The illegal adoption business in Chile is not only about the dictatorship

A journalistic investigation — conducted via dozens of reports — illustrates the irregularities in the system, with cases dating back to 2024

Jocelyn Koch Aguilera and her mother, Jacquelin Aguilera Betanzo, are sitting at a small table in the café of the Memory and Human Rights Museum in Santiago. The museum is dedicated to those who disappeared during Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship (1973-1990) in Chile.

The table is completely covered with legal documents. Three folders contain more than 500 pages of reports, statements and court orders. Jocelyn and Jacquelin — like the women who took to the streets to protest during the military regime — are also searching for a disappeared person. But in their case, this tragedy has nothing to do with the dictatorship, the extrajudicial killings, or the clandestine torture centers. The two women are searching for Kevin — Jocelyn’s younger brother — whom they last saw in 2004, when he was given up for adoption.

For years, the two women have been denouncing the numerous irregularities that occurred during the boy’s adoption. It all began in 2003. Jaquelin was going through a period of profound financial and personal hardship. She requested to temporarily place her two youngest children — Jocelyn and Kevin, who were six and two-years-old at the time — in a foster home, so that she could look for work and more stable housing. Jaquelin had been a victim of domestic violence for years and had just moved to the city of Concepción from Santiago, after her last partner began using drugs. “I couldn’t support my children, so I temporarily left them to the state. But I never thought this decision would involve my son being adopted,” the 61-year-old woman laments today.

Jaquelin hoped that the two children could be placed in the same home. However, they ended up being separated. The eldest, Jocelyn, was sent to the SOS shelter in Lorenzo Arenas, while Kevin — just two-years-old — was entrusted to the Arrullo Orphanage. Both foster homes were based in Concepción. “In Kevin’s case, it was always different,” Jaquelin recalls. “Every time I went to see him, he cried desperately, saying that he wanted to live with me again and that he didn’t want to be in the home. The psychologist and social worker who were following our case constantly told me I wasn’t capable of raising my son.” This was not the case at the home where Jocelyn had been sent.

The Arrullo Orphanage was at the center of a major scandal in 2011. And, in 2013, it was investigated by a commission of inquiry established by the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of Chile’s Congress. This was after a report by a Chilean radio station revealed a series of child abuse cases occurring within the residence.

As soon as Kevin entered the home, Jaquelin was included in an eight-month program in which a team — consisting of a social worker and a psychologist — would shadow her, in an attempt to help her and assess her abilities as a mother. The documents collected by Jaquelin and Jocelyn include records of visits to the orphanage, which show that Jacquelin visited her son regularly, at least once a week. Then, Jacquelin recalls, one day out of the blue, in 2004, she went to the home and one of the staff members informed her that the boy had been declared eligible for adoption. Along with two other children, he had been taken away in a white car. However, the mother claims that she had not received any formal notification of the Chilean court’s decision.

From that moment on, she heard nothing more about her son. Everywhere she went, the authorities told her that they knew nothing. Jaquelin fell into a severe depression, from which she struggled to emerge. And, while Kevin was given up for adoption because the Chilean government deemed her unfit to raise children, in 2010, her daughter, Jocelyn, left the foster home where she was living and was — once again — entrusted to her mother.

“Why did the Chilean government take a son away from her — after deeming her unfit to be a mother — when she was then deemed fit to raise me, just six years after Kevin was given up for adoption?” Jocelyn wonders aloud. From the moment Jocelyn left home, she went everywhere with her mother looking for her brother: the two women knocked on every door, even going to the airport to try to find out if he was adopted by a foreign couple.

After many attempts, they managed to locate the psychologist who had followed Kevin’s case at the Arrullo facility, who told them to forget about it, that Kevin was fine. She even advised the mother to “see a psychiatrist to get over the situation.”

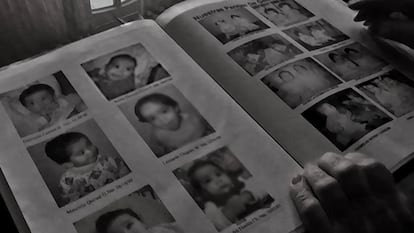

On the pile of documents the two women have compiled over the years — which attest to the irregularities that occurred during the adoption process — there’s a framed photo of Kevin. In that portrait, he’s a smiling child. And, more than 20 years later — for Jocelyn and Jaquelin — Kevin still looks that way. They don’t know what he looks like today. They don’t even know if he’s alive or dead. For them, Kevin is that old image, crystallized in time. Jocelyn, now 27, has a tattoo on her forearm: it depicts her and her brother embracing. “I just want him to know that he’s my greatest treasure and that I’ll never stop looking for him, as long as I live,” she says quietly.

20,000 illegal adoptions

Almost a decade ago, a major scandal erupted in Chile, which has become an internationally-known case. This had to do with the approximately 20,000 adoptions carried out during the Pinochet dictatorship. The estimate came from a judge — Mario Carroz — who opened the first case back in 2017. He currently sits on the Supreme Court.

The Chilean justice system and a brigade of the PDI (the country’s investigative police) have been investigating the matter for years. However, due to a major justice reform, both teams now only handle cases occurring up to 2004. Complaints related to subsequent years are referred — separately — to the Carabineros (the National Police) or the Ministry of the Interior. Therefore, there’s no Chilean public entity that investigates complaints of irregular adoptions that occurred over the last 20 years. And, for this same reason, there are no official figures regarding how many complaints have been filed since 2004. The justice system has never investigated to find common patterns or charge alleged perpetrators.

In recent years, however, dozens of public complaints have been filed about illegal adoptions across Chile. They involve children who, in most cases, were adopted by European couples.

During this investigation, EL PAÍS has compiled dozens of reports of illegal adoptions in various parts of the country, with cases dating back to 2004. These adoptions occurred during the current democratic era and were always managed by SENAME, the National Children’s Service. This Chilean state entity handles everything related to minors, including adoption. For years, SENAME has been at the center of enormous controversy, due to the numerous irregularities detected in its management.

The most serious known case is that of the horrific abuse suffered by minors in the foster homes managed by the entity. This scandal came to light after the publication of an investigation conducted by the PDI in 2017. The report revealed that in 100% of the 240 homes investigated, minors had suffered abuse. A total of 2,071 children were harmed, 310 in a sexual manner. And, every year in Chile, new scandals erupt. These are primarily related to child prostitution rings, in which those responsible for the foster homes force the minors in their care into prostitution. This is according to many of the complaints filed by parents with the PDI and reported by local media outlets.

While the country’s adoption system has undergone profound revisions and improvements since the dictatorship, there are anomalies and operating procedures that seem to have never changed, from the 1970s to the present day. The affected families are always poor and the cases often involve single mothers from marginalized areas. Parents are not notified of their children’s eligibility for adoption, visits to the institutions are arbitrarily prohibited and children are given up for adoption abroad without prior verification of the presence of other relatives in the country who could take care of the child, as stipulated by law. This is not to mention the various institutions that, despite having racked up dozens of complaints since the 1970s — and despite being under investigation by the PDI and the Chilean justice system — continue to be accredited by the state.

In 2020, Kevin’s alleged illegal adoption was reported to a prosecutor by Patricia Muñoz, a Chilean lawyer who was appointed as Chile’s first Children’s Ombudsman from 2018 to 2023. She now states: “I’ve reported several cases of irregular adoption, while many others have been brought to my attention. These were completely flawed processes in which the biological parents had no chance of regaining custody of their children. These are families who received absolutely no help from the state and only learned later on that their children had been given up for adoption.”

Between 2010 and 2020, 70% of Chilean children adopted outside the country were adopted by Italian families. Italy and the United States are the two major receiving countries for international adoptions, but in Chile, Italians clearly hold the top spot: there are seven accredited Italian childcare institutes, five of which are currently operating.

Between 2010 and 2020 — according to data provided by SENAME — a total of 4,512 children were given up for adoption in Chile, of which 844 were adopted by foreign couples. The people who adopted Chilean children between 2010 and 2020 hailed from a variety of nations — including Spain, Denmark, Australia, the United States, Belgium, New Zealand and Sweden — while the countries that received the most children were Italy, Norway and France. However, the number of children adopted in Italy was clearly higher during that 10-year period: between 2010 and 2020, 587 Chilean children arrived in Italy, while 95 arrived in Norway and 91 in France.

Among the cases analyzed throughout this investigation, there are several in which women turned to the state for protection, reporting abuse at the hands of their partners. But instead of receiving help, their children were stolen from them. This is the case of Giannina Riccardi, now 32. In 2018, after reporting domestic violence, she had her daughter, Ignacia, taken away from her. Ignacia was later given up for adoption.

For years, Giannina denounced the abuse that the girl suffered at the foster home, as well as the irregularities that occurred during the adoption process. In 2020, she created the Facebook page Madres Desesperadas (Desperate Mothers), where she compiled hundreds of reports from across the country. Ignacia was given up for adoption at the age of seven by the Nido de Hualpén, an orphanage which was closed after several parents reported a pedophile ring that paid staff to abuse children.

“I did everything the judge asked me to do to get my daughter back,” Giannina recalls today. “I found a better job, left my abusive partner and rented a bigger house,” she continues. “But after she was given up for adoption, I attempted suicide several times; I once jumped from the fourth floor of my building. I would pass by Ignacia’s room… the pain of not seeing her in bed devastated me.”

In 2014, another mother also publicly denounced the illegal adoption of her children, chaining herself in front of the Puerto Aysén Cathedral and beginning a hunger strike. She also collected dozens of testimonies from other mothers with similar cases in her region. The woman — Yohanna Oyarzo — is now 41-years-old. In 2011, her three sons — Gabriel, Benjamín, and Erick, who were then five, four and two-years-old respectively — were taken from her and later given up for adoption to a French couple. This was despite the protests of their mother, who claims that she did everything the courts had required of her in the previous months to regain custody of her children.

The adoption of Yohanna’s children was carried out by the Eleonora Giorgi Home in Puerto Aysén. This facility was run by Sister Augusta Pedrielli, a distant cousin of the father of the famous Italian tenor, Luciano Pavarotti. Pavarotti had financed the purchase of the land where the foster home stands. It was shuttered in 2015, following dozens of complaints after Yohanna’s hunger strike.

Sister Augusta confirmed to EL PAÍS that she bought the land thanks to Pavarotti’s donation. Cristina Pavarotti — the tenor’s daughter — also confirms contact between her father and Augusta Pedrielli between 1989 and 1990. She also notes that her father “decided to send three incubators and shoes for the children.”

“At the same time,” Cristina adds, “while I wasn’t able to find documents about the monetary donation that made it possible to acquire the land, I consider it probable. But I can also say that the contact between Sister Augusta and my father was limited to that period of time.”

Yohanna still remembers the hours and days she spent visiting her children. She also remembers the reports about the abuse that her children suffered from. One of them told her that he had been sexually abused by an older girl during his time at the foster home. Today, Yohanna says that “not a day goes by that I don’t think about my children.”

“It’s a pain that will never end. I can only keep going because I have hope that, one day, I’ll be able to hug them again.”

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.