Australian Indigenous Voice referendum: Denial of the horrors of colonization buries the injustices of the past and of the present

A plebiscite to give new political rights to Aborigines has led to a misinformation campaign against the First Nations people of the island-continent

The journey of Homo sapiens to Australia at least 50,000 years ago remains one of the great mysteries of mankind. Why did our ancestors reach the immense island continent earlier than they did Europe, which is much closer to Africa? How did they navigate the vast oceans? What kind of boats did they use? Bill Bryson summarized this unsolvable problem in his hilarious travel book Down Under: “One of the most momentous events in the history of mankind took place at a time we can only imagine and by means that are hard to believe. I refer, evidently, to the appearance of man in Australia.”

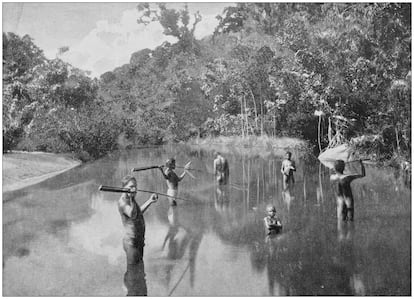

We still don’t know how they did it, but archaeology proves that they arrived, multiplied and populated an unfathomable territory. That is the first great mystery. The second is why other humans did not return to Australia for thousands and thousands of years, until the English captain James Cook reached its shores in 1770. Then, the original inhabitants of Australia, the Aborigines — the oldest continuing human civilization — suffered a cataclysmic physical and cultural extermination. They never regained their rights, and they are still fighting for them today.

On October 14, a referendum is to be held in Australia that would amend the Constitution to give the First Nations people a say in legislative and governmental decisions that affect them. It doesn’t sound particularly revolutionary: in Finland, for example, there is very similar legislation for the Sámi. However, polls indicate that, barring surprises, the “no” vote will prevail due to a terrifying campaign of disinformation against the Aboriginal people. Again, this is nothing new: until 1971 the first inhabitants of Australia had no political rights — they did not even appear in the national census — and their children were systematically taken from their families to be educated in white schools, a period that is known as The Stolen Generation. Today they represent 3.8% of the Australian population, but the rates of incarceration, alcoholism, and poverty among Aborigines are devastating.

The British brought not only bad food to the Antipodes, as Bryson jokes, but annihilating colonization. Their aim was unique in human history: they did not intend to occupy Australia, but to turn it into a vast prison. Robert Hughes explains in The Fatal Shore, one of the great books on the history of Australia, that “that coast would witness a new colonial experiment, unheard of until then. An unexplored continent would become a prison. The space surrounding it, the air itself, the sea, the whole transparent labyrinth of the South Pacific, would become a wall 22,000 kilometers thick.”

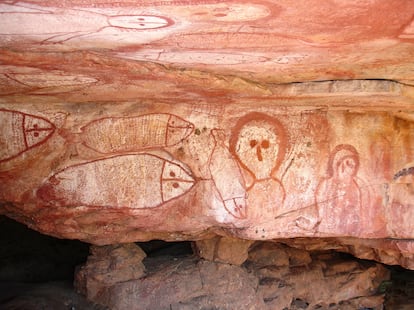

That plan, roughly equivalent to establishing a penal colony on the Moon today, involved the extermination of the Aborigines. “The Australians were divided into tribes,” writes Hughes, of their situation when the British arrived with their minted lamb and their storm of destruction. “They had no notion of private property, but a clear consciousness of territory, for they were bound to their ancestral lands by totemism.” The island continent was interconnected by invisible maps in the form of songs, which were handed down from one generation to the next for millennia — what Bruce Chatwin called The Songlines in his celebrated travel book of the same name — and which are still preserved: that is why the Aborigines are considered to be the oldest culture of humankind. The thread that links their traditions with the past is still alive (which does not mean that it is not also in constant evolution).

The extermination was slow — because Australia is immense — but relentless. The last uncontacted Aborigines emerged from the Gibson Desert in 1984, two centuries after Cook’s arrival: they were the survivors of a systematic and cruel annihilation. “The idea of regarding them as subhuman lasted well into the 20th century,” Bryson writes. “Where Aborigines survived, they were treated most ruthlessly.” Many series and films portray the marginalization in which they remain stranded today, from the crime thriller Mystery Road to the political drama Total Control or Redfern Now, based in a Sydney neighborhood where many people of Aboriginal descent live. Sweet Country, an Australian western drama, is set during the height of the extermination.

More and more historians are revisiting the history of the West by taking into account the horrors of colonization, such as slavery and the subjugation, exploitation, or extermination of Indigenous populations (usually all three at once). This view that angers the right wing in the United States, which has turned the conquest of America into a fairy tale. Denialism arises not only when past injustices are denounced, but also those of the present, as evidenced by the storm of lies and hatred that has been unleashed against the Aborigines simply because they are trying to recover a small fraction of the rights that were stolen from them 200 years ago. As a character in the novel The Sentence by Louise Erdrich, an American writer of Ojibwe origin, says: “A people who see themselves primarily as victims are doomed.” Aboriginal people and Native American people are not willing to be doomed again.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.