Israel is open to a ‘reformed’ Palestinian Authority governing Gaza after the war ends

A senior Israeli government official has called on leaders from the PA to educate the new generations ‘in the values of moderation and tolerance without inciting violence.’ The U.S. and EU are pushing Netanyahu toward a two-state solution

“I will not allow us to replace Hamastan with Fatahstan,” Prime Minister of Israel Benjamin Netanyahu said on December 16. He was expressing his radical opposition to the Palestinian Authority (PA) — governed by Fatah — taking over the Gaza Strip, now controlled by Hamas, after a military operation that has already caused 20,000 deaths (70% of whom were civilians). The statement in which Netanyahu asserted his position came following his first acknowledgment of disagreements with the United States on the post-conflict scenario in the Gaza Strip. In so doing, he was also rejecting the two-state solution that has been resurrected by Washington and the European Union. “I will not allow the State of Israel to repeat the fateful mistake of Oslo,” he said, referring to the 1993 accords that created the PA and made such a solution possible. Five days later, however, the head of Israel’s Security Council has opened up to the possibility of the PA governing the Gaza Strip but calls for its deradicalization.

Netanyahu’s initial unwavering position seems to be cracking among the prime minister’s aides. “Israel is aware of the desire of the international community and the countries of the region to integrate the PA [in Gaza] when Hamas disappears,” the chairman of Israel’s National Security Council, Tzachi Hanegbi, wrote in an article published Thursday in the Saudi digital media outlet Elaph. “The matter will require a fundamental reform of the PA that will focus on its duty to educate the new generations in Gaza, Ramallah, Jenin and Jericho [the latter three are West Bank towns currently controlled by the PA] in the values of moderation and tolerance without inciting violence against Israel.” Hanegbi’s article noted that achieving that goal “will require great effort and assistance from the international community.” The article concluded that “we are ready for that effort.”

The Israeli government denies that there are any contradictions between the stance Hanegbi’s article expresses and Netanyahu’s position. “What Israel wants is a moderate Palestinian administration with the help of moderate countries,” a senior official in Netanyahu’s government explains. “We don’t want Hamas, nor do we want a repeat of the present situation with the current PA, nor do we want to be the ones to rule the Gaza Strip.” According to this senior official, Israel’s objectives in the war in Gaza are to demilitarize and de-radicalize it, but also to “establish a civilian administration that cares about the people who live there.” In its vision of the post-conflict scenario, the prime minister wants to count on the cooperation of “moderate countries,” such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, as well as the United States and the European Union.

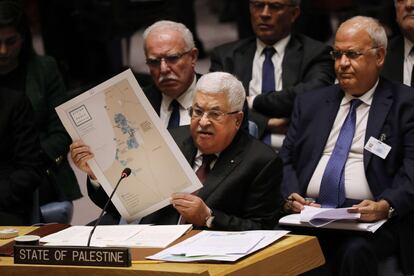

“We need new [Palestinian] leadership. People who don’t hate us,” this senior official maintains. He says that a change at the top of the PA is necessary because the government of Mahmoud Abbas “doesn’t want to participate in this vision of reconciliation and doesn’t want to be our partner.” The official adds that “we tell them where the terrorists are in the West Bank, and they do nothing. The PA is educating their children to become murderers; they talk to them about terrorists as martyrs to be admired,” he continues. The senior official argues that the “deradicalization” that Israel seeks is not going to be achieved in the administration’s current configuration. They want a change. “I hope we get it.”

But the Netanyahu government’s timid path toward possibilities is not only reflected in its openness to hypothetical Palestinian control of the Gaza Strip but also in a new pause in the fighting that would allow another exchange of hostages for Palestinians imprisoned in Israeli jails. After his radical refusal to negotiate a new truce, the Israeli prime minister was forced to do so amid domestic pressure for the release of the hostages, following the incident in which three hostages waving white flags as a sign of surrender were shot by the soldiers sent to rescue them; they mistook the hostages for Hamas fighters.

Israel wants to reach a new agreement with Hamas to free the hostages and has taken steps to do so. This week it sent David Barena, the director of Mossad (Israel’s foreign intelligence service), to meet with the Qatari government, which, along with Egypt, is acting as an intermediary. To achieve this exchange, Hamas demands an immediate cessation of hostilities, which the Israeli government is not willing to concede. Sources from Benjamin Netanyahu’s office say that the process is at a standstill and that “there is no negotiation” for the moment. But these same sources note that Israel is open to a new agreement to free all the hostages, “the sooner the better.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.