The truth about Carlos Lehder, Pablo Escobar’s feared associate

The drug lord recounts his life as a key member of the Medellín Cartel after leaving a US prison, where he served 33 years

The computer screen is faded to black. On the other end of the video call, an elderly man can be heard speaking slowly, respectfully, attentively. Excuse me a moment, Mr. Carlos Lehder, could you please turn on your camera for a few seconds to verify that you are who you say you are? A click sounds a gray-haired guy with a pronounced receding hairline, small eyes and thick nose appears on screen. He wears an orange t-shirt and behind him is a desk, an old armchair and, hanging on the wall, framed black-and-white photos. Lehder has jealously guarded his appearance for nearly four decades. Now, at 74, he looks like a grandfather playing bingo at a retirement home. But he was once one of the most well-known and feared drug lords in the world. An associate of Pablo Escobar, he was a key member of the Medellín Cartel and at the epicenter of the conspiracies of one of the biggest criminal enterprises that has ever existed.

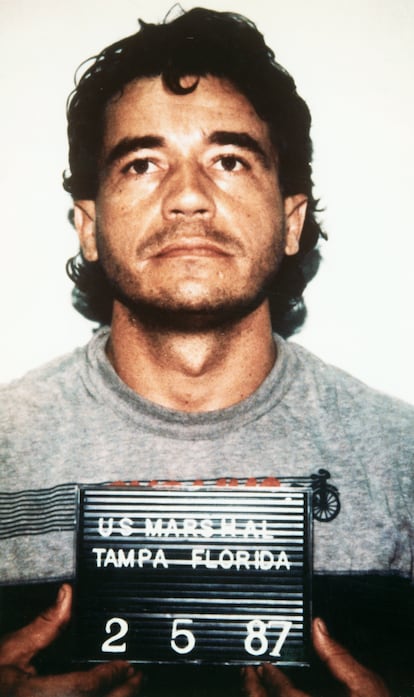

Lehder has been living in Frankfurt since 2020, where he moved after serving 33 years in a U.S. prison. A federal court judge in Jacksonville, Florida, sentenced him to life imprisonment in the late 1980s for running a criminal enterprise, and another 135 years for conspiring to smuggle cocaine into North America. He was held in a maximum-security prison with a brutal regime of solitary confinement that almost broke him, but after testifying against Panamanian dictator Manuel Antonio Noriega, whom he said he had trafficked drugs with Escobar, his sentence was reduced and he was transferred to a penitentiary with fewer restrictions, where he worked in the kitchen. From then on, he dedicated his time to reading and studying, something he had hardly been able to do during his time as a cartel kingpin. Once freed, he began to write a book, Vida y muerte del cartel de Medellín (Life and Death of the Medellin Cartel).

Lehder’s is one of those lives that seems impossible to fit into one. His father was a German engineer who settled in Colombia. He met his mother in Armenia, a city overlooking the Andes. The couple opened a boarding house called La Posada Alemana, which was very popular at the time. As a teenager, Lehder did not want to go into the hotel business or study at university. Instead, he began smuggling stolen vehicles into the U.S., a crime for which he would spend time in a federal prison in Danbury, Connecticut. Upon his release, he set up his own dealership in Medellín — Lehderautos — and began dealing marijuana and cocaine. In his early twenties, he taught himself to fly small planes and became an expert at flooding the United States with drugs. The DEA soon had him on their radar, but because they couldn’t stop him, he became a myth among federal agents.

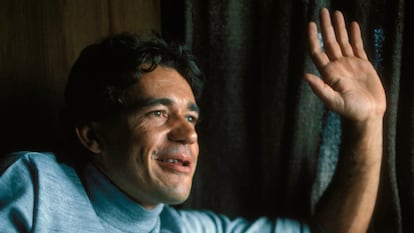

He amassed such a fortune before he was 30 that he bought his own island, Norman’s Cay in the Bahamas. He bribed policemen, ministers, and even the president of the newly independent country, where he built a port and airstrips. An army of mercenaries protected the island and the business. The parties in Norman’s Cay became legendary. Handsome and athletic through his dedication to running and weight training, at night Lehder would party. By day, he patrolled armed with rifles and hand grenades, wearing a bulletproof vest. On one occasion, rival Colombians tried to storm the island and Lehder repelled them with gunfire. There is certainly action in his book, but he portrays himself as a character from The A Team, the 1980s television show where however much gunfire was exchanged, there were never any deaths or injuries: blood is nowhere to be seen. Lehder prefers to describe himself as an armed, rational, good-hearted pacifist, who shows mercy to his enemies.

Those who have researched the history of the Medellín Cartel paint a very different picture. In a vast number of books he is described as impulsive and violent, feared by other drug traffickers. Lehder has had no choice but to confront these dark areas of his personality. Page 370 of his book covers a well-documented crime that everyone who was there at the time attributes to him. It took place at the Hacienda Nápoles, Pablo Escobar’s estate. It was a day of excess, of cocaine and alcohol, which was nothing unusual in the country house Escobar built and filled with hippos, giraffes, and exotic birds. Lehder was with a woman that night, Sonia, who took a shine to Rollo, a handsome Escobar hitman. Lehder flew into a jealous rage, according to a widely documented version, and executed him in front of several witnesses. Lehder has another version of events: it was Rayo — he changes the name in the book — who intended to kill him. What happened then? “I was supposed to die. I didn’t die that day,” Lehder says in the interview with EL PAÍS, a hint of vanity in his voice. In his writing, he acknowledges the crime of omission: “I spotted Rayo, who was walking followed by his rifle-carrying boy and two more gunmen. I concentrated on watching him. After a while, three automatic rifle shots rang out, which sent the pigeons and swallows flying in terror from the roofs of the immense Nápoles house.”

Lehder and Escobar had formed an alliance to do business and oppose the extradition treaty between the Colombian and U.S. governments. They were joined by other capos such as José Gonzalo Rodríguez Gacha — nicknamed “El Mexicano” for his love of mariachis and Paso Fino horses — and the Ochoa family. This was the genesis of the Medellín Cartel. The criminal organization challenged the state with the assassination of the Colombian Minister of Justice, Rodrigo Lara Bonilla, who led an unprecedented offensive against drug traffickers. Lehder says that he did not participate in this conspiracy, although he acknowledges that he celebrated Bonilla’s death and congratulated Escobar on the work of his assassins. He claims that Escobar had Lara Bonilla killed due to a personal grudge and not as an attack on the Colombian authorities. When asked about this, Lehder maintains a heavy silence that lasts for about 10 seconds. He breaks it with a justification: “I did not participate in any assassination or plot. I have chosen to defend my life in circumstances in which it was life or death. But never against the Colombian government.” Throughout the conversation it becomes clear that if anything hurts Lehder, it is accusations of treason against his homeland.

Although he now attempts to put it into context, he was a supporter of the Muerte a Secuestradores (MAS) movement. He wrote a manifesto in its favor that was published in the newspapers. MAS was created by drug lords to persecute the M-19 guerrillas — the organization to which Colombian President Gustavo Petro belonged — who had kidnapped Martha Nieves Ochoa a few days earlier. It was an entente between criminals, police, ranchers, businessmen, and the military that meted out brutal violence in the country, especially against leftist movements. Many consider MAS to be the precursor of paramilitarism in Colombia, which in the following years would be responsible for tens of thousands of murders. Lehder draws a line under the subject in a couple of pages of the book.

During his time as a criminal, Lehder carved out an image of himself as a drunk, crazy, vain, and a fascist. He has been painted as a man with a machine gun on his shoulder and a Third Reich helmet. He asked a sculptor for a life-size bronze statue of John Lennon, one of his idols. “I’m no saint, but I was disciplined and ethical. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have been successful. I was never a drug addict,” he says. Delusions of grandeur led him to create the ultranationalist Movimiento Cívico Latino (National Latin Civic Movement). “It was to denounce that the extradition treaty was illegal and people had to know about it,” he adds. Journalists who followed him say that the movement mixed Nazi and Indigenous ideology and that it intended to become an armed group that would fight the guerrillas in the jungle.

However, Lehder’s killing of one of Escobar’s top hitmen brought an end to their friendship. Lehder became paranoid that Escobar wanted to do away with him — as he had with three other associates — an anguish that was compounded by the persecution of the DEA. He was finally arrested in 1987 and extradited to Florida, thus becoming the first Colombian cartel boss to make that trip. He later learned from his lawyer that it was Escobar who had turned him over to the authorities in revenge. Lehder, who spent three decades behind bars because of that betrayal, has now taken his own revenge in his book, attributing all the crimes committed against ministers, judges, and journalists to Escobar, without exception. The living are those who write history and the dead — Escobar was killed in December 1993 — can only turn over in their graves.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.