The waning legacy of Berlusconi, the first great populist

The political party Forza Italia has broken down, three decades after the famous televised speech given by the late businessman, in which he announced that he was entering politics to change the rules of the game. Today, the party is a shadow of its former self, a minor partner in PM Giorgia Meloni’s far-right coalition government

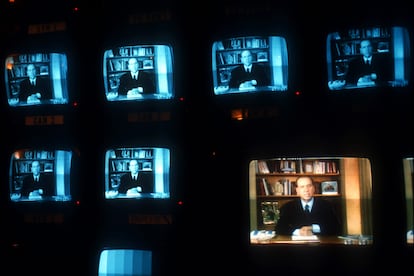

Everything about the video had the air of an experiment, a revolution. Even the invention by director Roberto Gasparotti, who had the idea of covering the camera lens with nylon stockings, to give warmth to the image… and, above all, to make Silvio Berlusconi’s 56-year-old face (still without a trace of plastic surgery) appear younger.

The nine-minute-long speech that was broadcast on the night of January 26, 1994 contained almost everything that would be seen in Italian politics for the next 30 years: a false set, a businessman who became a politician, special effects, soccer analogies — “get out onto the field” — the specter of communism and lots of money from special interests. It was a success.

Berlusconi served as prime minister of his country on three occasions (1994-1995, 2001-2006 and 2008-2011). He was the inspiration for many phenomena that would come about, such as Donald Trump. However, half-a-year after his death – and after 30 years of court battles, sex scandals, economic crises, resignations and decisions that changed everything so that everything could remain the same – practically nothing remains of the phenomenon that was Forza Italia.

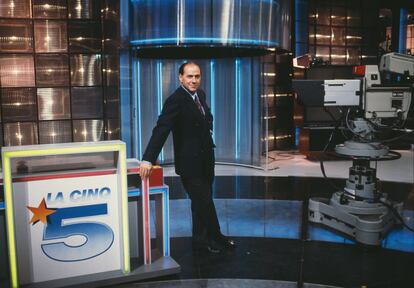

“Italy is the country I love,” the magnate and president of AC Milan then began, looking at the camera. And from there, from that set, he built an unprecedented political vehicle in the southern European country that broke with the old communists and Christian Democrats. Berlusconi quickly attained unusual levels of support and popularity. He built his party, Forza Italia, on the aspirational dreams of an emerging middle-class. And, with that story, he swayed half of Italy. The other half, however, was raised against doing politics in such a personalistic manner.

While he had a big political persona, Berlusconi’s tenure was sterile in terms of overall results. In his almost 10 years of government in total, the country reduced its per capita income by 3.1%, according to the IMF (one of the worst figures in the EU). Consumption fell by 8% and food spending by 36%. Debt went up, but somehow, educational spending decreased by about 11%, while the cultural budget shrank by 30%. Meanwhile, spending on defense grew by 35%.

The risk premium — and a European troika (the IMF, the European Commission and the European Central Bank) whose patience was exhausted — finally brought down his project in the fall of 2011, when the country’s risk premium reached its all-time high of 574 points. Even so, during the years of Forza Italia, Italy became one of the strongholds of the EPP (European People’s Party) in elections for the European Parliament despite having a loose cannon as a leader.

Today, however, Forza Italia, is a shadow of its former self. Polling at around 7%, it’s a minor party in Giorgia Meloni’s far-right coalition. It’s also a symbol of how much the EPP has lost power in countries (such as France) where the extreme right has overtaken it.

It’s true that Berlusconi’s political bloc was always uncomfortable with Christian democratic parties, which mostly make up the EPP. However, as it has sought short-term alliances with the most extreme parties in Italy, political scientist Giovanni Orsina, an expert on Berlusconi and Forza Italia, believes that the party will continue to exist. “It’ll have a different role, of course. Nowadays, it’s the moderate and minority wing of a majority government. [Forza Italia] is linked to the EPP, with the capacity to act as a bridge between Meloni and the European mainstream. We’re talking about 6% or 7% support.” The result of the next European elections, set to be held in June of this year, will mark its future, which is mainly based in southern Italy.

Berlusconi’s legacy, Orsina believes, is rather sociological. “It’s the right-wing electorate, which he knew how to [capture] first. He partly discovered it and partly invented it. It existed, but he gave it shape. And today, after the [brief government] of the Five Star Movement, which broke the balance of power, [the right-wing] once again represents that 45% or 47% of Berlusconi’s initial era. But [most of the vote] is in the hands of other parties.”

Orsina points out that Berlusconi “contributed innovation in communication, in the relationship between leadership and the mass media. But these are methodological things, not related to content. [Policy] was closely linked to the period in which [the party] appeared, to the optimism of the 1990s; the emphasis was on the market, on civil society. It was a state of mind, a dream. The idea that the future would be better than the present. Berlusconi was able to condense this decade. And very little of that remains.”

Of the founders of that political party, few are still on the scene. Perhaps just Gianni Letta, Berlusconi’s old chief-of-staff and Rasputin-in-chief, or Fedele Confalonieri, his partner on cruise lines, who is currently the president of Mediaset, an Italian mass media company.

Berlusconi was the first great populist. He was also a pioneer in talking about ideas such as “the old politics” and creating a system without apparent intermediaries between him and the voters. This was something that parties based on “participatory democracy” such as the Five Star Movement benefited from two decades later. But he was also the man who opened the door of the political institutions to the far right in post-war Italy. It happened long before this issue was talked about in Europe.

Historians and political scientists identify November 18, 2007 as the moment when this occurred. That was when “the knight” (Berlusconi’s nickname) got out of a car parked in Piazza San Babila, in Milan, just after six in the afternoon. There, he proclaimed the birth of a new party in Italy: Il Popolo della Libertà (“The People of Freedom”). Thus, he fused the entire spectrum of the right, including the most radical wing emerging from the embers of fascism, such as the National Alliance.

From that moment on, figures from the fringes began to take part in Italian governments, such as Giorgia Meloni, who served as minister of youth between 2008 and 2011. The result of that experiment, together with the eternal leadership of Berlusconi, was that of a father devoured by his children.

Forza Italia is now in the hands of several currents, over which Antonio Tajani presides. He’s perhaps the only founder with a truly active role today. The former president of the European Parliament is responsible for the rapprochement between the party and the far right, an engagement always blessed by the president of the EPP, the German Manfred Weber. “I feel the spirit of 1994,” Tajani has said in recent days, alluding to the vigor of a past era, in an attempt to refound a dwindling party. In part, the original sin lies with Berlusconi, who never wanted to clearly name a successor.

Thirty years later, what remains of that world met at the Fountains Hall in EUR, a residential and business district in Rome, Italy. The event was presented by journalist Bruno Vespa, host of the historic TV program Porta a Porta (“door-to-door”). Back in 2001, he made his set available to Berlusconi, who signed his famous Contract with the Italians on live TV.

At the meeting on Friday, Azzurra Libertà, the party anthem, was played. Many of those present were excited. It was the perfect time to see how the famous nine-minute-long video that announced one of the biggest political changes in Europe during the second-half of the century has aged.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.