdles. One of the red lines is preventing human cells from escaping the kidney and integrating into the pig’s brain or its gonads (testicles or ovaries). “The question is whether it is ethical to let pigs be born with mature humanized kidneys. It will all depend on the degree of contribution [of human cells] in other tissues of the pig,” Esteban opines. His study, published Thursday in the journal Cell Stem Cell, shows that “very few” human cells were dispersed throughout the brain and spinal cord of the pig embryos. “To eliminate any kind of ethical problem, we are further modifying the human cells so that they cannot go to the pig’s central nervous system in any way,” says the Spanish physician.

In 2020, a team from the University of Minnesota successfully generated human endothelium — the inner layer of blood vessels — in pig embryos. A year later, the same group, led by Mary Garry and Daniel Garry, created 27-day-old pig embryos with humanized muscles. Nephrologist Rafael Matesanz, the founder and former director of the National Transplant Organization in Spain, notes that this is the first time a human organ has been created inside another animal. “Conceptually, it is a very important and significant step, but it is not a prelude to producing kidneys, far from it,” the nephrologist says.

Matesanz was one of the members of the committee that authorized Izpisua’s experiments in Murcia. In his opinion, it is “doubtful” that a trial like the one now being conducted in Guangzhou would be approved in [Europe], because of the possibility that some human cells might colonize the pig embryo’s brain, which has actually occurred. “The major risk is for the cells to go to the central nervous system and produce a human-pig. Or for them to go to the reproductive system, [which poses the same risk],” he warns. “[These experiments are geared] toward China, which has much laxer legislation than [Europe] and the United States,” says Matesanz.

The founder of the successful National Transplant Organization believes that “a far more promising avenue” is producing genetically modified pigs so that porcine organs do not cause rejection in humans. On September 25, 2021, a team of surgeons at New York University successfully transplanted a pig kidney into a brain-dead woman. On January 7, 2022, following an operation at the University of Maryland Medical Center, American David Bennett became the first person with a beating pig heart in his chest. Bennett died two months later from heart failure, but there were no apparent signs of organ rejection, although the heart was infected with a porcine virus.

Spanish chemist Marc Güell is one of the founders of eGenesis, one of the U.S. companies modifying pig DNA to generate pig organs for human transplants. Güell also applauds these new results. “It may help to better understand where the current limits of interspecies chimerism are. What else will be required [in the future]?” says the chemist, who is affiliated with the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain.

Nephrologist Josep Maria Campistol, the general director of the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, also emphasizes all the possibilities opened up by pig-human embryos. “They could be an inexhaustible source of organs, [and offer] the possibility of generating specific, personalized human organs for certain patients,” he says. It would be a way to provide a replacement that has a person’s specific cells. Campistol also has faith in regenerative medicine. “I am convinced that, in the near future, we will be able to regenerate chronically diseased kidneys, livers and hearts, to fully or partially restore their function and avoid transplantation,” says Campistol.

Campistol was one of the co-authors of Izpisua’s 2017 research, which demonstrated that human cells could be placed in a pig embryo. “Another very important element, which we are working on, is that these pig models allow you to test different therapeutic strategies to prove their usefulness before moving on to a human patient,” the nephrologist explains. “Obviously, there is still a long way to go, but it opens up some really incredible prospects.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.