The last tomb keepers

In Santiago’s General Cemetery, tradition links the dead and their families to those who care for their graves

Among the tombs in Santiago’s General Cemetery, the appearance of bouquets of flowers, some of them dry, others fresh and vibrant, indicate the amount of time that has passed since someone visited the deceased. Near the entryway on Recoleta Avenue, the least touristy section that does not feature the imposing mausoleums of yesteryear, 72-year-old Ana Muñoz cleans and sometimes decorates her section of tombs. Before she did this work, her mother was in charge of the same patch of earth, and before her, her grandmother. Muñoz’s ancestors has cared for this place of rest, for the same families, generation after generation. The cemetery and the majority of those who work in it are under the purview of the Recoleta municipal government. But caretakers like Ana belong to another tradition, one that links the dead and their families to those who maintain the resting place for their remains. Grandmother, mother, and daughter have been here thanks to payments from the families whose graves they care for. It is their vocation.

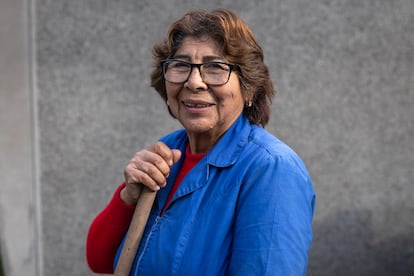

Muñoz wears a blue jacket, black stockings and gray shoes. She was born in November 1952 and is the caretaker for a small area of the cemetery. At the beginning of the 1930s, her grandmother Carmen took over the maintenance of the section thanks to a reference from a friend. Muñoz describes her grandmother as a self-sacrificing and courageous woman who lived a few minutes away from the cemetery. Her nine children attended school nearby and after class, came to the tombs. “My mother Flor María and my aunts and uncles grew up here,” says Muñoz.

When Carmen died in the mid-20th century, Flor María took over her work. She was already married and had started a family, and Muñoz and her three siblings — two sisters and a brother — also grew up among the tombs helping their mother, who Muñoz remembers smoking one cigarette after another. She was the only one who carried on the family legacy. November 1 and Mother’s Day were the important dates when it came to agreeing on contracts with the families who owned the tombs. “The families knew that my grandmother had been the caretaker,” says Muñoz. In 2015, her mother got sick. From that point on, Muñoz gradually started taking over her duties. At first, she only came on Fridays. Later, she added more days. Now, she’s been working full-time in the cemetery for 14 years, from Monday to Saturday. She prunes, waters, cleans, and maintains the graves.

“Today, far fewer people come than before, because today there are more cemeteries,” says Muñoz, whose mother died two years ago. The area she cares for is not very large. It is located near Limay Avenue, in the cemetery’s 95th courtyard. Her office is a shed stocked with different gardening tools, like watering cans made from plastic bottles, pruning shears, shovels, brushes, gloves and rakes. Lastly, a gas stove, to warm up her lunch, which is important because the cemetery has no electricity. “I water, prune, sweep, and accompany them,” says Muñoz. She lives four subway stations away and arrives every day at 9 a.m. She leaves around 3 p.m., because in the afternoon, and particularly at night, this is a dangerous place. “They have robbed pieces of tombs and even assaulted family members,” she says as she sits to rest on a small wooden bench she brought from home.

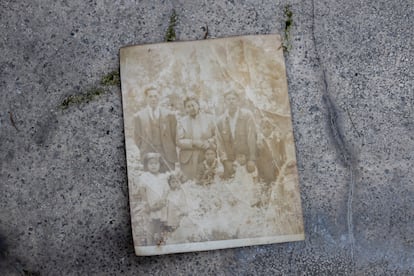

An older man appears carrying some bags and the two greet each other. It’s her 63-year-old cousin Miguel Mateluna, who is also a caretaker, just as his parents and grandparents were before him. Hortensia, his mother, was Muñoz’s first cousin. “My grandmother Otilia was the first to work in the cemetery,” says the man, showing an old, yellowed photograph taken in this very section of the cemetery, in which appear his grandparents and his mother when she was a little girl. Mateluna cares for around 40 tombs in the 91st patio, behind an old mausoleum of the Spanish Mutual Aid Society. When he was young, he always helped his parents. “I got married and had two children, but I never stopped coming,” he says. “He gets here first, at eight in the morning,” says Muñoz. They keep each other company during the day, and always eat lunch together.

Their payment varies by family because they negotiate their terms “directly with the owners of the tombs,” in contrast with the cemetery workers, who are employed by the Recoleta municipal government. Muñoz says that sometimes families miss weeks or months of payments, depending on the whims of the person paying and how often they visit their loved ones. What they charge depends on the agreement with each client, but it ranges between $10 to $15 a month. “Are you going to put more potatoes into the stew?” was the phrase his mother used to close the negotiations with the owners of the tombs, whose payments never fell below $3 a month. “I can’t speak for all the caretakers, but I almost always earn less than minimum wage” ($529 a month), says Muñoz, who cleans around 50 tombs, all of which have been bought in perpetuity. “I get a message that says, ‘Ana, I sent you the payment for May’ or ‘OK Ana, I sent you a deposit for three months,’” she explains. When a lot of time has gone by without receiving a payment, the woman stops caring for the tombs. “This isn’t free,” she says.

The cemetery’s current administration, which was installed last March, says that they are putting together an official registry of the caretakers, and estimate that there are around 200, 90% of which are women. The caretakers are not General Cemetery employees. They work autonomously and have no official duties, hierarchy or salary, clarifies the administration. Legislation prevents cemetery officials from intervening with the tombs without permission, because when they are sold they become property of the families. Unless there is obvious risk of danger, they are only allowed to clean the streets and pathways.

Despite this autonomy, the caretakers’ union has made advancements via a representative who negotiates their demands with the cemetery’s administration. Some of these include the construction of the metal sheds to store their belongings and the tools they use on a daily basis, exemption from paying burial fees for a plot in the earthern courtyard for five years, and the option of free cremation. The administration even says that they have the right to hold their own funeral and mass at the cemetery chapel, an exclusive benefit for caretakers that is not even extended to cemetery employees.

Muñoz has three children. They’re all professionals, and have made a life for themselves away from the cemetery, unlike previous generations. It’s the same with the family of Mateluna, who is the father of two daughters. “They studied, they got ahead and they’re not thinking about working here like us,” the two caretakers say. They have no plans to abandon the family business in the country’s largest graveyard. But they know that the caretaking tradition will die with them.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.