DNA reveals the oldest known family tree, dating back to 6,700 years ago

A genetic study of nearly 100 corpses in a French cemetery reconstructs seven generations of a Neolithic clan in which the men stayed in their places of origin for their entire lives while the women went to other groups

Between 2004 and 2007, a group of archaeologists in France excavated a 6,700-year-old cemetery where over 100 corpses of all ages were found. The tombs were individual and had been carefully excavated so that none of them was on top of another. There were hardly any valuables next to the dead, something rare, since the Neolithic revolution that brought sedentary life, agriculture and inequality to Europe was well under way at that time. For the first time in history, it was possible to accumulate large quantities of food, as well as the first riches. For unknown reasons, increasingly large groups began to gather to build spectacular megalithic monuments and tombs where elites were buried along with valuable and sacred objects, such as weapons and animals. In contrast, the French necropolis seemed to be the cemetery of the ordinary people of the day.

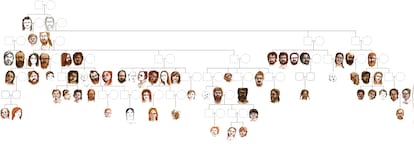

Now, a group of Franco-German scientists has successfully extracted DNA from 94 corpses from the French cemetery to obtain their complete genome. The genetic sequences have traced the kinship links among the deceased to create a family tree that goes back seven generations, making it the largest and oldest one of our species that we know of. The results were published on Wednesday in Nature, the world’s leading science journal.

In this cemetery in Gurgy Les Noisats, south of Paris, researchers found two large family clans, headed by two men. The larger clan consists of 64 relatives, spanning seven generations, all of whom are buried in the same place. The second clan is made up of 12 relatives across five generations. Researchers discovered only one case of crossbreeding between the two groups: one of the mothers from the smaller clan was related to a male from the larger clan. The DNA from this group of people who lived almost seven millennia ago opens a unique window for understanding family, society and culture during an era that is as important as it is unknown (writing did not exist at the time).

The work shows a very clear phenomenon: the men of the family stayed in their places of birth for life, while the women left the family to live with other groups. The strontium isotopes accumulated in their teeth indicate where the water a person drank in childhood came from, and those from the women buried in Gurgy came from many different places. In contrast, hardly any women who were part of the two original clans are at the site. These findings reinforce a trend observed at other later Neolithic sites: the men stayed, while the women left to live and raise families in other groups, a common practice in humans and other primates known as patrilocality, which serves to avoid the problems associated with inbreeding.

Paleogeneticist Maïte Rivollat, the study’s lead author, highlights another surprising finding: “We have found couples that had many children. In one case, we see up to six siblings who lived to adulthood, and in turn had several children, which means a very large family. They probably also had sisters whose remains are not here, because they went to live in other groups.” Her team believes that this indicates great fertility among women and implies that there was an abundance of food and probably social stability. In fact, none of the more than 100 corpses in the cemetery bears a single sign of violence.

Hardly any half-siblings have been found in either of the family’s two clans. No instances of widows and widowers mating with their siblings-in-law were observed. That implies that the couples were monogamous and that there was already a clear idea that having children with close relatives should be avoided.

The Gurgy cemetery raises several unanswered questions. The first person buried here was a woman. The disarranged bones of an older man are next to her; he is the patriarch of the first clan, the larger and older of the two. His remains were buried elsewhere, brought here, and then reburied next to that woman, about whom nothing is known, since researchers have not been able to extract her DNA.

Researchers estimate that Gurgy’s total population was about 1,800 inhabitants, although they have not found any trace of their houses or any other buildings. That reinforces the idea that they were more or less ordinary people. “We don’t know if they were related to the other groups associated with the nearby megalithic constructions, but we think they were,” explains Rivollat.

There was an abundance of food and probably social stability; none of the more than 100 corpses in the cemetery shows any sign of violence

The Gurgy cemetery was used for four generations, just over a century. Then the entire community left, never to return, and no one knows why.

Vanessa Villalba-Mouco, a molecular biologist and expert in ancient DNA, stresses the work’s importance, as it connects the last phase of the Stone Age, the Neolithic, with later times in which metals and weapons made from them had already been discovered. “The work corroborates that patrilocality and female exogamy are not exclusive to the Bronze Age [the first metal age, which began about 3,300 years ago].”

“However, despite the fact that the prehistoric studies to date show patrilocality and female exogamy as a general rule, they all present particularities in their social organization. For example, this new study highlights the absence of half-siblings and polygamy and serial monogamy between sexual partners, an aspect that has been seen in other studies with later samples, including the one we did on kinship relationships in Bronze Age El Argar culture in the Iberian peninsula. We don’t know if what was taboo for some societies was an everyday practice for others,” the researcher explains.

Roberto Risch, a scholar of prehistoric times at the Autonomous University of Barcelona in Spain, thinks that it is “spectacular” that there are cases of up to six siblings who survived into adulthood and in turn had many more children. “We never would have imagined it; and that implies excellent health conditions,” he emphasizes. “It’s also surprising how rigid the exogamy [women being the ones to leave the family home] was. There was a very clear idea of who you were going to have offspring with, and that implies that these societies were very settled and avoided incest. The fact that women moved between groups is very interesting. That implies that they were the ones who acted as a link between groups and probably as a communication channel also,” he explains.

According to Risch, the need to communicate, meet and even have fun drove later societies to get together and create increasingly large monuments, such as Stonehenge in the United Kingdom or the 400-hectare megasite, Valencina de la Concepción, in Seville, Spain. “Thousands of people probably gathered there to communicate, discuss and celebrate, since alcoholic beverages and drugs were already known, as evidenced by the discovery of hallucinogenic substances in a tuft of hair from Es Càrritx, in Menorca, Spain, from 3,000 years ago,” says the prehistory scholar.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.