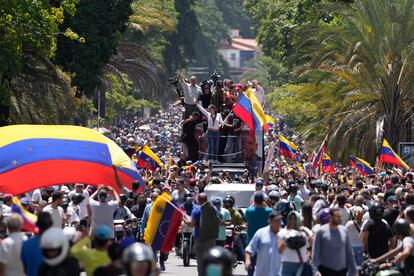

Venezuelan opposition seeks alternatives to make its votes count

Amid a general retreat to alleviate the wave of repression, the opposition has placed part of its hopes on the efforts of the international community

Within the Venezuelan opposition, everybody seems to be aware of the impact produced in national and international opinion by the publication — in view of the lack of transparency of the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) — of the presidential election voting records from the campaign command of Edmundo González Urrutia and María Corina Machado, and the conviction of having inflicted a crushing electoral defeat on Chavismo (67% for the opposition candidate against 30% for Nicolás Maduro), in particularly unequal and atypical conditions, is widespread.

But beyond these conclusions, the prevailing feeling is fear. Politicians are hermetic. Interviews have been cancelled. Members of the opposition leaders’ entourage have changed their telephone numbers. There is extreme caution in WhatsApp groups; Zoom conversations are scarce. Police harass citizens looking for data on their cell phones. Electoral witnesses and voting center officials are judicially harassed. At least two civil activists have been detained at the Maiquetía International Airport. There are many — too many — analysts and observers who prefer to keep their opinions for another time.

Chavismo’s repression in the post-electoral week led both Urrutia and Machado to address the Armed Forces Monday in a joint communiqué, a text the former signed as “president-elect of Venezuela” and the latter as leader of the “democratic forces of Venezuela.” “Do not repress the people, accompany them”, they ask in the statement, in which they insist on the “overwhelming” victory of the opposition candidate and criticize “the brutal offensive” of the Maduro regime against “democratic leaders, witnesses, polling station members and even ordinary citizens.” The missive includes a call to “the conscience of the military and the police to stand with the people and their own families” and abandon the Maduro government.

For his part, the Chavista leader has the arguments against him, but he objectively controls the levers of power. The Venezuelan president has announced that 2,000 detainees will be sent to maximum security prisons for protesting, and affirms that there will be more arrests: “Enough of impunity, fascism is over, do not negotiate with fascists. The people have spoken, and they want peace,” he declared. Maduro has the backing of the Armed Forces and has requested an injunction from the Electoral Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice, before which he has promised to submit the electoral paper vote tallies, which have not yet been published, in order to clarify his proclaimed victory. It is expected that the Supreme Court — controlled by the PSUV — will rule in his favor.

There is, therefore, a strange sensation of paralysis in Venezuela. Few people can forecast what might happen next. Maduro is on television constantly, appearing irritated, threatening, and ready to assert his own version of events. “For the Venezuelan democratic movement, there is only one objective: that Edmundo González Urrutia is proclaimed President of the Republic on January 10 next year,” says Carlos Blanco, an economist, political analyst and strategist for the opposition, as well as a close advisor to Machado.

It is a process that, in Blanco’s opinion, is just beginning and that will face multiple obstacles on the path to an eventual negotiating space in which the international community will mediate. The analyst rules out a transition agreement that would take Machado out of the picture, as put forward in the negotiation promoted by Mexico, Colombia, and Brazil, as reported by EL PAÍS. “María Corina and Edmundo are a binomial. She is the popular engine; he is the candidate. There is no possibility of both acting separately, and even less so now. The idea of negotiating only with Edmundo, without María Corina being present, is absurd. These are maneuvers aimed at creating problems that the opposition has already solved in the past.”

Blanco does not consider it appropriate to wait for the institutions of the Venezuelan state to resolve the problem. “The election has already taken place. The victory was achieved, and they do not want to recognize it. We have to mobilize; it is very important to maintain this enormous support from the international community to exert the necessary pressure.”

For electoral consultant and political analyst Carmen Beatriz Fernández, Venezuela is entering uncharted territory. “There is a lot of hope invested in what Lula, Gustavo Petro and López Obrador can do, perhaps too much.” Fernández believes that the international perception of the opposition’s victory is clear, but distinguishes between those nations that do not recognize Maduro’s reelection on the current terms — such as some European countries — and those that have expressly recognized González Urrutia’s victory, as has been the case in the United States and other Latin American nations.

“That difference is not trivial,” she notes. “It marks different paths in the negotiations over a problem that is already Latin American. Those nations that limit themselves to questioning the result, without admitting the opposition’s victory, could be working on the ground to invalidate the election, to seek an agreement to repeat it, or not to enforce the result, a path that is more comfortable for Maduro,” she adds.

Sociologist and analyst Tulio Hernández considers that the consequence of the electoral outcome does not offer alternative conclusions: Venezuela has entered a dictatorship, and perhaps it is no longer the time to discuss political strategies. “We have left behind the hegemonic authoritarian framework, and we have reached the zone of totalitarianism. An unprecedented process in these dimensions,” he argues. “There are almost no free media left; the government is breaking off diplomatic relations with Latin America; isolation is deepening, journalists are expelled; police officers ask for citizens’ phones, looking for political information. It is the most dangerous, the most serious, the saddest moment of these 25 years [of Chavismo]. The government has renounced any democratic mask. International pressure helps, it makes the problem visible, but, as we have seen, it does not solve it. The only thing left is to resist.”

“I would start with these six words, to lend context: there is no rule of law. It is not easy to talk about what can be done. The political power in Venezuela is doing what it wants. The massive popular support that González Urrutia has is fundamental, but not enough,” says sociologist, academic and researcher Ramon Piñango of the Institute of Higher Studies in Administration.

Professor Piñango maintains, however, that Maduro’s government is not showing signs of strength. “It is not rhetoric to state this. Chavistas did not imagine that they would end up looking so bad. Many of them have doubts about the result. It is not easy for people to assimilate this reality. What has happened in the country affects everything one does. The consequences will be serious, and that is clear to many in power. We are taking it step by step. Here, it is necessary not to rush.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.