Judges in Nicaragua now answer to police under Ortega and Murillo’s rule

A circular requires courts to seek authorization to carry out seizures, property occupations, or evictions, effectively subordinating the judicial system to the regime

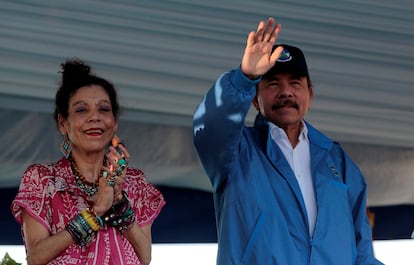

Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo have dealt a final blow to what remained of judicial independence in Nicaragua: the presidential couple has stripped judges of their authority and subordinated them to the National Police — headed by their son-in-law, General Commissioner Francisco Díaz — when it comes to the seizure and confiscation of assets and property.

A police circular dated early May but made public this week states that any court order involving “seizures, occupation of property, or evictions due to debts must first be approved by the police leadership,” which, in practice, strictly follows the directives of Ortega and Murillo. Property seizures have become one of the regime’s primary tools of repression against any citizen deemed to be an opponent.

“This directive is not only another link in the chain of authoritarian control, but it also openly violates Nicaragua’s Constitution,” says Juan-Diego Barberena, a lawyer in exile in Costa Rica.

Article 167 of the Constitution states that “the rulings and resolutions of the courts and judges must be unconditionally obeyed by state authorities, organizations, and individuals.” Yet now, the police leadership stands above the judiciary in executing confiscations — something officers had already been doing without judicial authorization.

“Commanders, before executing court orders involving seizures or evictions due to debts, the operation must be authorized by the undersigned and C.G. Victoriano Ruíz Urbina,” reads the document’s first clause. Ruíz Urbina is head of the Judicial Assistance Directorate (DAJ) and oversees El Chipote prison, the Ortega-Murillo regime’s main torture center.

The internal order was distributed to all police delegations and specialized units across the country, making it clear they must not act on any judicial mandate involving seizures or evictions without prior approval. The circular also restricts enforcement of arrest warrants in cases involving property crimes like fraud or double-dealing (e.g., selling property already ceded), even if issued lawfully by judges.

“The police are positioning themselves above the judiciary, nullifying the courts’ authority,” Barberena tells EL PAÍS. “What are the legal implications of this? It dissolves the judiciary’s ability to enforce rulings. That, in essence, is the main responsibility of justice systems. Or, in other words, it reflects the fact that power is no longer subject to the law, and that there is no rule of law in Nicaragua.”

The police’s official justification is the need to “assess” the individuals involved and analyze the territorial situation. In practice, however, this gives officers the unconstitutional power to decide whether to comply with a judicial order.

“The political filter of justice”

While the justice system was already answerable to Ortega and Murillo, and was far from impartial, the new procedure, according to another lawyer who asked to remain anonymous, turns the police into “a political-administrative filter of justice.”

“This practice could lead to a system of selective justice, in which the execution of court orders depends on political interests or alliances with those in power,” the lawyer explains. “Cases of land dispossession, illegal occupations, and debt disputes might no longer be resolved in the courts, but rather in police offices based on criteria of convenience.”

The circular is part of the Ortega-Murillo regime’s broader campaign to assert total institutional control. Just nine days after the police directive was issued, the National Assembly — entirely controlled by the ruling party — fast-tracked a new Judicial Career Law that effectively eliminated merit- and exam-based appointments and promotions within the judiciary. It also stripped the Judicial Branch of its power to independently appoint judges, magistrates, clerks, and legal advisors.

In other words, it solidifies the political subordination of the entire justice system, which since a sweeping constitutional reform in February — ordered by Murillo and Ortega — ceased to function as an independent institution and became “a body coordinated” by the executive branch.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.