MSX creator Kazuhiko Nishi: ‘ChatGPT is still very dumb, but it’s only a matter of time’

The Japanese businessman sat down with EL PAÍS to discuss his pioneering years with Microsoft, the future of AI and his take on happiness

Microsoft founder Bill Gates once said: “Of all the people I’ve ever met, Kay [Kazuhiko] is probably the most like me.” Kazuhiko Nishi, born in Kobe, Japan, in 1956, is one of the pioneers of the era that led to the birth of personal computers. He was once the head of Microsoft in Japan and is the inventor of the MSX standard – one of the first and most beloved computers of the 1980s.

At 66, Nishi-San has no intention of abdicating his commitment to innovation. He’s active in many projects, from building more affordable supercomputers, to founding a university in Japan.

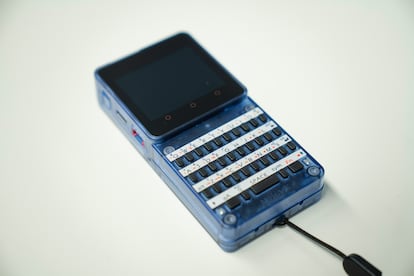

The Open University of Catalonia recently invited Nishi to Barcelona, as part of the celebrations surrounding the 25th anniversary of the Computer Science, Multimedia and Telecommunications Studies program. There, he presented the updated model of the MSX microcomputer, more than 30 years after it became available to the general public.

Today, Nishi is a star, an inspiration for all people who are passionate about programming and computer engineering. A successful businessman who finds his true calling in playing with lines of code, he has the prophetic aura of someone who understood, before anyone else, that technology should get as close as possible to people.

Question. Why did you stop developing MSX 30 years ago?

Answer. In 1983, IBM was promoting their computer, but it was still very expensive and I felt the need to create a cheaper home solution. That’s how MSX was born. However, I was at Microsoft and a company can’t support two competing products. Therefore, the IBM machine became popular because it was more powerful – then investments increased and prices fell. In 1993, MSX was no longer profitable, so I stopped developing it.

Q. Why didn’t your product become the international standard you aspired to?

A. The United States was the Commodore computer’s market. Great Britain was [ZX] Spectrum’s. I was very lucky in Spain, Holland, Italy and Latin America. I was in charge of the design and designers generally don’t care about marketing. Now I’m responsible for everything for the [next model] of MSX and that’s why I’m here, in Spain. Then I’ll go to Brazil, Italy and Holland.

Q. Does the success of retrogaming and the new market for nostalgia have anything to do with your return?

A. No, there are new things here. In 1980, the personal computer was born. In 2000, the smartphone. Every 20 years, a new type of computer is born. Since 2020, it’s the moment of the IoT (Internet of Things). My idea is to produce a very compact MSX [that’s] connectable to IoT sensors: this is the new MSX0, at a price of around $150. Next year, I’ll release the MSX3, which will be connected to the television. And then, the MSX Turbo, which will be a supercomputer. I want to offer a simpler solution than our competitors. I use the BASIC [programming] language, which is old, but still valid and easy to use. Also, I don’t like video games.

Q. But you once said that “you have to learn to play seriously.”

A. I was referring to the problem-solving mentality: there’s a problem and you have to solve it. A climber was asked why he wanted to challenge Everest and he replied: because Everest is right here in front of me. In my life, I’ve encountered many difficult situations and I’ve overcome them all. Even today, at 66, when I run into a problem, I ask myself, what can I do? How will I solve it? Because I know I can work it out and it’s fun to do it.

Q. After so many years, your passion doesn’t seem to let up. What’s your secret?

A. Everyone is born with a God-given mission… but no one knows what it is. Of course, it would be easier to be born with a piece of paper that tells you what the mission will be! Instead, though, we’re all on a journey to find it. I don’t know if it’s my mission, but maybe my talent is engineering. At Microsoft, I did two great things: MS-DOS (Microsoft Disk Operating System) – with GW-BASIC and BASIC extension – and defining the Windows keyboard and mouse, as well as linking the CD-ROM. This is all my doing.

After Microsoft, I made a lot of money with my company working on CPUs (central processing units) and also founded the worldwide community for the MPEG video compression format. When I turned 60, I asked myself what I would do next. I understood that my next challenge would be the IoT.

Q. Did you ever regret leaving Microsoft in 1985?

A. In life, there are positive or negative changes – but they are always your decision. I was very close to Bill Gates: I controlled Japan for the company and only reported to him. But there were other bureaucrats who wanted to take my place. Often, when companies get big, they fill up with ambitious bureaucrats. I decided not to fight and left. Had I stayed at Microsoft, I would now have at least a tenth of what Bill Gates owns. I suffered for about 10 years after that decision. But then I recovered and took my company public. I made about $300 millions: isn’t that enough? For a while, I thought it wasn’t enough, but it was. I mean, I have four helicopters, a Rolls-Royce, a Bentley. So, I’m happy.

Q. Is this your idea of happiness?

A. Everyone is in search of happiness. And then people feel that money can buy happiness. There are two ways of being happy that I have discovered: realizing your dream, being famous, doing a good job, becoming famous. Tons of money. But if you’re only going after money and power and fame, it’s limitless. With assets, you have to be mentally aware, you have to have gratitude. The monks in Tibet are happier than people living with lots. Maybe the coexistence of these things can make people extremely happy.

Q. Returning to the present: what are your thoughts on the crisis in Big Tech?

A. Elon Musk fired three quarters of Twitter’s employees, but the company’s still running. Everyone knows that Big Tech is full of lazy workers, because [the companies] are so profitable that they can afford it. Management has been very generous over the years – whether you work or not, it doesn’t matter, take it easy. Now, due to Elon Musk’s extreme discipline and attitude, these companies are [firing people] like a gesture, to show that they’re making an effort. The truth is that in every company, school or community, at least 10% of personnel are unproductive.

Q. What do you think about ChatGPT?

A. My professor at MIT, Marvin Minsky (one of the pioneers in AI research), always said it’s better not to do business based on [AI]. But now, it’s becoming very popular. The most advanced country is China, while the United States is desperately trying to catch up. I don’t know what will happen, but ChatGPT is still very dumb. When I read the texts it produces, I always laugh. That being said, it’s only a matter of time… machines will become very smart in 10 or 20 years. Personally, however, I’m not very interested. I still have about 20 years of work left and I want to dedicate half to IoT and half to supercomputers.

Q. What do you have in mind for supercomputers?

A. Many people read and hear about supercomputers, but hardly anyone has touched them, because they’re incredibly expensive. If you could produce one for the price of a car, everyone could use it. Perhaps we would not have one in every home, but we would have one in every university or laboratory. Incidentally, supercomputers still use the Fortran 77 [programming] language, which is 45 years old. We need to bring them closer to people, so that they can think about new languages for AI.

Q. Are you still learning?

A. I had to drop out of university because I had to start my company. When I was able to, I tried to return, but the university system didn’t allow it. Finally, I finished my PhD at the age of 60 and was offered a teaching position at the University of Tokyo. I’ve been teaching for five years. Now I have to retire, but I’ve decided to build my own university by investing all the money I have. I hope to achieve this by 2025 – it will be my biggest challenge. Innovation does not depend on physical age, but on mental age and heart. Youth isn’t a specific period of life – you can stay young by changing the way you think.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.