Mass exodus from the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan: Two stories of flight from Nagorno-Karabakh

The clash between the two countries has forced over 100,000 ethnic Armenians to flee their homes

Over 100,000 ethnic Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh were forced to flee their homes last September, following the rapidly escalating conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over control of this Caucasus region. After three decades of hostilities that have left some 40,000 people dead, the authorities of the self-proclaimed republic agreed to dissolve its government and armed forces. That decision was made 24 hours after the start of Azerbaijan’s bombing of Nagorno Karabakh when they realized that they did not have any international support.

Most of the population of Nagorno Karabakh moved to the Armenian border province of Syunik. It was a long and exhausting journey, especially since the military offensive was preceded by a nine-month blockade of the Lachin corridor, during which virtually no supplies or humanitarian aid entered, leaving many families without resources. There was only one way out of Nagorno Karabakh: a winding mountain road. After three days of travel by car with very little food and water, the mass exodus exacerbated diseases and caused malnutrition; some even had to make the trek on foot.

“These refugees had nothing when they arrived,” explains Marcella Maxfield, Action Against Hunger’s Regional Director for the South Caucasus. “Facing an uncertain future, they now desperately need emergency aid, both for urgent needs such as food and water, and for necessities like bedding, medicine, mental health care and psychosocial support.”

Below are two stories of the exodus from Nagorno Karabakh.

Nora

On September 25, Nora —who does not want to reveal her identity— fled the conflict with her entire family: her grandmother, aunt, niece, newborn cousin, mother, father, husband, sisters and brother. Three days later, they arrived in Goris, Armenia. On the last two days of the journey, they had nothing to eat. They were forced to drink water from lakes and rivers in the surrounding mountains. “We couldn’t even sleep for an hour,” Nora says.

During the blockade, Nora was pregnant, but she miscarried due to acute stress and malnutrition. Access to health services was limited and it took more than an hour and a half to walk to work. They relied mainly on the potatoes they grew themselves. She now lives with some of her family in a town called Parakar in Armenia. Their apartment lacks electricity, gas and water. They have a small amount of savings to buy food, but it is already running low. Nora is especially worried about her seven-year-old brother. “He needs psychological support,” she says. “He can’t sleep because he still hears the bombing.”

Nora has only one wish: to return home. “I want to go back to Nagorno Karabakh,” she says.

In the image on the left, Nora’s younger sister poses in her current apartment in Parakar, Armenia, to show a photograph she took before fleeing. It shows the bread the family baked to take with them on their way to Syunik, the Armenian province closest to the border crossing. The journey took three days, but there was only enough bread to eat on the first day. They also brought medicine for their grandmother. In the picture on the right, the cell phone photo shows their last meal, a few boiled potatoes the family prepared before leaving Nagorno-Karabakh.

In the picture on the left, Nora’s younger sister shows a photograph she took after the September 2023 bombings. She explains that, before fleeing to Armenia, one of her relatives threw away a cupboard full of cans of food out of anger over the conflict and being forced to flee. In the image on the right, the photograph on the cell phone shows the moment when the family bolted the door of their apartment in Nagorno Karabakh just before fleeing to Armenia.

In the picture on the left, Nora’s younger sister shows the family’s garden in their apartment in Nagorno Karabakh. The image on the right shows a photograph she took with her cell phone during the nine-month blockade of Lachin. The image shows two neighbors riding the horse that Nora’s family also used to travel to health centers 20 to 40 kilometers (12.4 to 25 miles) away. Many families had to travel on foot or on horseback because of the lack of fuel due to the blockade of the corridor.

In the image on the left, Nora poses in her bedroom in Parakar. The image on the right shows the stove with which Nora’s family cooks their food, as they have no electricity.

Armine and Sasun

Armine and Sasun, 44, who prefer to remain anonymous, have supported each other for over two decades. They knew each other in childhood. They grew up as neighbors and even went to the same kindergarten. They have been together for 23 years and have a son and a daughter.

In 2009, they met a woman living in the Armenian town of Goris, and over the years they forged a close friendship with her. She was the one who offered them a house when the family was forced to flee Nagorno Karabakh on September 26. The apartment where they lived was destroyed.

In the months prior to the conflict, Armine and Sasun had already been living on meager food rations as a result of the blockade of the Lachin corridor. The authorities gave them vouchers to buy food, but the quantities were barely sufficient: three kilos of vegetables, two kilos of fruit, two kilos of potatoes and a small amount of bread. Armine and Sasun had to divide this ration among the whole family. If they didn’t use the vouchers to buy food within two weeks, they lost the opportunity, and there was no telling when the next batch of vouchers would arrive. Buying food was very expensive: a single cabbage could cost around €15 euros ($16.35).

Armine explains that they took care of “each other.” She says that her son once went to the nearest bakery, several kilometers away, and had to wait in line until five in the morning. On the way home, he gave the bread to a disabled man he encountered who was in a very bad way.

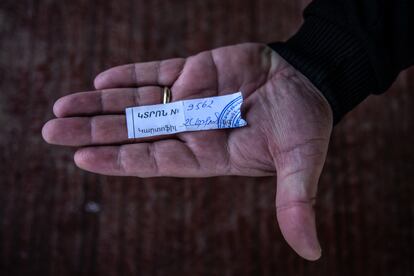

In the picture on the left, Sasun holds the pink ration card they were given in Nagorno Karabakh with which they were allowed to buy two kilos of fruit between February 23 and March 7. Armine and Sasun explain that a cabbage costs about 6,500 drams (about €15/$16.35) and an egg cost 1,000 drams (about €3/ $3.27). All four members of the family (Armine, Sasun, their son and daughter) were working, but Sasun explains that they saw many others starving: “People helped each other as much as possible, but we saw many cases of pregnant women who lost their babies due to malnutrition,” Armine adds. In the picture on the right, Sasun holds the green ration card they were given in Nagorno Karabakh, which allowed them to buy three kilos of vegetables between March 8 and 22.

In the picture on the left, Sasun holds the white ration card they were given in Nagorno Karabakh that allowed them to buy two kilos of potatoes. In the image on the right, Armine holds up her cell phone showing a photograph of the apartment where they lived in Stepanakert, Nagorno Karabakh.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.