Two meteorite impacts expose the secrets of the inner structure of Mars

A spacecraft reveals new crater measuring about 492 feet in diameter. At the edges of the hole, the white glow of at least a ton of ice can be clearly seen

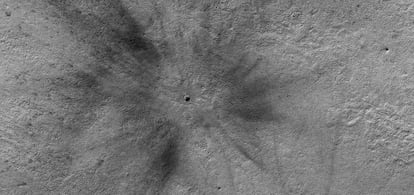

Last year, at the stroke of midnight on Christmas Eve, a lone space probe perched on the surface of Mars recorded one of the largest marsquakes ever detected on the red planet. The tremor was a very shallow one. The people responsible for this NASA mission, named InSight, alerted their colleagues in charge of the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), another US spacecraft that orbits the planet. The images taken by this spacecraft revealed a new crater measuring about 492 feet in diameter in Amazonis Planitia, a vast plain in the northern hemisphere of the red planet, more than 2,000 miles northeast of the probe. At the edges of the hole, the white glow of at least a ton of ice, revealed by the impact of an asteroid, could be clearly seen. That was the first time such an event had been recorded live beyond Earth.

Geophysicist Doyeon Kim is part of the team that analyzes the signals captured by InSight every day in search of new marsquakes. After they realized that they had detected seismic waves caused by an impact, they examined the previous data and found that another one had happened just 94 days before. In that case, the orbiting probe also discovered a crater of about 426 feet in Tempe Terra, 4,600 miles northeast of the ship.

Liliya Posiolova, a scientist who works with the MRO, explains the importance of the finding: these are the largest impacts ever detected by a seismometer and documented with images anywhere in the Solar System – including the Earth. Posiolova and Kim are the first authors of two studies that describe the finding in the journal Science, and NASA explained the discoveries recently in a press conference.

According to their calculations, the Christmas Eve meteorite measured between 15 and 40 feet in diameter. It left a 69-foot crater — the height of a seven-story building — and the energy it released was similar to that of the atomic bomb that devastated Hiroshima in 1945. The magnitude of the quakes caused by this meteorite and the previous one was 4 and 4.1 on the Martian scale, which is similar to that used on Earth, explains Kim.

Most experts believe that if there is life on Mars it has to be underground, safe from the high radiation of the surface. Technically, these two impacts could have uncovered microbes, but there is no way to confirm this, as the craters are thousands of miles away from the robotic spacecraft that are on the planet.

Bombs on the Moon

At the beginning of the 1970s, NASA astronauts detonated bombs on the Moon to study the crust of the satellite through the shock wave that was transmitted through the ground. Those explosions left craters less than 100 feet deep. However, until now, natural tremors had never been detected outside the Earth. The two marsquakes were much more powerful than those recorded decades ago on the Moon, and propagated much faster through the planet’s crust; this made it possible to study the subsurface, up to a depth of about 18 miles, with unprecedented detail.

The new data could clarify one of the red planet’s biggest mysteries: the so-called Martian dichotomy. The two hemispheres of this planet are so dissimilar that they actually look like the halves of two different oranges. The south is a high plateau riddled with meteorite impacts, while the north is a much lower, flatter region. One of the current hypotheses is that shortly after the planet was formed (about 4.5 billion years ago) a giant asteroid over 620 miles in diameter shattered the northern hemisphere, bringing out the magma and creating the current depression. This, in turn, helped an enormous ocean form on this half of the planet. Mars was a blue planet, like Earth, which for reasons still unclear lost almost all of its water and protective atmosphere. Another possibility is that the dichotomy is the result of internal geological processes.

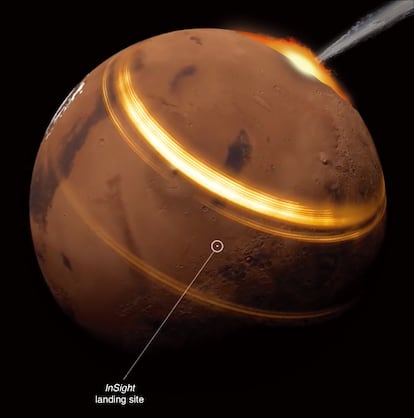

The InSight landed near the Martian equator in November 2018, and since then it has recorded more than 1,000 quakes. Until now, almost all of them came from inside the planet, which has helped the scientists explore its different layers vertically, right below the ship’s sensors. The results have confirmed that Mars has a similar structure to Earth, with a core of about 1,118 miles in radius, a mantle of about 930 miles and a crust of about 31 miles. The marsquakes caused by asteroids, on the other hand, allow the composition of the crust to be studied in detail.

The surface seismic waves caused by the two 2021 meteorites spread in all directions. On the flank closest to the InSight they only crossed the northern hemisphere, while on the other they circled the entire planet. The propagation speed of the seismic waves was very similar in both directions, which means that the Martian crust has a similar composition in both hemispheres.

Simon Stähler, a geophysicist at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School and lead author of the studies, explains that these data suggest that the dichotomy is not a sign of different compositions, but rather that the crust is thicker in the south (about 44 miles, similar to the one in the Himalayas, the highest mountain range on Earth) than in the north (about 19 miles, similar to that of Europe). However, it is still too early to know the implications of these results.

Volcanic activity

Most of the marsquakes captured by the probe occurred in the Cerberus Fossae, a tectonic depression ridden with cracks about 620 miles long. The team has analyzed more than 20 quakes in this area. Most likely, they explain in a third study published in Nature, is that they happened due to magma infiltration. This is quite unexpected, as Mars was thought to no longer be a planet with such activity. Stähler explains that they believe that this volcanic activity happened in the last 50,000 years, which in geological terms is akin to saying “yesterday.” This means that there could be new activity in the near future, and this region should be considered an active volcanic zone.

All of these findings come just as the InSight is about to expire: after almost four years on the red planet, its solar panels are covered in a fine layer of Martian dust that threatens to leave it without power. Stähler estimates that it has a month or less to live.

Meanwhile, the insides of Mars continue to roar. In May, the probe detected the largest marsquake to date; the first with a magnitude of five. Had it been caused by an impact, it would have left a crater of about 656 feet, but the MRO has not seen anything, explains Stähler. The scientist thinks that it was probably a shallow crust quake, but they are still putting all the pieces of information together to find out exactly what happened.

Antonio Molina, a geology expert at the Center for Astrobiology in Madrid, highlights the relevance of this work, particularly the detection of ice on the slopes of one of the craters. The finding is important because it proves that there is water beyond the poles and close to the equator, even with such an arid surface. This is crucial information for future manned missions.

Jens Ormö, a crater expert, explains that, until now, meteorites of this size were thought to hit Mars once every 10 years. So even if the probe stops working soon, the mission has been very lucky to capture two impacts in just one year, he concludes.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.