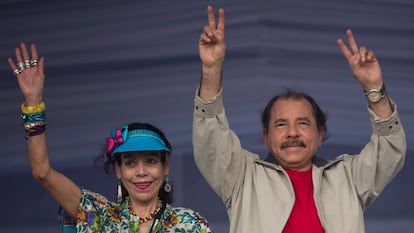

A ‘tropicalized Taliban regime’ and a family succession plan underway: Ortega and Murillo radicalize repression in Nicaragua

Six years after the massive protests of 2018, the system remains unchanged, political violence has increased and all opposition groups and dissenting voices have been silenced

Since 2018, the Nicaraguan police have stepped up repression every April, when citizens and government opponents commemorate the mass social protests that broke out against the regime of President Daniel Ortega and his wife, Vice President Rosario Murillo, and were crushed by a brutal paramilitary and police crackdown. This year is no different. Police have detained five people and increased their activities in the country’s main capital cities. The individuals arrested are relatives of protesters who died in the police crackdown and released political prisoners.

Since the social unrest of 2018, the political violence in Nicaragua has continued unabated. After six years of a sustained sociopolitical crisis, the regime is still capable of shocking the people with the extent of its terror: on Tuesday, April 15, the body of government opponent Carlos Alberto Garcia Suárez was found in the municipal dump of the city of Jinotepe. Ninety percent of his body was burned, completely scorched.

García Suárez was imprisoned during the 2018 protests for allegedly committing the crimes “of kidnapping, torture, assault, injuries and illegal possession of weapons to the detriment of the state and Nicaraguan society.” In other words, the 52-year-old political prisoner — a shoemaker by trade — was one of the thousands of citizens in Jinotepe who participated in the street barricades against the Sandinista regime. The police said there was no “criminal hand” behind the death, but the Former Political Prisoners Reflection Group (GREX) argues there are many inconsistencies in the police version of events. For example, the last time García Suárez was seen alive was this April 13, but the authorities reported that the body was in a state of “skeletal decomposition.”

“No corpse reaches the level of skeletal decomposition in two days. Everything that is coming out from the police and Forensic Medicine has no credibility,” says Ricardo Baltodano, one of the directors of GREX. “We want to highlight that he is the third former political prisoner to be murdered in a heinous manner since 2021, and there is no in-depth investigation. The government is the main suspect, but this is to send a message to the former political prisoners that they should tread carefully.”

Baltodano is referring to the terror gripping Nicaragua, one of the main pillars of the regime. However, it is not the only thing that has allowed the Ortega-Murillo family to maintain its iron-fist rule, despite the political challenges they have suffered nationally and internationally.

Six years since the 2018 sociopolitical crisis — a watershed moment for citizens that put the president and vice president on the ropes — the Ortega-Murillo regime’s well-oiled system of represssion persists, with money to run the country, and a dynastic succession plan in the works.

“Nicaragua has changed a lot since 2018,” Manuel Orozco, a political scientist at the Inter-American Dialogue, tells EL PAÍS. “The country went from a political crisis fighting to democratize and dismantle a nepotist infrastructure, to a tropicalized Taliban-style radicalization regime, supported by five pillars: criminalizing democracy and the Constitution; control of the State; fear with violence; international isolation and post-truth to guarantee the consolidation of a dynasty.”

The regime’s repression has dismantled every type of political and social organization in Nicaragua, including NGOs, media outlets, political parties, universities, peasant movements, environmentalists, feminists, critical businessmen and, recently, even the Catholic Church. What’s left of the opposition in Nicaragua is tiny. These groups operate in complete secrecy, and have zero margin for action. Nicaraguans have become used to living in fear and silencing their criticism of the government in order to survive. This, however, is still no guarantee that they won’t end up in prison, exile or, in the worst-case scenario, dead in a garbage dump.

These violations “have caused, and continue to cause, multiple additional human rights violations which are so far-reaching that they are impossible to quantify, thereby demonstrating the authorities’ intention to relentlessly incapacitate any opposition in the longer term,” the Group of Human Rights Experts on Nicaragua said in their latest report. What’s more, in addition to their absolute control of society, the Ortega-Rosario regime is preparing the family succession.

All signs indicate that Laureano Ortega Murillo, the opera-loving son of the presidential couple, is next in line. In 2012, his parents appointed him “presidential advisor for the promotion of investments, trade and international cooperation.” But it’s in the last two years that he has played a greater role, so much so that in December 2023, he appeared before a delegation of the Chinese Communist Party as “special representative of the secretary general of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN).” Only his father has ever held this position in the party. His mother, Rosario Murillo, the powerful “co-president,” is orchestrating the transition plan from behind the curtains.

“The dictatorship is consolidating itself. I do not agree with the optimistic messages that the dictatorship is in decline. What they are doing is cleansing themselves of internal adversaries, as they did with the purge in the Supreme Court of Justice, to then launch the line of succession, which is first Rosario Murillo and then Laureano,” says Eliseo Núñez, a former opposition deputy, who was stripped by the regime of his Nicaraguan citizenship.

Failings of the opposition

Political repression has hit the opposition hard. Within Nicaragua, the opposition has been devastated by exile and prison. In February 2022, the regime banished 222 political prisoners, including opposition candidates for the presidency. Spread out largely between the United States and Costa Rica, the opposition has become caught up in internal differences that have stopped it from creating a single bloc. These long-standing disagreements have prevented the opposition from presenting themselves to Nicaraguans and the international community as a reliable alternative to the Ortega-Murillo regime.

“In the political archipelago of the opposition and the diaspora there are more than 250 parties, which compete to issue statements, and not for political action,” says political scientist Orozco, who was also stripped of his nationalitiy. “It is a movement that is hijacked by political reductionism and terrible historical thirst for revenge on the part of the loud-speaking minority. They reduce alliances to non-existent ideologies and demand revenge for an unfinished history. Meanwhile, Nicaraguans are not looking back at what happened 40 years ago, whether they like it or not. They are looking at the present and politically what they are clear about is democracy and not repetition, but they are not talking about right-wing democracy and revenge.”

Orozco insists that, despite the ideological differences that have hampered the unity of the opposition, the common denominator remains the same: creating a coalition with the capacity to achieve change, and with the capacity to govern democratically. That requires, he adds, “ousting the dictatorship from power; governing democratically; justice without impunity and a truth commission.”

Former deputy Núñez — who is part of Monteverde, the most solid opposition movement today — speaks of the need for self-reflection. He talks more about “personal responsibilities than organizational responsibilities.”

“It is an opposition of personalities without organic structures [...] and it has not been understood that the key is to organize. Some continue to operate from pedestals and, at certain times, offer magical solutions. So the few organizations that exist are attacked because they are very left-wing or very right-wing. The opposition in Nicaragua has a difficult time because it does not have a base on which to build itself, unlike in Venezuela, where political parties still have a certain capacity. In Nicaragua, since even before 2018, political parties did not have any capacity.”

The economy still works for the regime

The last issue that has helped the Ortega-Murillo family stay in power is the economy, which still works for the regime. Núñez explains that Nicaragua is a small country, but it is able to survive on little. That’s why the enormous injection of dollars from family remittances has been able to revive the market. In 2023, remittances to Nicaragua hit a record high: $4.66 billion, a year-on-year spike of 44.5%, which meant an additional $1.44 billion dollars compared to 2022.

“Since the protests in 2018, the country has had no possibility of making major changes in the economic matrix, nor of exponential growth. Ortega cannot do more than what he is doing, which is a very conservative economic policy. He is accumulating money by increasing revenue at the expense of pressure,” says Núñez. “This is comparable to the Taliban government, which has managed to raise revenue. But the fact that revenue is increasing does not indicate that you have been successful, but rather that your extortion model is working and has limits. That’s why some companies in Nicaragua have closed.”

The Sandinista government has also continued to receive loans from multilateral organizations, such as the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI). The country’s main trading partner continues to be the United States and the Ortega-Murillo regime has also become closer to Russia, Iran and China.

“It is a tactical self-isolation [in which Nicaragua has aligned itself] with aggressor states and the fact that it has been maintained is accidental: debt and remittances. Both add up to 35% of national income, plus foreign trade that does not affect transnational capital,” adds Orozco. The political scientist believes that reviewing the Free Trade Agreement between the Dominican Republic, Central America and the United States (CAFTA-DR) — which does not currently have a clause to expel countries that violate human rights — is a key way to weaken the Rosario-Murillo regime.

Experts agree that, as long as these conditions are maintained, the Ortega-Murillo regime will continue to be there, ruling and filling the country’s prisons with political prisoners, in an endless revolving door. As of April 2024, 138 citizens are in prison for political reasons, according to the Mechanism for the Recognition of Political Prisoners.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.