Alissumoye Diedhiou, a Senegalese queen 2.0: ‘I recognize that I was a victim of early and, in a way, forced marriage’

The sovereign of Usui, a traditional kingdom in the south of the African country, focuses her mandate on defending the rights of girls

Enthroned at just 14 years old, Alissumoye Diedhiou has just celebrated a quarter of a century on the throne of Usui, a traditional kingdom in southern Senegal. Her reign focuses primarily on guaranteeing the rights of girls, perhaps because she herself identifies as a victim of early and forced marriage, despite the honor she feels at having been chosen queen by the ancestors of the community.

She greets us at her home while briskly tidying the small living room that serves as an anteroom to her bedroom. Nothing in her modest quarters suggests that Alissumoye Diedhiou (Cabrousse, 1986) is the sovereign of the approximately 50,000 people who inhabit the kingdom of Usui, in southern Senegal. Photographs of her enthronement in 2000, portraits with her husband, King Sibulumbaï Diedhiou, and other images of her surrounded by smiling young people hang on the walls. A large flat-screen television plays a Nigerian romantic drama.

The queen quickly prepares for the interview: she dons a traditional dress and a crown of beads and shells, worn as a sign of respect. In one hand she holds a royal scepter made of cow’s tail; in the other, a state-of-the-art mobile phone that keeps ringing.

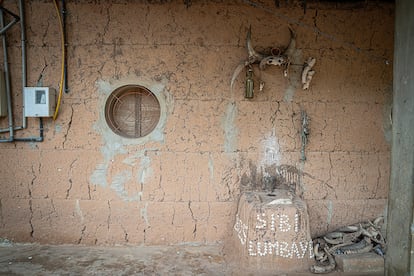

Before departing for the sacred grove, she bids farewell to the king’s three other wives. Only she holds the title of sovereign, but they all live together on the sprawling mud-brick estate, adorned with charms and posters. The one at the entrance announces a breast cancer screening campaign under the slogan “Pink October.” This is how Alissumoye Diedhiou lives, and this is how she reigns: navigating between respect for ancestral customs and a touch of modernity in keeping with the times, within one of West Africa’s most enduring and renowned traditional societies.

Question. You have been the queen of Usui for a quarter of a century, having acceded to the throne at a very young age. What is your assessment of these past 25 years?

Answer. The early days were very complicated. I was very young and didn’t know what a monarchy was: we hadn’t had a king for 16 years, since the previous one had died in 1984 and I was born in 1986. Through a dream, my ancestors told me that I was chosen for this position, which was ratified by the Usui royal council shortly after the enthronement of King Sibulumbaï Diedhiou in 2000. At first, I wasn’t prepared for the life I was given; I was very young. I was already a mother at 16, and then pregnancies followed one after another as I learned to be queen. One of my duties is to listen to the people. At first, when someone came to tell me their problems, I struggled to manage my own feelings, and their stories affected me deeply. I also had to learn to look older people in the eye, before whom, out of respect, a young woman should lower her gaze. Today I feel strong and at peace with myself, and I feel that there is no difficulty I cannot overcome. In 25 years I have accumulated many experiences that have strengthened me, although we continue to face difficulties.

Q. One of the cornerstones of your mandate is your commitment to the rights of girls and women, both within and outside your community. What are your main demands in this regard?

A. I was married very young, at 14. It’s not an appropriate age for marriage, even though it’s culturally accepted here. I recognize that I was a victim of early and, in a way, forced marriage. That’s why I’m committed to caring for girls between the ages of nine and 25, supporting their education and making them aware of their rights. We discuss these issues among sisters in an association we have called Batuyaay, which in our Diola language means “sisterhood.” We talk openly about issues that concern them and for which we sometimes struggle to find answers: life is constantly changing, and we must learn to adapt to the times without losing sight of our principles. I also support them with their schooling, especially those who live outside the villages and have difficulty accessing school. Internationally, I’m a UN Women Goodwill Ambassador committed to fighting child marriage and female genital mutilation, as well as other forms of violence against women. I consider this to be part of my role as queen.

Q. What is a typical day like in the life of a queen?

A. Normal (laughs). In the past, the queen lived with a retinue of young women who took care of her daily needs. But things have changed, and like any mother, my biggest concern is that my children study and have everything they need. So I lead the life of a housewife, an ordinary Diola woman: I sweep, I wash dishes, I pound rice, I cook… I combine that with my duties of receiving people who come to tell me about their personal or social needs and of performing sacred ceremonies in the sacred grove with the king. I live between my house’s courtyard and the royal palace.

Q. How do you survive financially?

A. Neither the king nor I receive a salary, and we live austerely. We live on what people give us, and we must manage it responsibly, prioritizing the health and education of our children, since in a time of financial need, it wouldn’t be right to have to ask for money. There have been times when I’ve struggled to make ends meet.

Q. The Kingdom of Usui, comprising 22 villages, is an international benchmark for managing contemporary challenges from a traditional perspective. The king’s directives, always reached by consensus, are followed without hesitation by the population. Could you share some of the strategies you and your husband use to achieve this?

A. Our primary mandate is to guarantee social cohesion and peace. In our community, we encounter all sorts of conflicts: territorial, agricultural, familial, or neighborly, including thefts or disputes between ethnic groups. Our population also faces significant economic challenges, so we collectively cultivate rice to distribute to those most in need. When people experience conflict, we listen to them and engage in dialogue without prejudice. When someone makes a mistake, they must apologize to the community. Our traditional religion provides us with tools for managing these conflicts, primarily through prohibitions or taboos (ñi ñi in Diola) and moments of communion through the veneration of our gods. Personally, as the moral authority of this royalty representing women, I ensure that nothing said will offend or hurt them.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.