Marx Arriaga: Why Mexico’s top textbook official barricaded himself in his office for four days

The former Educational Materials chief welcomed EL PAÍS into the space, where he held out for nearly 90 hours before being notified of his dismissal

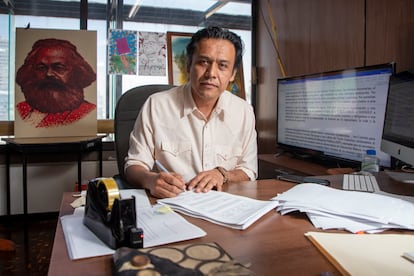

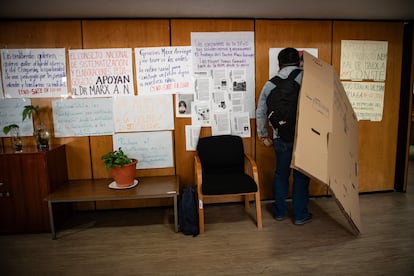

“Thank you, Marx Arriaga, for bringing social critique into the classroom to build a dignified future for our children,” reads one of the 11 signs hanging outside the office that the former director of Educational Materials finally vacated on Tuesday, after four days barricaded inside. Arriaga received and signed the document notifying him of his removal from the post, then walked out of Mexico’s Public Education Secretariat (SEP) in southern Mexico City and headed toward the Coyoacán station on Metro Line 3, accompanied by chants of “you’re not alone.” A couple of hours before leaving, Arriaga — the architect of the free textbooks of the so‑called Nueva Escuela Mexicana (NEM) — received EL PAÍS in a half‑empty office, which was on the verge of being cleared out.

While Arriaga was still inside with five collaborators, movers carried out furniture and boxes with his belongings. The three secretaries in the cubicles outside the wooden doors insisted, “We’re operating normally. Everything is fine.” The reality, however, was that things were not entirely fine.

Since his arrival in 2021, Arriaga had weathered a wave of criticism and lawsuits targeting the textbooks created to educate Mexico’s children and young people. What ultimately led to his dismissal, however, was a request from President Claudia Sheinbaum’s office to include the role of women in history. Arriaga told this newspaper that he “accepts responsibility,” but refused to make the changes because, he said, they did not come from the president herself but from “the sewers” of the Public Education Secretariat.

For four days, he barricaded himself in an office with a desk, two armchairs, a table, four chairs, a couple of cabinets and some books. With a portrait of the German philosopher Karl Marx behind him — which Arriaga tucked under his arm when he was formally notified of his dismissal — he signed the last documents. “I didn’t sleep well. There’s some anxiety. I’m a bit tired, but it’s important to sign these appointments for the contract workers. That’s what we’re doing now. If this isn’t done, our colleagues won’t be able to receive their pay,” he said.

One employee, who preferred not to share his name, recounted that he had accompanied Arriaga years earlier during regional consultation tours for the design of the textbooks. He said he wasn’t surprised by Arriaga’s decision to hold out in the office for days. Still, he added, “Everyone who works in government knows this is a cycle, and that cycle eventually ends.”

As he approached 90 hours in his office, he insisted that barricading himself inside was not an act of personal rebellion, repeating the same message until the very end: “This isn’t a matter of whim.” He added, “I’m an educator, a teacher, and my struggle is pedagogical, not about holding a position. If the new administration has a different educational vision, I’ll go back to training teachers out in the field, in the classrooms. It’s fine.”

Exactly 24 hours before Arriaga walked out of the Public Education Secretariat, Nadia López García had been announced as the person who would take over the post he held for more than five years. “I don’t have the pleasure of knowing her,” he told EL PAÍS. “It’s an administrative decision. Whether she’ll be able to continue the work we were doing here, I don’t know. Each administration charts its own path. The New Mexican School we promoted is a proposal built from the ground up, alongside teachers, shoulder to shoulder, seeking a popular and critical education. One would have to ask whether the new administration shares those principles. If not, the task will be enormous, because they could end up serving other interests.”

On Monday, President Claudia Sheinbaum said during her morning press conference that Arriaga had done “an extraordinary job” with the textbook content. In response, Arriaga said: “She has been very generous in her assessment. We should remember that, in the most difficult moments of the process, when she was head of government in Mexico City, she was one of our main supporters. So I’m deeply grateful for her recognition and her kindness. Our president carries the country on her shoulders, and today she’s fighting to defend workers, the Mexican people, and the economy. That’s no small task.”

Sheinbaum also explained how the dismissal escalated into a conflict. “Marx Arriaga did not agree to any modification of the textbooks. So that’s where the first disagreement arose, so to speak. Faced with that situation, he was offered other options.”

Arriaga has said that, regarding the supposed new job offer, he knows only what has been reported in the media. The president also noted that she disagreed with the way he was notified of his removal and reminded everyone that colleagues must always treat one another with respect.

Regarding the clash over the proposed changes to the content, he reaffirmed his opposition: “Yes, of course I take responsibility. We were opposed when official letters arrived requesting changes. It must be clarified that this was not an instruction from the president, but from areas within the Public Education Secretariat with a vision we consider neoliberal, which have even signed contracts with companies like Coca‑Cola, LEGO and Bimbo.”

He explained to this newspaper that the proposed changes affected the approach he had designed for the project. “They were asking to remove certain content that would have meant a step backward in the educational model.” Among the items that generated the most disagreement, he mentioned those related to historical memory, such as the 1968 massacre, the disappeared, the killings in Ayotzinapa, Aguas Blancas and Acteal, and other episodes linked to what he calls “systemic state violence against dissidents.”

Another employee, who also requested anonymity and stayed with Arriaga in the office for all four days, described the final moments of the official holding on to his post. “We’re waiting for the document to arrive. We’re still working.” The worker had not received any formal notification about the change in leadership and learned of Nadia López’s appointment through social media “just like everyone else.” He is one of the contract workers, with a recently renewed agreement, and is waiting for instructions from the new director.

Speaking about Arriaga, he still referred to him in the present tense: “Since I’ve known him, he’s been someone deeply committed to his ideals. I see him as combative as ever—that’s why I work with him. He motivates me to want to be like that.” As for the reports published in the media about alleged complaints of mistreatment and fee‑collecting from that office, he denied them: “It’s made up. We promised each other not to steal and not to betray, as former president Andrés Manuel López Obrador said.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.