The Bedouin fighting from Israel to get his family out of Gaza’s hell

Two evacuations, from the Sinai and Gaza, and the stigma of betrayal wound up bringing Riad El Shtiwi to a town without a name in the Negev desert

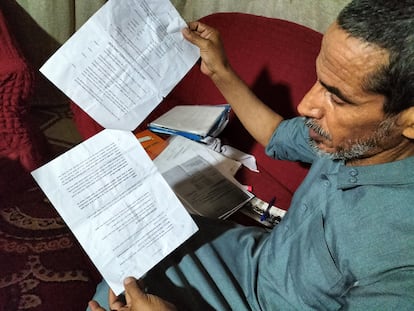

Riad El Shtiwi opens a folder of documents in Arabic and Hebrew, compiled over decades, to explain how he wound up here, while his wife Widad and four of their children (who were born in Israel) are in Gaza, facing hunger and bombings. “Here” is difficult to define: a precarious town in the Israeli desert of Negev that does not have an official name and does not appear on maps, like dozens of other so-called “unrecognized settlements,” most of them Bedouin. It is known as Tel Arad due to its proximity to an archaeological site by the same name that stands some 16 miles from the Dead Sea, although the two are separated by an unmarked dirt road traversed by camels, which have been the family’s mode of transportation on their journey across three distinct territories (Egypt, Gaza and Israel) — a metaphor for half a century of conflict in the Middle East.

In 2005, Israeli authorities relocated El Shtiwi and another 68 families pertaining to the Armilat — a Bedouin clan originally from the northern coast of the Egyptian peninsula of the Sinai — to Tel Arad. They removed them from a place that did have a name (Dahaniya), but that is known in Gaza by another moniker: the “village of the traitors.”

It was built by Israeli military authorities in the 1970s (when they controlled Gaza as well as the Sinai after their victory in the Six-Day War of 1967) to compensate them for having appropriated their land to build the Jewish settlement of Yamit, and for siding with and spying for the Israelis during the conflict. When Israel and Egypt signed a peace treaty in 1987, part of the clan returned to the Sinai. Riad’s family left for Dahaniya, where there was running water, electricity and a half hectare of land per person.

In 1994, when the Oslo Agreement between Israelis and Palestinians began to be implemented, Gaza became (along with Jericho, in the West Bank) the first place to fly the Palestinian flag and Dahaniya became a place guarded by separation barriers and Israeli soldiers. Residents carried weapons at night and an unmistakable breach separated the Bedouins from the Palestinian collaborationists that Israel had relocated to the site during the First Intifada (1987-1993), so that they wouldn’t be assassinated in the West Bank for having shared information with the enemy. Israelis and Palestinians agreed to leave Dahaniya under Israeli sovereignty, “pending a declaration of general [Palestinian] amnesty for the residents of the village.” Such a declaration never arrived, nor were they ever freed from their stigma.

Then in 2005, the government of Ariel Sharon unilaterally decided to withdraw its troops and 9,000 settlers from Gaza, which had become a hotbed of conflict, choosing instead to focus on the West Bank. Images from that time have gone down in history, those of soldiers forcibly removing Jewish settlers dressed in orange, the color of the anti-withdrawal movement. At the time, no one cared much about the fate of the “village of the traitors.”

Although Israel built Dahaniya, they did not include it in the evacuation compensation plan, so its inhabitants received less money than the Jewish settlers. Staying in the new Gaza with their collaborationist stigma hanging over their heads and without the protection of Israeli soldiers was a risky option. Some returned to their homeland in Egypt, and others petitioned the Supreme Court for a transfer to Israel. The case ended up on the desk of Sharon, who decided to grant them a temporary residential permit until “it becomes clear” whether their lives would really be in danger in Gaza.

The military left them near the inhospitable Tel Arad, with tents and a tank truck for water. In stories from this time, the clan’s evacuated members complained about this new life, lacking fertile land to grow for their tomatoes, without even electricity. Not to mention, the truck leaked, so they had to travel miles for water. “They took us back 30 years,” remembers El Shtiwi, as the women prepare the lamb and rice that they will eat for dinner seated on the ground, near the fire.

For the Bedouin families who already inhabited the zone, the tank truck was actually a slap in the face after years of unsuccessfully petitioning Israeli authorities to be connected to water and electrical networks. The Jewish communities nearby were also displeased by the arrival of an “[economically] weak and unemployed population” that “will only increase the area’s crime rate,” as the mayor of the city of Arad, Moti Brill, said at the time. A week later, after sermons against the new arrivals were delivered in local mosques, Bedouins in the area opened fire on their homes. They fled, going back to the border with Gaza, but military authorities were firm: it was Tel Arad or nothing. “They forced us to come back,” Shtiwi laments.

“Now I’m content with being in Israel, I have no regrets. I didn’t want to stay in Gaza or leave [for Egypt]. But I’m also surprised that they brought us to a place where there is nothing, a mile from the main road,” he continues.

Authorities do not recognize Tel Arad nor other nearby settlements (some of which were established prior to the founding of Israel in 1948) in order to put pressure on their inhabitants to move to cities, to give up their traditional way of life. Their goal: free up the territory for the expansion of Jewish towns and military training bases. Since their communities are not legal, neither is construction. “All this faces demolition orders,” El Shtiwi says, gesturing towards two structures. The dynamic stands in stark contrast with the West Bank Jewish settlements that the State of Israel considers to be illegal: it’s quite uncommon for them to be taken down and with the passage of time, they end up receiving protection, funds, war, access roads and public infrastructure.

Today, the Gazan side of the Kerem Shalom border terminal with Israel stands atop the former site of Dahaniya. At one point, it was part of the airport that was briefly located in Gaza, a dramatic symbol of the crushed dreams of the peace process. Built with international funds, it celebrated its first flight with pomp and circumstance in 1998. Four years later, in the middle of the Second Intifada, Israel bombed its radar station and control tower, bulldozing its runway.

Today, El Shtiwi, at 47 years of age, is focused on getting Widad, who he calls his second wife despite their lack of legal status due to Israel’s 1977 ban on polygamy, out of Gaza. Widad, 44, is from Rafah. They got married in 2007 and had three children (today, they are 15, 14 and 11 years old) during a period in which El Shtiwi lived in Gaza. In 2016, when he was in Israel, she entered on a medical visitation permit and took advantage of the opportunity to stay in Tel Arad.

“We built a house and the children studied at the local school,” remembers Shtiwi. They had four more children (today, between three and seven years old) who were born in an Israeli hospital named Soroka and were educated in the country. Two years ago, they were deported to Gaza, on account of their irregular migration status.

Authorities do not look kindly on polygamy, which is practiced by a third of the Negev Bedouins, but is not legal. Shtiwi had to take a DNA test to prove that he was the father of the children and ask for their return. He received the results of the test on October 2, 2023.

Five days later, Hamas launched its brutal surprise attack, Israel began to devastate Gaza and everything (getting someone out of the Gaza Strip, completing government paperwork) became a Herculean task, despite its even greater urgency. After petitions and appointments with the Interior Ministry, on July 29 El Shtiwi submitted his family registration form and says he will receive a response in six months. “Do you realize what six months in Gaza is like right now?” he asks. “Sometimes I think, ‘It’s wartime, it’s complicated.’ But then I realize it’s the other way around. It would take 10 minutes: someone gets them to Kerem Shalom and gets them out that way. Hamas is not going to object,” he says.

Meanwhile, Widad spends her days with her children, living on welfare in a precarious tent near the town of Khan Yunis, after having fled the advance of troops towards Rafah, where at least they lived in four concrete walls. “In Rafah, we were not happy, because we wanted to return to our home in Israel and the children wanted to be with their father. Now we are worse off, in a tent where it is very hot. People ask me, ‘Your husband is an Israeli citizen, why doesn’t he receive you and your children?’” she says via voice and text messages on WhatsApp. “Truly, life is hard.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.