From object of desire to pun: What happened to metrosexuals?

They appeared two decades ago, hydrated, perfumed, waxed and toned. Then they disappeared, swept away by the new masculinities. But they left their mark

Twenty years ago, The New York Times outed the man of the new millennium. Under the headline Metrosexuals Come Out, an unusual masculinity was revealed, one that spent money on moisturizing creams and body lotions, hair treatments and Brazilian waxing, $300 designer jeans and Absolut Vodka martinis. The article described “straight urban men willing, even eager, to embrace their feminine sides,” echoing the old misogynistic/sexist conventionalism. Grooming and worrying about looks had always been, of course, a woman’s thing.

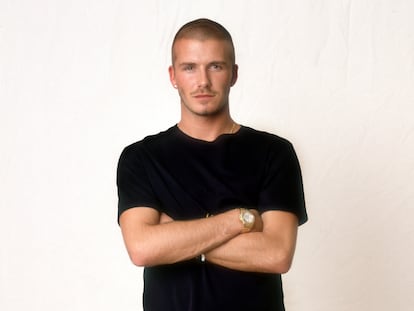

“Even Harrison Ford, whose favorite accessory was once a hammer, now poses proudly wearing an earring,” it stated. It also mentioned David Beckham as an example of a vain guy who was concerned with fashion (surprise, even women’s fashion!) but also capable of maintaining a virile appearance on the soccer field. Thus, the world learned about metrosexuals, observed and dissected in minute detail by the media from then on. Then, just a decade later, they were history. Their ghosts, however, still appear.

A missing link between the Victorian dandy and today’s gym-bro, the metrosexual was a man like no one had ever known. The term was coined by British gay writer and activist Mark Simpson in an essay published in 1994 by The Independent. The metrosexual man was, he wrote, “a young man with money to spend, living in or within easy reach of the metropolis — because that’s where all the best shops, clubs, gyms, and hairdressers are.” Although it is assumed that the term came from the contraction between “metropolis” and “heterosexual,” he always argued that the sexual orientation was “utterly immaterial, because he has taken himself as his own love-object, and pleasure as his sexual preference.”

At a time when in which wearing a Calvin Klein t-shirt — or underpants — could put a man under suspicion of homosexuality (or, at the very least, of having gotten a little off track), the question was then left unresolved. Partly because Simpson’s intentions were actually critical: it was an ironic denunciation of the methods of late capitalism in its eagerness to win over modern man, and how, with the right marketing tools, anything could be sold to anyone.

Time would prove him right, because barely a year after bringing it up again in 2002, with another text for Salon.com (Meet the metrosexual: He’s well dressed, narcissistic and obsessed with butts, but don’t call him gay, which was illustrated with a not quite flattering picture of David Beckham), the men’s cosmetics business appropriated the term with huge benefits. “Back in the dark days of 1994 most metrosexuals didn’t want to confront who they really were. They feared, probably correctly, that their partners and friends wouldn’t understand. Although the media at that time was already full of metrosexual males, all of them were in the closet. There were no open, well-adjusted metrosexuals willing to be role models to young, isolated metros, wrestling with their yearning for scuffing lotion and lycra-rich underwear,” he wrote. Until, suddenly, everyone wanted to be like Beckham. Today, the validation of a man’s body hinges on its desirability (hence phenomena like fatphobia), and male vanity, once an object of ridicule, is now a ticket to fame.

In the 20 years that have passed since the term was taken out of the closet, new models of masculinity have emerged. Still, in one way or another, metrosexuality continues to be present in all of them. It was in the hipster that frequented the barbershop practically every day, devoted to a routine of hydrating beard oil, craft beer and a paleo diet, at the beginning of the last decade. It was in the spornsexual (the ancestor of the gym-bro), another category coined by Simpson to describe the moment, around 2014, in which “sport got into bed with porn while Mr. Armani took pictures.” And it can be sensed in the new fluidity that the fashion industry imposed five years ago, which can be seen everywhere these days among deconstructed gentlemen with pearly fantasy nails, feminine handbags, blouses with bows and skirts, from Harry Styles to Bad Bunny.

“Just gay enough,” they used to say at the time. If the original metrosexuals had understood that gender is just another fiction, we would have been spared so much nonsense.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.