The economic crisis behind protests in Iran: From paying for cooking oil in installments to sleeping on rooftops

Demonstrations in Iran’s streets highlight deep structural discontent in the country, which is facing chronic inflation, widespread poverty, and high youth unemployment

The protests over the past two weeks in Iran highlight a deep and complex structural unrest, in which economic demands represent only the tip of the iceberg.

Although the demonstrations began in Tehran’s Grand Bazaar, the movement stems from much broader causes. Economic factors have always been present in the background of social mobilizations, and this time they have become the main driving force. It is no coincidence that the first spark occurred on December 28 in the commercial heart of the capital and quickly spread to numerous cities across the country, reflecting a widespread conviction that the current system is irreformable.

According to official statistics, over the past eight years, purchasing power has fallen by more than 90%, and the U.S. dollar exchange rate on the open market has risen by 3,300%. This devaluation has been so severe that the toman — an informal unit equivalent to 10 rials — has even begun to be used in official contexts to avoid excessively large figures that are difficult to read and understand. Youth unemployment stands at 19.7%, and a significant portion of those who work do so under precarious conditions. As a result, the middle class, with education, skills, and expectations comparable to those of the global middle class, has been pushed below the poverty line and has lost any prospect of progress. Chronic inflation, officially around 50%, has steadily eroded the social status of broad segments of the population.

In this context, the 67% increase in gasoline prices, along with the controversial budget bill for the coming year, helped ignite the demonstrations. The bill proposes higher taxes and allocates roughly 31 trillion tomans ($365 million) to religious institutions, as well as 210 trillion tomans ($2.32 billion) to the security forces, which constitute the regime’s main repressive arm. Added to this is the elimination of the preferential exchange rate of 28,500 tomans per dollar, previously used to import essential goods such as medicines, food, and medical equipment. These products will now have to be purchased at the open-market rate, close to 147,000 tomans per dollar, meaning their prices could increase fivefold.

As if this weren’t enough, Akbar Ranjbarzadeh, a member of the Parliament’s Industry and Mines Committee, has denounced that “trust companies and exchange houses have failed to deliver $7 billion to the country from oil sales.”

In Iranian economic terminology, trust companies are intermediaries responsible for bypassing international sanctions and transferring revenues from the export of oil and petrochemical products. This opaque network of oligarchs, operating outside the official banking system and the SWIFT mechanism, has repeatedly been at the center of major corruption cases due to the lack of effective oversight.

Over the past decade, the frequency of protests in Iran has increased significantly, reflecting growing social discontent, the gap between the ruling elite and the general population, and widespread rejection of political Islam. The current economic problems are the result of years of internal mismanagement, systemic and uncontrolled corruption, limited foreign relations, and international sanctions — factors that have brought the economy to a near point of no return, making everyday life nearly impossible.

However, these protests are not limited to economic issues: they link the struggle for survival with deep frustration over the lack of freedoms, costly and fruitless regional ventures, and the systematic repression of any critical voice. The regime no longer has the tools to meet the population’s legitimate demands, as any concession would mean admitting the serious flaws in the ideological foundations on which it has relied for more than four decades. For this reason, repression has become its only response.

Karim Sadjadpour, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, has described the Islamic Republic as a “zombie regime.” “Its legitimacy, ideology, economy, and leadership are dead or dying,” he argues. “What keeps it afloat is lethal force. To survive, it kills; and it lives to kill. Violence may delay its demise, but it cannot bring it back to life.”

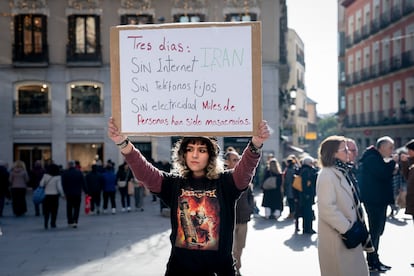

The current shutdown of the internet and telephone communications is tangible proof of this repressive trajectory, aimed at blocking the flow of information, as are the deaths of thousands of protesters.

For Generation Z youngsters, the continuation of this inefficient and repressive system means losing living standards and future prospects; for workers and the most vulnerable sectors, it is a struggle for mere survival. According to the moderate news agency ILNA, which specializes in labor and economic issues, the sharp rise in housing costs and the decline in purchasing power have given rise to the phenomenon of “sleeping on rooftops,” as some people are forced to rent out the tops of houses. Meanwhile, the new agency Tabnak reports a significant increase in the consumption of subsidized bread. Online sales platforms now offer basic products like cooking oil with installment payment options, while many households have drastically reduced their protein intake.

Social outrage intensifies as the public observes how, in the midst of the crisis, oligarchs and the power-connected minority urge the population to embrace austerity and endurance, all while shamelessly flaunting their wealth and lifestyle on social media. The same officials who demonize the West and its symbols have their children living in Europe, the United States, or Canada, enjoying a way of life that openly contradicts the values they profess.

The Islamic Republic was established in 1979 with the promise of protecting the disadvantaged, distributing wealth fairly, and guaranteeing human dignity. However, by 2026, it has flagrantly transformed into a crony capitalist system based on favoritism and nepotism, where the powerful trample on citizens’ rights to protect their hold on power. This double standard has turned poverty into political anger, which Iranians now openly express in the streets.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.