What your Tinder photo says about you: ‘In the end everyone looks the same’

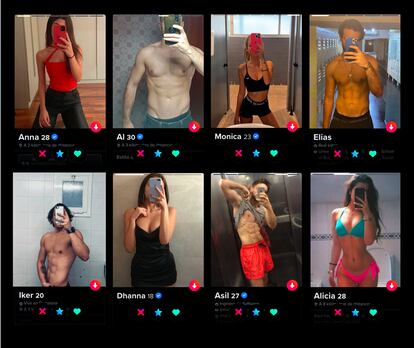

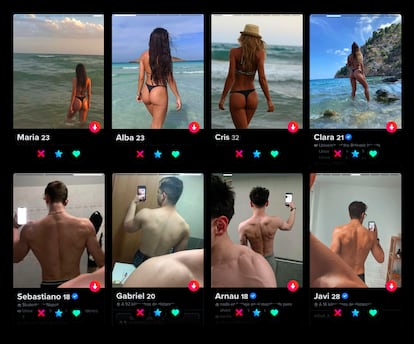

The artist Matilde Duarte has gathered hundreds of Tinder portraits that confirm that when trying to find love and stand out from the rest, the app’s users are resorting to looking as similar as possible to everyone else

Nothing encapsulates the paradoxes and contradictions of our societies as accurately as dating apps. Through Tinder and other apps such as Bumble and Grindr, concepts such as desire and shame, privacy and intimacy, or rules and dissent can be investigated. It can also be explained how platforms are demanding increasingly larger portions of our attention or that, despite the use of the label “middle class” as a catch-all category into which anyone can fit, social classes still exist and habits and customs still mark us as members of one or another.

Furthermore, with its match mechanics, Tinder is a practical demonstration of the idea sociologist Eva Illouz develops in The End of Love. In contemporary societies the negative choice has replaced the classic choice based on selection. Or what amounts to the same is that when faced with an excess of possibilities, today we choose by process of elimination, that is, by sliding left.

Perhaps because the use of these applications generates such varied questions, analysis of them seems go beyond literary genres and has something of a personal chronicle, an art project, or an essay about it. This is the case of Love me, Tinder, by Estela Ortiz and Nuria Gómez Gabriel. In it the authors highlight that, although the male profiles on Tinder are apparently infinite, they present so many similarities between them that all that potential variety can be grouped into just 10 categories. So, although dating app developers claim to promote diversity, in practice users of dating apps end up building very similar profiles. The result is that, in such a mimetic environment, the freedom for those who choose is very reminiscent of that which Eduardo Galeano spoke of when referring to capitalism: a choice between the same and the same.

Something similar has been noticed by the artist Matilde Duarte, who has just launched Match: A Visual Study of Representative Self-display in Tinder Profiles, a book that features 1,572 profile photos taken from the app. They are grouped according to poses and scenarios and the compositions and gestures are, as the title of the publication already warns the reader, very repetitive. There are dozens of ship’s bows, sunsets, and climbing walls.

“At the end of the day, Tinder photos are a reflection of what there is, of what already exists,” explains Duarte. “So the phenomena that appear in the app can be observed in other places, such as in a shopping center where people of the same social class acquire the same goods and services with a feeling of freedom that I couldn’t tell was real or for appearances. It is something that the philosophers Horkheimer and Adorno explain: people with the same model of car, or the same purchasing power, usually meet in identical hotels, have very similar conversations, and discover that as their isolation grows, they become more and more alike.”

Photography has now been democratized thanks to mobile phones with integrated cameras. It is a practice that serves as an “index and instrument of social integration” as stated by Pierre Bourdieu in A Middle Art, his 1965 essay. The French sociologist argues that “in addition to the explicit intentions of the person who took it, even the most insignificant photograph expresses the schemes of perception, thought, and appreciation common to an entire group.”

So, if the mechanisms behind dating apps serve to explain many things about ourselves, the photographs we upload to them are even more eloquent. Even more so because they are portraits. The artistic genre is one that has evolved the most over the centuries, adapting throughout each era to certain cultural conventions that continue to exist. What is not so clear is that finding the love of your life is as easy as applying those unwritten rules about framing, composition, and fit.

The democratization of the portrait and the pose

Tatiana Sentamans is a professor at the UMH Arts Research Center and believes that if we often do not notice the particularities or the symbolic load of the images that surround us, it is because “photography is something that is embedded so well into all levels and in all social strata that, for all of its visibility, it ends up becoming imperceptible.” That is why she argues that it is advisable to be critical of images no matter where they come from, especially because behind the apparent spontaneity of any photograph, there are always codes.

“Homogenization has been connected with categories defined by visual codes for a long time and that are intertwined with complex cultural contexts for each place and for each moment. Not only can Tinder photos can be grouped, but categories can also be established throughout history because, above all, the portraits tend to be the same,” the expert explains.

So to understand contemporary photography, and that includes the photographs that are prepared and uploaded by anonymous users to their dating applications, it is necessary to start from the pictorial portrait.

“In the past, only members of the royal family, nobles, and some politicians had the right to have their own image that represented themselves. Silhouette cutting was a fun practice, a form of cheap portraiture that was carried out at fairs and celebrations, but it was the technological development of photography that democratized the visual construction of oneself,” Sentamans summarizes.

For example, the fact that people on Tinder or any other medium appear with rehearsed gestures or postures, in other words, they still pose, is one of the most explicit legacies that centuries of portraits have projected onto our everyday photographs. As much as it may seem forced or artificial and although it has not been a technical requirement for decades, we continue to pose.

“The pose is inherent to the portrait,” Sentamans points out. “Firstly because the subject portrayed had to sit or lie down for long hours so that the painter could carry out the work, and then because the photographic devices were enormous and the exposure times were very long. Until certain optics were developed, the person who went to a photography studio had to be motionless and hold a very specific pose. Then, thanks to technological advances, candid photography appeared. The beauty of this kind of photography is that it is captured spontaneously, without preparation, although the photographer has not had time to build their own image, which is what they are looking for.”

Embrace the disorder to talk about yourself

At this point, we already know that nothing is casual in a photograph, not even on Tinder. And although projects like Duarte’s handle profile photos as if they were documentary photography to reach certain sociological conclusions, we must not forget that the first thing those who upload those photos look for is to attract the attention of others.

Following on from that, and to prevent our profile from being discarded in tenths of a second, photographer Lucía Alonso offers some reflections, more as an image professional than as a user who “has barely had good experiences on the app.”

“You have to find a middle ground between the most boring normality and an air of mystery,” the photographer comments. “Of course, I think we should present ourselves as we really are, without leaving too much room for imagination or mystery. That is because if, in the end, a date with a person we have idealized goes wrong, that will frustrate us.”

And as for the images, is there any trick to taking or having good photos taken of us? “The line that previously marked what was a good portrait has now changed,” explains Alonso. “The shots, lighting, and settings have changed, a good portrait can be a bathroom selfie at any bar in town. The technique no longer matters so much as the vibe it transmits. If it talks about you, you look good, and you choose it so that someone chooses you, then it’s okay.”

The photographer insists that perfection or technical expertise is not relevant in flirting photos. Furthermore, these are values that, in general, are priced downwards compared to “2000s aesthetics and ugliness.” “You can see it much more clearly on Instagram than on dating apps. Even in fashion or wedding photography, technically perfect is no longer so popular, we’re looking for fuzzy photos [not very sharp due to the vibration of the camera itself] or that have been taken with a flash that has erased features. We are embracing the untidy, the poorly framed, the messy. And it’s not bad to follow the trend if those things really speak about you.” So Alonso only dares to give some concrete practical advice: “Please, do not upload photos where you have cut out the friend sitting next to you, but whose shoulder is still visible inside the frame.”

As if she were an addicted user, Duarte estimates that she looked at around 50,000 photos in four months to make her selection. “At the end of the research my ability to discern between familiar and unknown faces decreased. In other words: everyone looked familiar to me,” she recalls.

Tinder is very likely the largest collection of portraits in the universe, and they all look so similar that, beyond the similarities in pose and format, it works as a huge proof of everything we have in common. It’s not discouraging: it’s the things that unite us that usually create a match. And, at least today, we can do something different from the 16th-century princesses whose court portraits served as a presentation before the distant king whom they would be forced to marry. We can choose to swipe right.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.