Cristina Kirchner and 86 other defendants face the biggest corruption trial in Argentina’s history

Former officials and business leaders will be tried in the so-called ‘notebooks case’ involving an alleged bribes-for-contracts scheme between 2003 and 2015

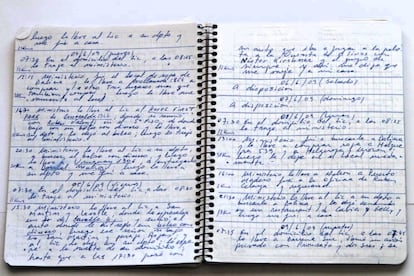

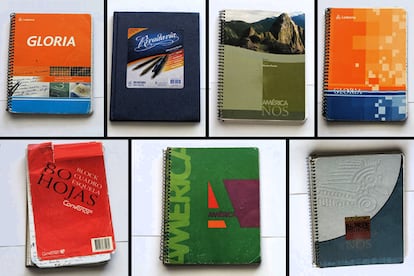

For nearly 12 years, Oscar Centeno, the driver for a high-ranking official in the governments of Néstor and Cristina Kirchner, meticulously recorded every trip he made with bags full of cash, the proceeds of alleged bribes paid by construction companies in exchange for government contracts. He detailed schedules, routes, names—and even the weight of the bags when he couldn’t calculate how many dollars they contained.

The notebooks in which he recorded all these trips were the starting point of the investigation that has led to the biggest corruption case in Argentine history: the so-called “notebooks case.” On Thursday, the trial begins against Cristina Kirchner as the alleged head of an illicit bribery ring, for which 19 former Kirchner administration officials and 65 businesspeople, among other defendants, will also stand trial.

The 72-year-old former president is already serving a six-year prison sentence in a separate corruption case and has been under house arrest since June. She now faces potential sentences of between five and 10 years. Her defense maintains that “the sentence has already been written” because it is “a witch hunt” and “an act of revenge,” according to Gregorio Dalbón, Kirchner’s lawyer.

According to the prosecution’s indictment, the former president and her husband, the late Néstor Kirchner, organized between 2003 and 2015 “a fundraising system to receive illicit money in order to illegally enrich themselves.” To this end, they established “agreements with prominent businesspeople from national and international companies, through which they obtained reciprocal benefits.” The prosecution alleges that “the leaders and organizers of this para-state structure designed a money-raising circuit focused primarily on the awarding and granting of public works contracts and/or services, and other related benefits.”

The legal case centers on the payments made to business leaders, detailed in the notebooks of the chauffeur Centeno, the schemes used to award contracts for rail transportation and highway projects, and the cartelization of public works. In addition to Kirchner, the charges include former ministers, secretaries, undersecretaries and state directors, as well as Centeno himself and another former driver, and executives of major construction, energy, and transportation companies.

The trips documented by Centeno—who was the driver for an undersecretary at the Ministry of Federal Planning—came to light in mid-2018 in an investigation by Diego Cabot in the newspaper La Nación; at the same time, the journalist provided the courts with photocopies he had of the notebooks. The detailed scheme of Kirchnerist corruption hinted at in those notes was confirmed in the following weeks by several of the businesspeople mentioned in them. They agreed to testify as cooperating witnesses in exchange for leniency.

Most of the repentant businessmen said they paid money to Kirchnerist officials, but denied that it was in exchange for public works contracts. According to their testimonies, the funds they handed over were intended to finance the ruling party’s election campaigns and were in fact forced contributions obtained through extortion. This was the version given to the court by the repentant construction magnate Angelo Calcaterra, cousin of former president Mauricio Macri, and also by Aldo Roggio, owner of one of Argentina’s largest business conglomerates, Grupo Roggio.

Other defendants, however, admitted to the systematic payment of bribes for contracts. Carlos Wagner, the former head of the Argentine Chamber of Construction and owner of the construction company Esuco, provided the court with a list of companies that, through the Chamber, paid sums of undeclared cash to obtain infrastructure contracts. He also stated that the illegal fundraising system had begun during the presidency of Néstor Kirchner (2003-2007) and had continued during the two terms of his wife and successor, Cristina Kirchner (2007-2015).

Years later, some repentant businessmen changed their story and requested the dismissal of their charges, claiming they had confessed to paying bribes under duress from Judge Claudio Bonadio, who died in 2020. Construction company owner Mario Rovella declared before a notary in 2023 that he lied in his court testimony to avoid prison, since Bonadio was ordering pretrial detention for those who did not admit to the alleged crimes attributed to them, while releasing those who adhered to the “plea bargain” program.

Last September, the accused businessmen attempted a final maneuver to avoid trial. They offered the court sums of money totaling up to $15 million, and even a Miami apartment and a yacht, to be released from the case. Prosecutor Fabiana León listened to the offers and categorically rejected them: “There is no price that can be put on the institutional damage that has been caused.” Days later, the court ruled in the same vein and rejected full reparations, considering that “corruption crimes affect supra-individual legal rights that cannot be compensated solely with money.”

During the trial, it is presumed that the defendants’ lawyers will challenge the authenticity of the notebooks, the central evidence in the case. Kirchner’s lawyers have already unsuccessfully requested the dismissal of the case because two expert analyses detected numerous alterations, erasures, and corrections made by other people in Centeno’s notes. Last week, the Supreme Court rejected more than 20 appeals filed by former officials and businesspeople, paving the way for the trial to begin.

Illegal financing of politics

The significance of the trial goes beyond the alleged corruption during the Kirchner administrations, according to experts. “What’s at stake is that, for the first time, what we all knew was going on behind the scenes is being discussed publicly,” emphasizes Pedro Biscay, founder of the Center for Research and Prevention of Economic Crime (CIPCE). “There’s an underlying phenomenon: an institutionalized system of illicitly financing politics,” Biscay continues.

This lawyer specializing in corruption cites the exclusion of Techint executives from the trial as a prime example. Techint is Argentina’s largest economic group. Centeno’s notebooks record nine trips to the steel company’s headquarters. Even so, the initial charges were dismissed by the investigating judge, who accepted that Techint executives delivered money “for humanitarian reasons” to evacuate employees from Sidor, the company’s Venezuelan subsidiary, which had just been nationalized. “That a judge would dare to say this explains that there is a pact of corruption in Argentina,” he argues.

In theory, Biscay points out, this trial offers the possibility that “not only will some corrupt individuals end up in prison, but that this criminal market will be weakened.” In practice, however, he sees it as more difficult due to the complexity of a mega-trial with almost 90 defendants.

Martín Astarita, senior researcher at FLACSO’s Center for Studies on Corruption, Integrity, and Transparency, also emphasizes the importance of scrutinizing the role of businesspeople, who have often been relegated to the background in previous cases. “Corruption must be understood as a highly damaging relationship between the public and private sectors,” says Astarita. In his opinion, in recent years there has been a growing capture of the public sector by the private sector, which has gone almost unnoticed by the justice system.

The trial will be conducted primarily through virtual hearings, broadcast via videoconference. More than 600 witnesses are expected to testify, and the trial could last up to three years.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.