Virivores, the organism can eat up to a million viruses a day

The existence of these microbes is essential to understanding the role of viral particles in the life cycle

There are plants that digest amphibians, fish that feed on algae and viruses that infect bacteria. But among the relationships between predator and prey, there is one that is barely known, and it could be essential to understanding the life cycle.

These are the virivores. As their name implies, they sustain themselves on a diet of viruses.

While the term doesn’t officially exist yet, a group of American researchers have discovered two groups of microorganisms that are neither animals, nor plants, nor fungi – but neither are they simple bacteria. While they are not the first virus-eating organisms to have been identified, they are apparently able to survive and thrive exclusively by feeding on viral material.

Over the last three years, a group of researchers from the University of Nebraska have been studying viruses from a different perspective: not as pathogenic biological entities, but rather, as basic nutrients in the life cycle.

Next to aquatic bacteria, viruses are the most abundant organisms on earth. With so many of them, it’s normal for organisms across the board to ingest them. But John DeLong – a biologist at the University of Nebraska – has tried to demonstrate that there are at least two types of truly virivorous beings that can survive solely on a diet of viruses.

“Several studies had already documented the consumption of viruses,” DeLong tells EL PAÍS via email. “But to our knowledge, it’s the first time that pure [virus consumption] has been demonstrated in these two species.”

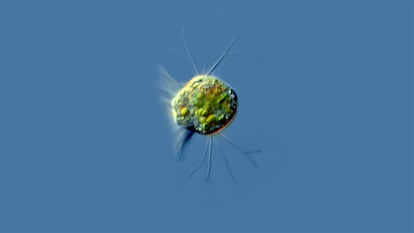

The two species studied are aquatic: Paramecium bursaria and Halteria sp. They were suspected of eating viruses, although it was not known if they were doing so by accident. DeLong’s team has observed them in a laboratory, under controlled conditions. Thus, within small droplets of water obtained from a pond, they released large amounts of chlorovirus – a relatively large virus that infects the chlorophyll of algae in lakes and freshwater reservoirs all over the planet.

After 24 hours, the researchers carefully studied the water droplets. The results of the experiments – published in the scientific journal PNAS – showed that, in the presence of both species, the amount of virus in the water was reduced by up to 100 times. What they needed to confirm was whether the organism had actually eaten the viruses.

Using a staining technique (adding dye for contrast), they turned several of the viruses fluorescent. They subsequently observed them, coming to the estimate that each Halteria sp. was capable of ingesting between 10,000 and a million chloroviruses per day. After a further 48 hours of exposure, they confirmed that the population of Halteria sp. Had increased, while the amount of chlorovirus was drastically reduced. In numbers, the viral load plummeted 100-fold in just two days, while the population of the protista – with nothing to eat except the virus – grew an average of 15-fold over that same period of time.

“We think that viruses are probably very nutritious, having high levels of protein and phosphorus,” DeLong explains. A study on the composition of viruses published a few years ago mentions that they contain nucleic acids, lipids and amino acids. In the case of chloroviruses, they could also contain carbon, which they steal from the chlorophyll of the algae.

Ecologist Joshua Weitz co-authored the latest study about what’s in viruses. Weitz – who leads a group of researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology – has also published several papers on the role of viral entities in the cycle of life.

In an email, Weitz argues that “viruses are potentially nutritious if swallowed by a microbe that digests them and is not infected by the virus.” In general, viruses are made up of genetic material (DNA or RNA).

“Because viral genomes are relatively densely packed – and because genetic material is rich in phosphorus – viruses have higher phosphorus content than typical microbes. Therefore, they might have a nutritional bonus.”

The fact that there are microorganisms that eat viruses forces biologists to reexamine what they know about the life cycle. Viruses – upon infecting all kinds of living beings – burst, releasing organic matter and nutrients into the atmosphere. Now, as Weitz points out, “this research is an important step in advancing our understanding of the ways in which viral particles are involved in moving energy (and nutrients) both up and down microbial food webs.” That is, the role of viruses in the food chain of microorganisms.

DeLong cautions that quantifying the role of viruses as transmitters of energy and nutrients will not be easy. But he sees a lot of health potential in this process.

“If you multiply a rough estimate of how many viruses there are, how many ciliates there are and how much water there is, we would get an enormous amount of energy movement (in the food chain).”

He estimates that organisms in a small pond can gobble up 10 trillion viruses a day.

“If this is happening on the scale we think it could be happening, it should completely change our view of the global carbon cycle.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.